The urban services that we so often take for granted comprise the most ubiquitous of design challenges. They form, in large part, the basis for the public realm, the place of our encounter with each other, with our predecessors and with the collective values and aspirations of society. The streets, bridges, transit systems, service centers and institutions that are created in the public interest by government action and regulation set the terms within which our individual creative action and experience take place.

The realm of public design can be a forum for leadership at all levels of government, from federal programs to local, neighborhood organizations. In many great periods it has been. Much of the history of monumental architecture is written about buildings of the public realm, and the history of the vernacular environment is suffused with the underlying structures of public rights-of-way and services.

Facilities created for the public can and should embody qualities of concern for human experience and for the equitable and purposeful use of resources. If well designed, they can set standards for private enterprise, and the infrastructure created by roads, services and regulation can evoke the creative involvement of entrepreneurs and engineers in shaping the environment we share.

We should come to think of all design projects as infrastructure— setting the stage for use and elaboration by others. It is not just the shape of what is built that matters, but what it can make possible in use and in subsequent attraction and adjustments.

This is especially true for the design of the public realm, which is made palpable not only with grand projects but also with every step underfoot, with the organization of paving and planting of rights of way; the curbs, sidewalks, roadways, trees, tree gratings, drainage systems, signage and lighting. All these are often relegated to the realm of public works engineering and discarded from conscious design thought. They form, though, the substructure for our actions, they determine how smoothly we move on foot or in vehicles, how easily we exchange with our neighbors or gather in public assembly, how gracefully the forms of our surroundings are fit together and how they reflect our values.

Architecture in the public realm spans across a range of scales, from the shape and material of a curb to soaring structures that shelter places of public assembly; from objects and spaces that are everywhere in our lives to great monuments that mark moments of collective memory. Both the fine-grained and the colossal present opportunities for caring to get it right—to show that shrewd and persistent imagining, when coupled with attention to the multiple interest, can make places that carry our interests, hopes and pleasures into an evolving future.

Author Donlyn Lyndon, FAIA,is Eva Li Professor of Architecture and Urban Design, Emeritus, at UC Berkeley and one of the founding editors of PLACES, Forum of Design for the Public Realm. He is a recipient of the AIA/ACSA Topaz award and the AIACC Lifetime Achievement Award. Lyndon’s writings, buildings, and teaching have explored ways that architecture can relate to the places of which it is a part and enhance the lives of those who live there. This article is reprinted from Places, vol. 9, no. 2, by permission.

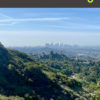

Photo collage by Ragina Johnson.

Originally published 4th quarter 2009 in arcCA 09.4, “Infrastructure.”