The jury, composed of Takashi Yanai, FAIA, Anne Schopf, FAIA, Marc L’Italien, FAIA, Heather Holdridge, Assoc. AIA, and Frank Clementi, FAIA, recognized Brooks as a brilliant designer and a steadfast advocate for the environment on a global scale. A window into her experience and convictions can be found in the following excerpts from Ordinary and Extraordinary, Tibby Rothman’s brilliant narrative of the Brooks + Scarpa practice.

MORE “BERKELEY” THAN SCI-ARC

Between completing her bachelor’s degree and arriving at SCI-Arc for graduate study, Brooks worked for the Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP San Francisco office. She had sought the position because it was an opportunity to be a part of the design team on city buildings at a large scale, a venue to channel her early interests in urban design.

She liked the work, but when Brooks returned to school, she also returned to what had driven her to architecture in the first place: the big picture.

Her master’s thesis was not on an architect or materials: it began as a planning study called “Post-Suburbia.” When Brooks traveled to the outliers of Los Angeles, driving by vast expanses of checkerboarded single-family homes and garages, she confirmed an instinct. People did not use the ancillary structures as intended by city planners and officials.

Thousands and thousands of garage square feet and the resources voraciously eaten up to construct them were repurposed as storage space or gyms. Vehicles were left on streets.

SCI-Arc was known for its exploration of avant-garde form making. Other students dubbed Brooks’ thesis more Berkeley, the university interested in policy issues, than SCI-Arc: her advisor said—run with it. Expand your photographic essay and document the data. For six months she did, walking the streets of El Segundo, asking strangers if she could take pictures of their garages, living rooms, yards.

Then Brooks developed prototypes to supersede the 1960s planning policies that had led to miles of suburbia, acres of bedrooms disassociated from retail and other services.

