With the stated objective of hiring America’s finest architectural talent to assemble a national portfolio of exemplary buildings, the General Services Administration (GSA) should be considered our country’s most influential architectural patron. Not since the New Deal has the federal government embarked on a deliberate pursuit of excellence in architecture, art, and design. Comparisons to the Medici’s influence on the Renaissance might seem glib, but GSA, like the Medici, ignited a nation’s passion for great works of art and architecture.

In the early 1990s, as GSA was experimenting with initiatives to improve quality, the agency was intensely aware of the legacy it needed to improve. Federal buildings constructed in the 1970s and 1980s were competent, but not uniformly excellent. At the 1992 GSA Design Awards program, new construction projects were nearly shut out. The vast majority of awards went to historic renovation projects. The jury chairman, Eugene Kohn, FAIA, challenged the government to raise institutional expectations for new construction quality. With a looming federal construction boom, the prevailing approach to creating contemporary federal architecture had to change. The architectural elite would not compete for government business unless GSA removed longstanding barriers to competition or, at the very least, rationalized them. The critical ingredients for this change included streamlining the architect selection process and introducing private sector peers to the design review cycle. These initiatives became the foundation of the Federal Design Excellence Program.

Another catalyst for change came from influential members of our nation’s establishment. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan from New York and Federal Judges Stephen Breyer and Douglas Woodlock in Boston pushed the GSA into evaluating public architecture in fundamentally different terms. Breyer and Woodlock wanted their Boston Courthouse to be a gift to the public rather than a fortress for justice. They lobbied for a broader list of architects to interview for the commission and greater inclusion of the private sector in design reviews. Prior to this time, architecture firms were eliminated from competition if they were outside the geographic region of the project. Harry Cobb, architect for the Boston Courthouse, was originally ineligible to compete for the project because his office was in New York.

The challenge of enticing distinguished public buildings from a seemingly unimaginative bureaucracy was daunting. In the 1990s, GSA was better known for buying computers, office supplies, and automobiles than commissioning inspired works of architecture. Remember when Vice President Al Gore smashed an ashtray on the David Letterman Show to symbolize old fashioned government ways of doing business? The ashtray was built to GSA specifications, but why was the government specifying custom ashtrays, when it could purchase them at substantial savings? The Clinton administration sought to reinvent government by challenging conventional wisdom.

The Design Excellence miracle comes from creating our nation’s leading architectural patron in such an unlikely setting. Edward Feiner, FAIA, GSA’s Chief Architect from 1996 to 2005, answered the call of transformation and corralled additional private sector support for his Design Excellence principles. Officially adopted in 1994, the Design Excellence Program was reinforced by the 1962 Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture drafted during the Kennedy administration. These Guiding Principles, apparently dormant for three decades, are as relevant today as they were in 1962. They just needed an interpreter.

Fourteen years later, the once criticized agency maintains the legacy of Design Excellence and carries it into the future. As the new Chief Architect, Les Shepherd, AIA, is empowered to maintain the momentum created by Edward Feiner. Shepherd is an experienced architect and inspired leader who spent a significant portion of his GSA career in San Francisco and Los Angeles. The culture of excellence created by Feiner is now a source of pride for the agency. It is also an expectation of communities that lobby for government projects.

Supporting excellence and innovation, GSA defends architecture against compromising forces of reality, such as construction financing and rigid land-use policies. Construction cost benchmarks are sufficiently scaled to support the performance standards provided to design teams. With a threshold of $10 million or more, Design Excellence projects are also large enough to bear the added expense, if any, of originality. Additionally, federal sovereignty means that project designs are not subject to the mandatory community evaluation process that sometimes creates unwanted compromise.

Evaluating buildings as a 50- or 100-year asset, each project has the potential to be an historic structure, representing American culture at the time of construction. Design reviews to evaluate multiple schematic options are an important step in the process of creating future landmarks. The private sector peers facilitating these reviews are encouraged to critically evaluate proposed designs. Frequently, architects are asked to redesign projects in order to achieve the timeless architectural qualities sought by the government.

The desire to innovate comes as much from GSA as it comes from the private sector. This quest for originality has emphasized environmental stewardship and sustainability since the early days of the program. Although these objectives have public policy underpinnings, the driving force for energy efficiency is life-cycle cost savings. Today, the government understands that being environmentally friendly is also economically sensible.

Sometimes trend-setting, GSA projects are never whimsical. Each project has a client, and that client needs space or modernized facilities. The program does not allow for experimental works of architecture. An aesthetic or functional failure would take decades to correct, but the program supports and encourages innovation. Take, for example, the Sandra Day O’Connor Courthouse in Phoenix, Arizona. The Richard Meier-designed courts building incorporates an adiabatic cooling system for the football-sized interior atrium. Without using conventional air-conditioning systems, the six-story atrium stays twenty to thirty degrees cooler than outside temperatures in the summer months. The atrium was a bold, untested idea and a logical alternative to air conditioning in the desert.

