Over the past few years, the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission has become increasingly concerned that continued sea level rise from global warming will have profound impacts in the San Francisco Bay region, largely because over 200 square miles of low-lying, filled land borders the Bay. Because BCDC was created largely to regulate Bay fill projects with the goal of preventing the Bay from becoming even smaller from unnecessary landfill projects, BCDC was not legally responsible for dealing with this dramatic change that is making the Bay larger. Nor did BCDC have any explicit legal authority to address this problem. In light of this situation, the Commission requested that the staff provide a broad outline of a comprehensive strategy for addressing the consequences of climate change in the Bay region and identify any changes that would be needed in state law so that BCDC can play a productive role in implementing such a strategy. The text published here is drawn from that report.

“The world we have created today, as a result of our thinking thus far, has problems that cannot be solved by thinking the way we thought when we created them.” – Albert Einstein

Background

San Francisco Bay is the largest estuary on the west coast of the North and South American continents. When the California Gold Rush began in 1849, the open waters and bordering wetlands of the Bay covered 787 square miles, and this magnificent natural harbor teemed with wildlife. But the Bay was shallow, two-thirds of it less than 12 feet deep. The unfortunate result was that as the new State of California began to grow, the Bay began to shrink. Shallow tidal areas were diked off to create salt ponds, farmland, and duck hunting clubs. Municipalities used the Bay for garbage dumps. Siltation from hydraulic gold mining in the Sierra foothills washed into the Bay and filled wetlands. And numerous land reclamation operations were undertaken to create dry real estate where Bay waters once flowed.

By the middle of the 20th century, the Bay’s open waters had been reduced to 548 square miles and nearly a third of the Bay––239 square miles––was gone. In 1959, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers published a report that concluded that it was economically feasible to reclaim another 325 square miles––60 percent of the remaining Bay––by 2020. The Bay Area public rejected that notion and, in 1965, Bay Area citizens convinced the California Legislature to establish a new state agency––the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC)––empowered to regulate new development in the Bay and along its shoreline so that any future fill placed in the Bay would be largely limited to water-oriented uses that could not be accommodated on existing land.

BCDC has been highly effective in achieving this public policy goal. By limiting the use and size of new landfills and requiring mitigation in the form of wetland creation, BCDC has reversed the shrinkage of the Bay; it is now nearly 19 square miles larger than it was in 1965. With BCDC’s support, 26,000 acres of privately owned salt ponds have been purchased by the public to improve their habitat value and convert some of the ponds to intertidal wetlands, resulting in a further expansion of the Bay.

One of the most publicized impacts of global warming is a predicted acceleration of sea level rise. This acceleration would increase the historic rate of sea level rise, which has been measured in San Francisco Bay for over 140 years. Between 1900 and 2000, the level of the Bay increased by seven inches. Depending on which end of the range of projected temperature increases comes about, water levels in San Francisco Bay could rise an additional five inches to three feet by the end of this century. More recent analyses indicate that sea level rise from warming oceans may be 1.4 meters (about 55 inches) over the next 100 years, or even higher depending upon the rate at which glaciers and other ice sheets on land melt.

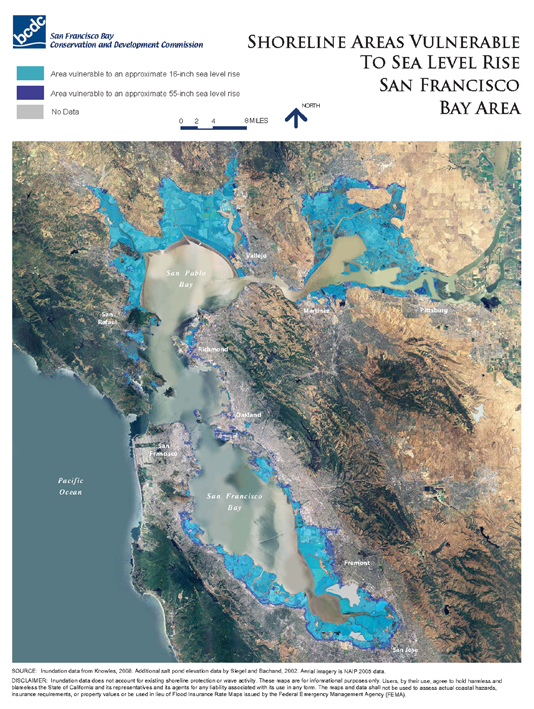

Using GIS data, BCDC has prepared illustrative maps showing that a one-meter rise in the level of the Bay could flood over 200 square miles of land and development around the Bay. Initial estimates indicate that over $100 billion worth of public and private development could be at risk.