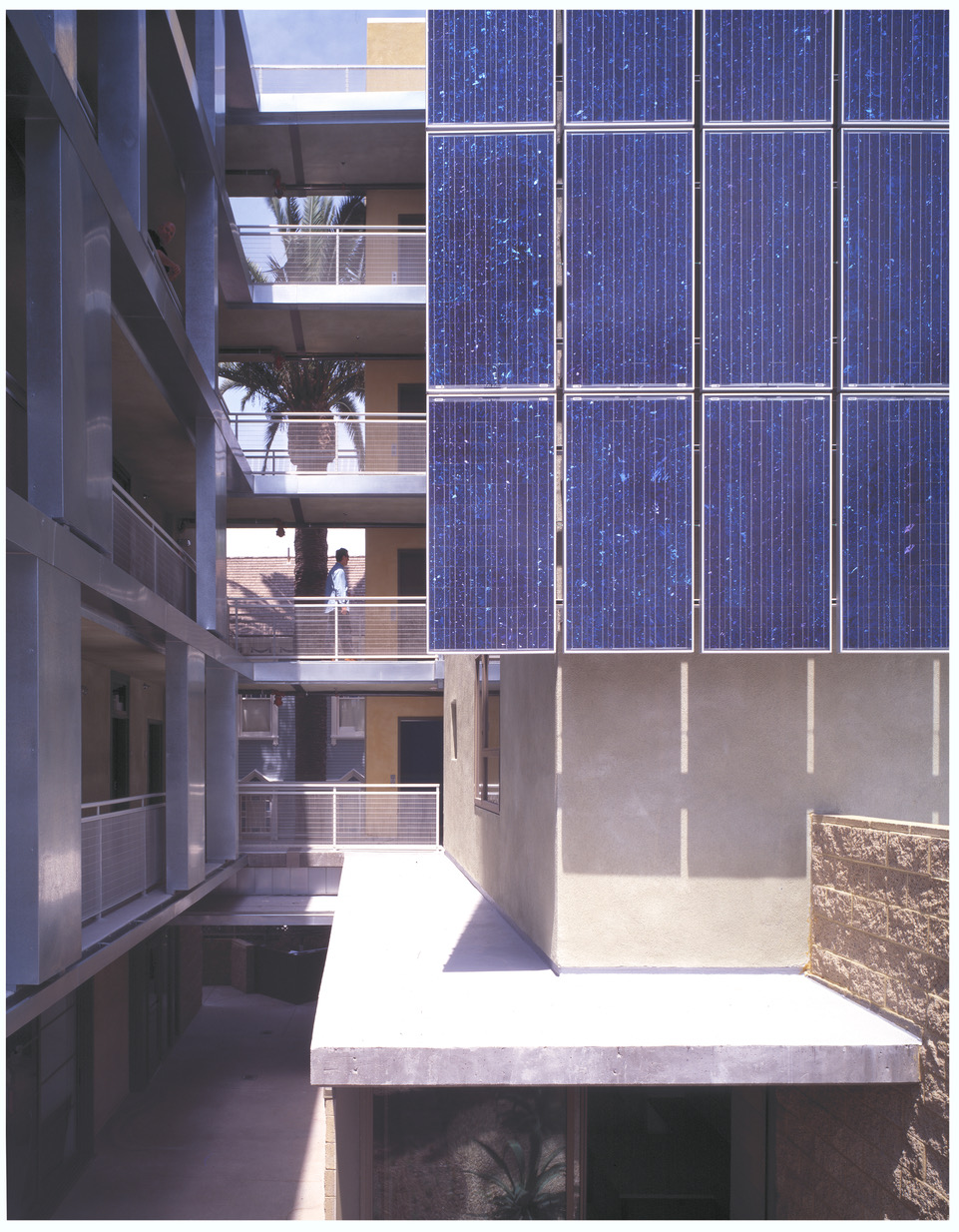

It was 1988. The AIA Committee on the Environment (COTE) would be launched the next year, but Los Angeles’ infatuation with smart growth was still more than a decade off. The ideas Brooks proposed were prescient: housing above shops at busy corners; lots tied together in order to share amenities such as barbecues and laundromats and storage; forms that reflected the Sarasota movement—housing on stilts—but with new programs: parking in unused space below, multi-family housing versus single units, gardens on roofs, light wells to draw the sun from the sky to the ground floor. Page by page, Brooks laid out a precise, detailed plan to build on, combine and replace suburbia with microcommunities.

CITIZEN ARCHITECT

For decades, Americans identified housing for people on low incomes as isolationist superblocks, places of abject failure. In New York, the Marcy Projects. In Chicago, Stateway Gardens. In Amsterdam. the Bijlmer. But by the 1990s, this approach was outmoded thinking. Affordable housing had a new energy. The emphasis was “community.”

Models for affordable housing began to address a number of the conditions Brooks was interested in: de-suburbanize, don’t waste land, link amenities to residential. Though these individual developments could not change a city in its entirety, they began to establish beachheads.

Housing providers had also recognized that having a stable place to sleep is only a baseline: more is required for upward mobility, or even stasis. They began to offer clients support services located within their apartment buildings.

In one of her first postgraduate positions, at the Los Angeles Community Design Center, an affordable housing developer, Brooks would be part of that change. “It was the only way I could make an income and do what I wanted to do,” she says. What she wanted was to take on the role of the developer, to build better urbanism, to expand the percentage of the population that experienced good design.

WHAT WE BELIEVE

Work on the micro and the macro. We can’t always change ‘big picture,’ but we can arrange a view for a teenager at a Green Dot school.

Micro is macro.

The practice of architecture is to pay attention.

Consider the long term. Building is resource-intensive. Land is precious, materials are precious, time is precious, creative resources are precious. Conserve, recycle, sustain; give each resource multiple functionalities. Construct buildings for century-long lifetimes. (A reminder from our friend Katie Swenson.)

Support people. Make their lives healthier, more beautiful, better.

When the lives of a city’s most vulnerable residents flourish, we all flourish.

How do cities develop over time? That’s something we’re Interested in.

See different perspectives. (We’re designing a streetscape for a coastal city, right now—what will it look like, what is its meaning from a boat?)

Collaborate with your competitors. (There are no competitors. Just ideas.)

Challenge is innovation. Do firsts.

Every commission is discovery. A park bench, a piece of furniture, a museum, a parking lot. Scale changes, discovery remains. Discovery is big.

Design is not what a building looks like, but what a building is. A building is experience.

Creativity is a democratic process. Be smart: work with smarter, more creative, more talented people than you. There’s always someone with the best idea in the room.

Our buildings have no authorship. Their stories begin before we arrive on site, and continue with those who move through them.

When Larry suggested a small pool of water to a client for their home, what he was thinking about was: its reflections on a ceiling. Architecture isn’t still. Architecture changes.

Architecture is discovery.

From arcCA DIGEST Season 07, “Concerning California.”