Friends of mine whose children express interest in going to architecture school point them toward me for advice. They assume I will say inspiring things and help their children choose that path. After all, I’ve been in the design business for 35 years and a licensed architect for most of that time, plus I teach an architecture design studio at the university level. But even with all of that, I hesitate with my career recommendations for a moment, choosing my words very carefully when advising young people.

It is a great profession, and it has been a good fit for me. I was drawn to the combination of artistry and logic – sketching and geometry, freedom and rules, and the opportunity to navigate between them, somewhat like a jazz musician. It also gave me a sense of control and mastery, which was something I craved. But eventually with that came a lot of responsibility. I may have made it worse by choosing to go into business for myself very early in my career. Again the freedom, but it came with plenty of worries. I remember my son saying to me, after I was up half the night working on a project, that he wanted to find a job with as much independence and freedom as I had, but without staying up all night, and for a big company that would write him a paycheck every week, no matter what. He did not choose architecture.

The author Kurt Vonnegut Jr. captures this conundrum with humor and appreciation. In a 1969 letter to his son, he relayed the advice that his own father gave him years before, “Never take liquor into the bedroom. Don’t stick anything in your ears. Be anything but an architect.” (Which both his father and grandfather had been). However, decades later in a letter to a high school class he wrote, “Practice any art, music, singing, dancing, acting, drawing, painting, sculpting, poetry, fiction, essays, reportage, no matter how well or badly, not to get money and fame, but to experience ‘becoming,’ to find out what’s inside you, to make your soul grow.” What he should have added is that it’s worth staying up late to do this. Most architects will tell you that the flow state and the insight they achieve when working long hours and solving problems is deeply satisfying and meditative, like an athlete who enters ‘the zone’ when they exert themselves beyond their usual limits.

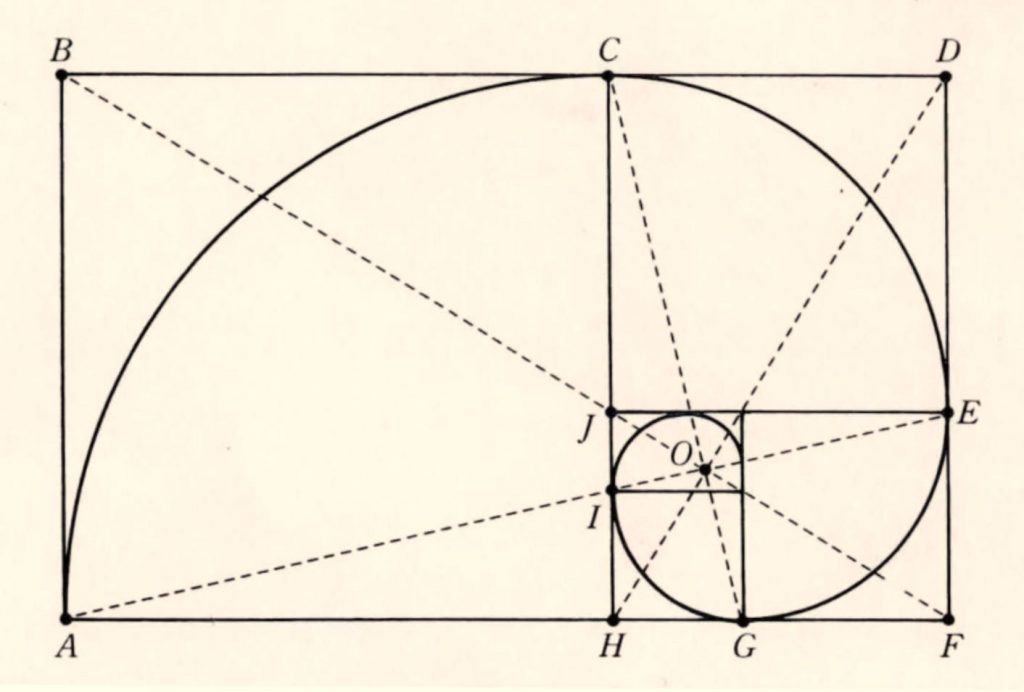

I knew I wanted to be an architect from about 12 years old. My mother was an interior designer and I spent hours playing with the drawing tools on her sloped table top with the Luxo lamp clamped to the edge (the ubiquitous drafting lamp memorialized by Pixar in their animated logo). In college I would buy my own drafting table. It was a right of passage. I still have it, though there is no longer a T-square or a Mayline straightedge attached to it. It’s just a desk now, with a laptop on it. Most of the other drawing tools have also drifted away, into drawers, boxes, and garage sales. Compasses, French curves, ink pens, Zipatone pattern sheets, and pencils of every flavor and density. In my first design class I was assigned a drawing exercise, which had to incorporate various media and colors, to test how they all printed on the diazo machine – the ammonia based “blueprint” process that was not always blue. It also had to be a compelling creation unto itself. Drawing used to be a craft. It was more tactile and personalized before computers.