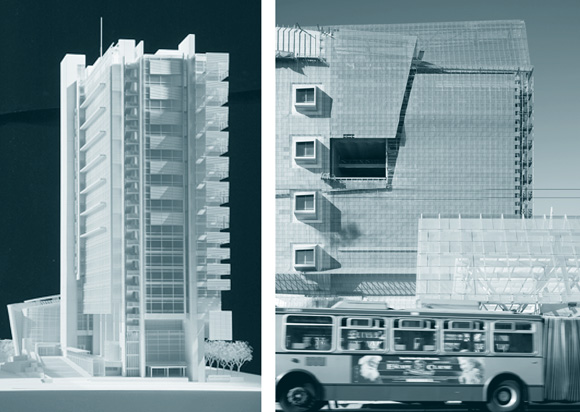

Leadership in sustainable environments is being reinforced with the passively air-conditioned San Francisco Federal Building. In addition to providing operable windows throughout the facility, the new Federal Building, originally authorized in 1988, incorporates skip-stop elevators and on-site childcare. Architecturally, the Morphosis design defies traditional styling of San Francisco high rises. No other developer in the city would take these risks on a 450,000 square foot project.

In addition to environmental stewardship, GSA understands the balance of community needs and national design objectives. The architectural implications of this balance are demonstrated with the federal courts program. The reconstruction of our justice infrastructure was a primary push for design excellence. But it also provided an exciting opportunity to test diverse themes in contemporary American architecture. The courthouse program applied nearly identical functional and aesthetic criteria to projects throughout the country. Therefore, these courthouses provided a template in which architectural expression was the major variable. Moore Ruble Yudell’s Fresno California Courthouse and Mehrdad Yazdani’s Las Vegas Nevada Courthouse are dramatic illustrations of this variety. Each project springs from identical functional criteria and vision statements, but each is individually appropriate for the local landscape and culture. Following the guiding principles from 1962, GSA recognized that creating this variety and texture begins with the architect selection process.

The Design Excellence program should be evaluated comprehensively based on its contribution to construction at all levels of government. Individual projects have achieved success based on a wide range of variables. But preserving the qualifications-based selection process was GSA’s most important step in creating a national portfolio of distinguished public buildings. Not surprisingly, this is where the democracy of the public bidding process generates the greatest benefit for architects. By encouraging the entire architectural community to compete for its business, GSA has remained fresh in its thinking and bold in its actions. Where else can relatively unproven talent be seen as a competitive equal to architecture practices with a multi-generation lineage? These neophytes are not always selected, but the lay and professional jury process is enriched by the exposure to forward-thinking ideas. Architects are judged on their talent and persuasive thinking. And with the help of private sector peers, many rooted in academia, GSA is fed a steady diet of the avant-garde. The richness of architectural talent interested in public work is the direct result of Design Excellence and GSA’s inspired architectural patronage.

Not to be forgotten is GSA’s successful incorporation of art with architecture. One-half percent of the construction budget is dedicated to creating site-specific artwork to support and enhance the architecture. These commissions are as important to the Design Excellence legacy as architecture. Graphic design and landscape design are also contributing factors to the program.

In a relatively short time, GSA’s architectural patronage has supported extraordinary innovation in design, the arts, and construction technologies. This inspired leadership is not the result of an entrepreneurial campaign but a fundamental shift in institutional culture. A recent leadership transition maintains the momentum started in 1994, so that, like the Medici, GSA can be the catalyst of genius for decades to come.

Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture

From Report to the President by the Ad Hoc Committee on Federal Office Space, June 1, 1962.

1. The policy shall be to provide requisite and adequate facilities in an architectural style and form which is distinguished and which will reflect the dignity, enterprise, vigor, and stability of the American National Government. Major emphasis should be placed on the choice of designs that embody the finest contemporary American architectural thought. Specific attention should be paid to the possibilities of incorporating into such designs qualities which reflect the regional architectural traditions of that part of the Nation in which buildings are located. Where appropriate, fine art should be incorporated in the designs, with emphasis on the work of living American artists. Designs shall adhere to sound construction practice and utilize materials, methods and equipment of proven dependability. Buildings shall be economical to build, operate and maintain, and should be accessible to the handicapped.

2. The development of an official style must be avoided. Design must flow from the architectural profession to the Government, and not vice versa. The Government should be willing to pay some additional cost to avoid excessive uniformity in design of Federal buildings. Competitions for the design of Federal buildings may be held where appropriate. The advice of distinguished architects ought to, as a rule, be sought prior to the award of important design contracts.

3. The choice and development of the building site should be considered the first step of the design process. This choice should be made in cooperation with local agencies. Special attention should be paid to the general ensemble of streets and public places of which Federal buildings will form a part. Where possible, buildings should be located so as to permit a generous development of landscape.

Mark Tortorich, FAIA, is the Vice President for Design and Construction at Stanford University Medical Center overseeing the hospitals’ renewal and replacement program. From 1983 to 1998, Mr. Tortorich was a manager at GSA’s Regional Design and Construction Division in San Francisco and a national Design Excellence Advisor. He was appointed a private sector Design Excellence Peer in 2000.

Originally published 1st quarter 2007 in arcCA 07.1, “Patronage.”