Impacts from sea level rise are most likely to occur in concert with other forces that already contribute to coastal flooding. When superimposed on higher sea levels, these conditions will create short-term, extremely high water levels that can inflict damage to areas not previously at risk. For example, computer models indicate that a one-foot rise in sea level will increase the likelihood that the most extreme storm surge event, which now occurs once a century, will occur once every ten years.

Meeting the Challenge with a New Type of Bay Plan

A bold, new plan for the Bay is needed to meet the challenges of sea level rise head-on. The goal of the plan should not be to restore the Bay to historic conditions, because climate-induced changes will not allow it. Instead, the plan should be a vision for resilient communities and adaptable natural areas around a dynamic and changing Bay that will have different sea level elevations, salinity levels, species and chemistry than the Bay has today. A new pattern of development will be needed to respond to these changing conditions. Because the rate of sea level rise and other impacts of climate change are still uncertain, the plan should embrace a pro-active, adaptive management strategy that can respond to future changes.

The new plan should rely on ecosystem-based, adaptive management principles to ensure that future development, shoreline retreat, flood protection and habitat enhancement strategies are coordinated to achieve a vibrant, healthy Bay co-existing with sustainable communities along the shoreline.

The first step in preparing this plan should be to determine more precisely which shoreline areas are vulnerable to flooding and storm surge from sea level rise. With this information in hand, the value of both built and natural resources that will be impacted can be determined. Next, the flood-prone areas that are already occupied by development that is too valuable not to protect should be identified. Using this information, a regional flood protection strategy can be prepared to describe all the dikes, levees and other protective devices that need to be built.

The next areas that should be identified are: flood-prone areas where it may be more cost-effective to remove existing development than to protect low economic value structures; low-lying areas that are planned for development that has not yet been built where it may be more cost-effective to abandon these plans than to try to protect the new development from flooding; and undeveloped upland areas where marshes can migrate when sea levels rise. Making these choices will be difficult, particularly if the areas contain significant environmental, aesthetic, social, cultural or historic resources or where the removal would raise environmental justice issues.

Another probable impact of climate change is that more precipitation in the Sierra Nevada will fall as rain rather than snow, and the snow pack will melt earlier in the spring. In turn, this will reduce late spring and summer runoff into the Delta, allowing salt water to extend farther into the Delta than it does now. Sea level rise and higher flood flows resulting from climate change, as well as earthquake risk, will also increase the probability of catastrophic levee failure. These conditions could result in the Delta becoming a more estuarine ecosystem. Therefore, the Bay Area’s planning should be closely coordinated with the planning for the Delta.

Tidal wetlands must play a key role in any regional climate change strategy because they are adaptive to climate change by buffering shorelines from storm surge, and they help mitigate the impacts of climate change by sequestering carbon. Hundreds of millions of dollars have already been invested in wetland restoration projects in the Bay Area, and billions of dollars of more investments in habitat enhancements are planned.

Inundation of tidal marshes would be devastating to the San Francisco Bay ecosystem, and the extent and location of wetlands and other habitats likely will shift as a result climate change. However, there is limited space along the shoreline available for marsh migration. Much of the shoreline is either developed or migration is precluded by topography. Pulling existing development back from the Bay’s shoreline and foregoing planned development of low-lying areas can provide an opportunity to build on past investments and allow for migration of tidal wetlands. Therefore, development of upland areas that are suitable for marsh migration could pose a long-term threat to ecological sustainability in the Bay.

This new plan for the Bay should be prepared by a partnership of government agencies that takes full advantage of the unique strengths, expertise and experiences of BCDC, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) and the Bay Area Air Quality Management District (BAAQMD), in cooperation with federal and state agencies, local governments, the business community, academic institutions, and other organizations, with the Joint Policy Commission (JPC) providing the overarching coordination of the planning process.

“There is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things. Because the innovator has for enemies all those who have done well under the old order of things, and lukewarm defenders in those who may do well under the new.” – Niccolo Machiavelli

Originally published 3rd quarter 2009, in arcCA 09.3, “Beyond LEED.”