My landlady was in her early eighties when, as an architecture student, I rented her downstairs in-law unit. It was perfect synergy. We became close friends and came to look after each other. She participated in my parties, and I listened to her stories about the Maybecks, the Boyntons, and the Lincoln Brigade. My friendship with her inspired my Master of Architecture thesis, “At Home With Growing Old,” and continues to inspire my research and professional work.

Growing old at home is the preferred solution for many who consider anything else as “giving up.” Yet moving at old age, too often dreaded and depressing, has the potential to become a source of renewal by what I will call “carrying home with you.”

Moving to a place where we feel helpless, need care, and have little or no opportunity for personal expression can easily induce a feeling of being homeless, because home not only shelters us but also supports our sense of self and expresses our identity to others. How can we support the dignity of self where institutional concerns battle with the desire for a more personal and humanistic setting?

The Purposeful Home

There is a beauty in the order of a place that has a specific purpose: a craftsman’s workshop, a farmhouse kitchen, even a laundry. This beauty is derived not from the drama of design but from serving a purpose and the order it instills. A home for growing old becomes such a workshop. Its purpose is to give us the opportunity to stay engaged and useful, to enable us to remain part of our community, to give us confidence when our abilities and strengths decline, to let the world come to us, to be able to retreat when tired, and to be recognized as who we are. Many senior residences or assisted living facilities aspire in their mission statement to do these things, but nevertheless one often feels a lack of purpose. All too often, a pretended order based on the look of things supplants a purposeful order generated by actual use.

A purposeful home can derive its order from connectivity to a community. This can be an actual physical connectivity or a spiritual one. My mother’s senior residence in Salzburg, Austria, is in the middle of town. On the first floor is one of the most popular Salzburg Cafés. Residents have a card key that allows them direct access from their lobby into the café, where they can linger, eat cake, and watch activity. As another example, the Quakers have developed senior residences through their non-profit organization, the Kendal Corporation. These homes, in their physical and social design, express the values of their spiritual principles and give another layer of meaning to their community.

Ultimately, though, it is our private space, our room, our apartment and its relation to the building as a whole that has to fulfill the purpose of being the essence of our home.

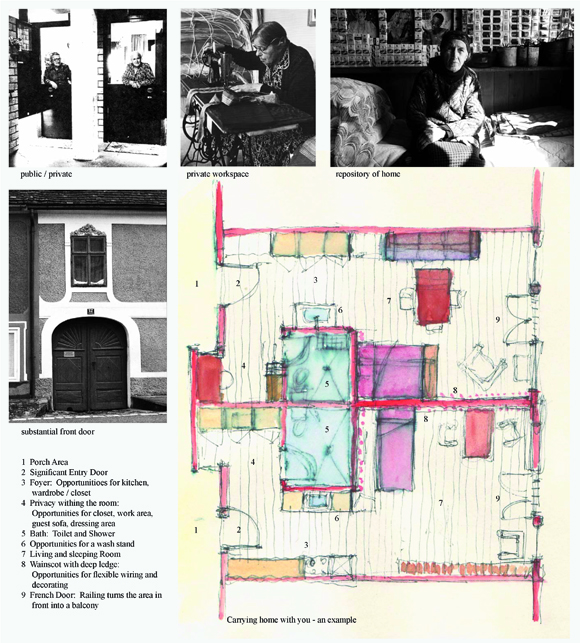

Down Sizing Home—The Room as the Repository of Home

The sense of home comes from a sense of permanence and territoriality supported by the personalization of space and the richness of details and materials. I am currently working on a residential hospice for the Zen Hospice Project in San Francisco. Here, the sense of home is primary, and the challenge is to slip the functions of care giving into the folds of the existing details. Yet in most cases the priorities are reversed: the “design” mandate is to serve the efficiency of care giving and maintenance, rather than the spirit of home.

It is at this time of old age, when change is so physically and mentally part of our daily lives, that we need home most. Our body undergoes changes that affect our spatial experience and independence. We spend more time at home. Our privacy is compromised with the need for assistance in daily living. Often, for financial reasons and ease of maintenance, the size of our home gets much smaller. Home, to retain its power, has to fit like a glove.