We have traded much of that craftsmanship for the power of CAD modeling and hyper-accurate rendering. Older architects lament the demise of hand drawing constantly, especially as younger people enter the field who are more comfortable with computers and software than with pen and paper. It’s a little like when Bob Dylan switched to electric guitar and some fans insisted that he lost his authenticity. But the times were indeed changing. Technology pushes the tools of art forward just as it does most other things. Personally, I like design technology, because it offers me the ability to sculpt a 3D model in real time, visualize options immediately and edit cleanly. However, I first learned to think in three dimensions by hand drawing, so I never deny its importance, and I still teach it to my students. The critical point is that our job is to visualize solutions, then convey them effectively to others using every means available. Architect Elizabeth Diller, the only architect named on Time magazine’s list of the 100 most influential people of 2018, puts it this way: “Many tools are indispensable for my work, from a utility knife to parametric modeling software. But it’s important not to confuse the tool for the content.” Or, to push the Bob Dylan analogy further, I remember one of my favorite professors pointing out that Dylan was important because of his message, not the tone of his voice.

Architects commanded respect in the households of my youth, especially when my father and his new wife hired one to design their new home for our blended family. That architect attained godlike status in our home. He created a house from thin air and casual conversations with all of us. He taped pencil sketches on yellow trace paper to our dining room wall for a family meeting – schemes A, B, and C, the time-tested format. He brought to life the monument my father wanted to build to his new family. It was published in a magazine. It was a big deal. My social cred increased because I lived in a really cool house. The architect became the subject of legendary stories around our dinner table. There was the cantilevered deck in the trees that provided a bit of structural magic, or the clerestories that filled the spaces with natural light even on a gray rainy day. And there was the time he showed up for a construction site visit and quickly spotted a single brick out of plane in the two-story chimney made of hundreds. He was creative and exacting. He had “the eye.” He even picked our furniture. Our family wouldn’t last and the monument was sold right before the foreclosure started, but my impression of the architect’s power endured. I had seen something transformative, and I wanted to pursue it.

Our builder was also a somewhat mythic figure in the process. He and his crew wrestled the crude materials into their designated arrangements. The job site was loud and chaotic, but the results were harmonious and balanced. Talk about creating something out of thin air. This was much bigger than the drawings. He was also the manager of the costs. His operation ran on money, and it commanded allegiance. The most money I had ever seen was the envelope fat with $100 bills that my father brought home once, to pay the builder under the table for some extras. That was another lesson about power.

Given all that, it’s not surprising that my own path into the architecture profession passed through construction. As a student putting myself through architecture school, I remembered that envelope full of cash. So I found my way into construction, first as a laborer, then as a carpenter, and later as a design-build contractor, merging the design and construction businesses. I worked for an architect, as well, but I preferred cutting and fitting wood to sitting at a drafting table revising plans, which consisted mostly of erasing carefully against the edge of a metal shield, then imitating the line weights and lettering styles of others who preceded me. The better I was at my drafting job, the more I disappeared into the drawing sheet. Conversely, building made me feel like I was leaving my mark on the world every day.

Fifteen years in the trades taught me something else, though, which I pass along to young people who want to become architects but are tempted by construction. The construction business is essential to learn, but for me at least, it was ultimately not as fulfilling as design. Design is less mechanical, more complex and emotionally richer. It is considered a profession rather than a manufacturing trade. It is also a right brain activity, in the realm of the arts. Architecture is rooted in materials and building processes, but it grows upward, toward the lofty heights of the imagination. That is where the blossoms occur. As a junior draftsman, I did not realize this, but, as my experience broadened, the possibilities to make that creative mark on the world increased exponentially as an architect. I am reminded of a quotation from the songwriter Bruce Springsteen’s biography, “The need to transform yourself drives the artist.” That need drove me to leave construction behind, so that I could pursue architecture full time. I have never regretted it and I am now able to leverage my imagination and my problem solving abilities far beyond what I could lift or nail together.