This fit can be achieved by designing unique spaces for different needs (a costly endeavor) or by designing uniform spaces with a degree of customization in mind. This personalization of space can embrace such simple decisions as how much kitchen is really needed and the selection of furniture from the old home that will fit the new one. Rooms have to be designed with opportunities in mind. Standard features, such as the bathroom, need a fresh look. The width of an entry area, the placement of a door, all become meaningful in a small space.

When we are old, daily routines gain in importance. For many people, the continuing responsibility for taking care of a home is a meaningful source of independence. It is a matter of pride and is closely connected to taking care of oneself. Design can support independence in performing the tasks of home keeping, such as meal preparation, cleaning, laundry, and personal hygiene. Discovering the right height and organization of built-in storage for easy retrieval of memories or items of daily life can become an important design challenge. A chair rail deep enough to hold mementos and photographs allows for redecorating without help from somebody else. The sink can become a beautiful piece of furniture in the room, accessible without opening a door, giving square footage from the bathroom back to the room.

Spatial strategies need support from material intelligence. Materials should be used true to their characteristics and mindful of what they signify. Where a material is used is important. A material such as plastic laminate, used in the right place for the right reason, is appropriate. Used with a wood print, it speaks of the priority of maintenance only. Investing in home means using materials that fit the purpose of home. A beautiful wood door, for example, says permanence and gives value to whatever is behind it.

The identity of home in these situations arises not from the envelope of the building, but from the definitions of public and private realms and their thresholds. In assisted living situations, this threshold is lower. Spending time with my mother, I became aware that she has lost the ability to invite people to visit, and thus some of her privacy. Friends drop in when they can make time, not when she calls them. Care givers also have a daily routine that does not always coincide with her schedule. Our sense of territory should be indulged to counterbalance the control we lose when we need help. The more strongly somebody can claim a room and the stronger the articulation of the threshold between the outside of the room, the corridor, and the inside, the more it signals privacy and invites a different attitude from visitors. The careful articulation of the entry door can make the corridor seem like an outside space, a space “abroad.”

At Home and Abroad

When we grow old the world must come to us. There should be opportunity for us to go “abroad” into the world without much ado. Many American cities make this difficult, since they often lack density. Yet there are solutions. My favorite one is an ideal building typology that I presented in my thesis, a new mixed-use, civic building type in which libraries, schools, and theatres are combined with housing for the elderly. Imagine the expanded world of the elderly person who has direct access to the San Francisco Public Library, whose kitchen window looks out onto the stacks? The civic component is important. Inhabitants can share in the pride, the identity attached to a civic building. One might have said earlier in life, in a metaphorical way, “I live at the library.” Now, one can say it literally.

There are precedents. At the beginning of the period we call modernism, hospitals, such as the Psychiatric Hospital in Vienna, by Otto Wagner, were designed as buildings of civic pride. And there are contemporary examples, such as St. Jacob’s Park in Basel, by Herzog and deMeuron, combining such functions as a sports arena, shops, and a residence for the elderly. Others mix functions without placing them inside a single building, like the Quaker residence developed by The Kendal Corporation, which has established a close and collegial relationship with nearby Dartmouth University. There is certainly now the potential for an assisted living home to become a standard, civic feature of a neighborhood, as important as the local school or library in keeping people connected across generations.

Home, a Collaboration

Design for functional and emotional needs as we grow old necessitates knowledge and attitudes that go beyond the expertise we typically expect from architects. There is a need for collaboration with other disciplines that serve the same population. An interdisciplinary network of professionals—care giver, psychiatrist, gerontologist, occupational therapist, architect, and lighting designer—can come together to provide for more individualized, nonstandard solutions to our housing needs as we age.

Design solutions for “carrying home with you” are detail oriented, not too complicated to realize, and often unglamorous, but essential to the true spirit of domesticity that defines “home.” They deserve our attention, time, and funds.

Author Susanne Stadler is an architect with creative roots in Salzburg, Austria, where she was born and raised. Her office, Stadler Architecture, is based in Oakland. One of her long-term interests is an integrated approach to design for aging. In her research and design, she continues to explore different models of aging both in the US and Europe.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2009, in arcCA 09.2, “Design for Aging.”