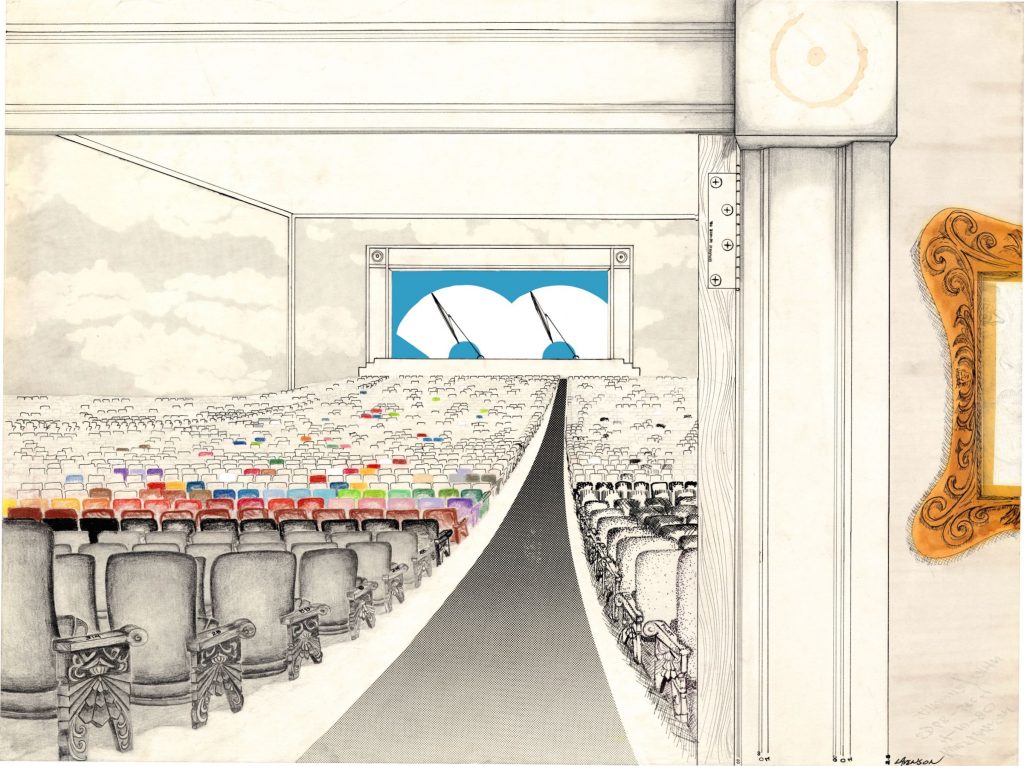

The turning point was after I completed my first whole house project as both the builder and the architect. On the way to see it, my father in law, who was a practical guy, asked me about the square footage, the cost, how long it took to build, those sorts of things. When he walked into the living room, he ran his eyes up the brick chimney and across the timbered ceiling, folded his arms, and fell silent. His face changed, and I saw vulnerability. He was moved. He let out a long breath and said, “I’m proud of you son.” From him, a man of few words, that was a high compliment. I knew he understood and appreciated the construction work and the care that was evident, but I could tell it was the feeling of the place that opened him up. It was the architecture. Le Corbusier, one of our greatest modern era architects, said, “The purpose of construction is to make things hold together; of architecture to move us.”

So, when advising young people considering the profession, I explore their deeper artistic motivations. Are they ready to search extensively for the best results and fundamental transformation? Are they driven to move people’s emotions and to pursue their own “becoming?” If so, then this is a rewarding path. If they are just interested in surfaces and the latest styles, they might still do fine, but they will not soar. The weight of architecture will be too much. They might be happier in web design, graphic design, or animation, maybe even sales and marketing. Architectural problems are about the complex underlying order of things. The satisfaction of resolving those puzzles is hard won. It is ultimately about light, space, form, function, and delight. Beauty derives from their successful integration with one another. The design process is filled with sticky problems that are not easily solved, or that can be solved in a multitude of ways, but few of them are elegant and long lasting. The artist and architect of the Vietnam Memorial, Maya Lin, says, “In art or architecture your project is only done when you say it’s done. If you want to rip it apart at the eleventh hour and start all over again, you never finish. I was one of those crazy creatures.”

As an architect you spend your time discovering, evaluating, and refining options. It is thrilling to develop a well-woven design that “solves the problem” and feels inspiring. As you learn more and get better at the work, you often realize that you could have done something different and even better, but with fewer moves. You keep practicing. Your friends call you picky. The blank page torments you. You love what you have created, yet you still want to rip it apart and do it over. It is torture and it is ecstasy.

This article is the third in a series of reflections on architectural practice by Kurt Lavenson. The previous two are “In Praise of Fallow Fields” and “Well Designed Struggles.”

From arcCA DIGEST Season 5, “Motivation.”