Why Merced?

Many Californians question why the Regents of the University of California and the California State Legislature decided, over a decade ago, to expand the UC system with the creation of a tenth campus. Others take the question one step further and ask why locate the tenth campus in the Central Valley. Not stopping there, still others ask: Why Merced, of all places?

Throughout California, UC Merced is the subject of both praise and derision (and perhaps apathy). Many see the transformative power of a UC campus as a catalyst for the kind of prosperity that could never come from the economic, social, and cultural systems already in place within the Central Valley. On the other hand, Merced is no closer to many Valley residents than Disneyland, and a UC degree can be earned from any of the existing nine campuses, which are all within driving distance. Why build another?

Up and down the Highway 99 corridor, the polemic is exercised in the editorial columns and letters to the editor of every local newspaper. Furthermore, the existence of UC Merced is controversial among the myriad political constituencies connected to this academic powerhouse institution that has led the way in everything from building the Bomb to unlocking the human genome.

Those in opposition or simply ambivalent should consider that regional economic and demographic projections indicate that unprecedented growth is taking place and will continue for decades in the geographic center of the state. Traditionally, the Central Valley has been a region plagued by high crime, high unemployment, low matriculation rates, and low-paying, bleak-future jobs. The region is home to immigrants from a wide range of cultures. Many students are the first in their family to attend college. For these reasons, many argue that Central Valley students have been and will continue to be underrepresented in the UC system, either because students are unprepared for the rigors of a UC education, or because they are simply unfamiliar with the benefits of attending a world-class university.

Why Not Fresno?

Forty-five miles south of Merced is Fresno, the fifth largest city in California with a population nearly ten times that of Merced. Fresno’s downtown began to falter in the 1960s when modernist town planning and traffic engineering principles called for the destruction of historic structures and streetscapes deemed unsafe and a physical deterrent to progress. Much of the once lively downtown was erased, leaving vacant lots and bad modernism as a legacy. The Central Valley as a region has suffered from the absence of a powerful urban center.

For argument’s sake, consider the positive outcome of knitting a UC campus within the remaining fabric of Fresno’s downtown. No strategy for sustainability would have been more “green” then recycling an entire downtown with the introduction of an urban university campus playing the role of economic, intellectual, and cultural engine. UC Merced is perhaps the greatest missed opportunity for the City of Fresno, but definitely one of the greatest benefits to the entire region.

When asked about the University’s decision to locate the tenth campus on 25,000 acres of wetlands away from a major city, campus architect Thomas Lollini, FAIA, points to the institution’s history, citing a pattern of “greenfield” development for UC campus sites. The campuses at Berkeley, Los Angeles, Riverside, and Irvine are examples of locations where the campus was there long before the host city grew to the campus edges. Photographs of the flatlands of Berkeley taken in the early half of the nineteenth century resemble the wide-open, gently rolling agricultural site selected for UC Merced.

Campus Architecture

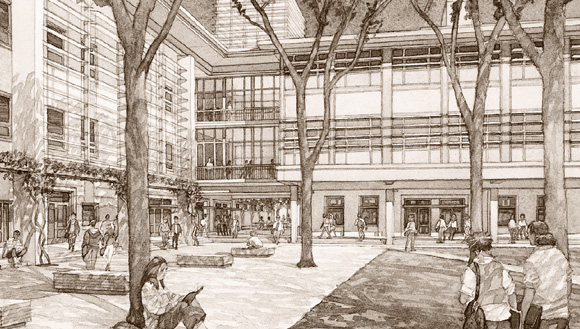

The other nine UC campuses are defined by some of California’s most memorable and important buildings, landscapes, and open spaces. UC Merced, as a place, is literally in its infancy, making it difficult to compare the campus to its mature counterparts. The campus master plan, developed by John Kriken of SOM with consultants Barbara Maloney and Richard Bender, has been tested by the construction of the first major buildings and open spaces. A composition of three recently completed major academic buildings forms the beginning of a quadrangle framed by indigenous tree plantings and pedestrian thoroughfares, with views of an existing waterway that runs along the campus edge. The initial moves are brilliant.

The buildings include the Leo and Dotti Kolligian Library (Skidmore Owings & Merrill, San Francisco, with Fernau & Hartman), the classroom and office building (Thomas Haecker and Associates), and a science and engineering building (EHDD Architecture with Leo A. Daly). Other non-academic buildings include student housing and dining commons (BAR and Taylor Group Architects), the Joseph Edward Gallo Recreation Wellness Center (Sasaki Associates), and the central plant (a recent AIACC Honor Award Recipient, Skidmore Owings & Merrill, San Francisco).

Agricultural buildings express a beauty derived from pure function and engineering clarity and are not intentionally stylized. That sense of rigor and purpose has been skillfully translated in the forms, massing, detailing, and materials exhibited in the inaugural campus buildings. The first architects on campus were charged with the task of identifying a vernacular architecture derived from the culture, landscape, and dominant building forms and typologies unique to the Central Valley. Lollini cites the predominant use of concrete, metal, and glass found in agricultural buildings that dot the landscape as the formal and tactile inspiration for a bold vernacular that is rooted in the agrarian environment of Merced.

The science and engineering building successfully translates the purposeful formal clarity of a cotton gin, almond huller, or grain elevator in which plan configuration, form, and material use are generated by function alone. The fritted glass louvers that create an exterior, three-story tall arcade create a noticeably cooler zone between the harsh summer sun and the conditioned interior spaces. Apertures at the ends of the arcades skillfully capture prevailing winds to channel pleasant breezes along the interior perimeter walls of the arcade, providing a cool place to linger on a hot afternoon. Massive concrete walls and columns support elegantly detailed light monitors, reminiscent of building compositions one sees along the two-lane, pot-holed agricultural roads between the highway and the campus. This building seems to belong here.

All present and future campus buildings will achieve LEED silver certification from the U.S. Green Building Council. Furthermore, UC Merced became the first campus submitted into the USGBC Portfolio Program, seeking ten baseline points for the campus infrastructure. These baseline points can be applied to all individual future buildings for LEED certification.

The Campus and the Community

Now that the campus is online and functioning, Lollini is focusing on the way in which architecture can be used to reinforce an urban design plan that will bring the town up to the campus. The urban design plan calls for the integration of approximately 12,000 residential units in both multi-family and single-family configurations, along with a community center and other uses and amenities that will begin to integrate town and gown.

The urban design plan, when realized, will respond to the inevitable growth that occurs with the advent of a major university with the transformative power to change an entire region. It will guide collaboration with the City of Merced to prepare for the transition from farming community to college town.

Author Paul N. Halajian, AIA, is a principal of Taylor Teter Architects, a Fresno-based firm. After working in the San Francisco office of EHDD Architects, he returned to the Central Valley and is working on a range of projects throughout the Valley, including a number of urban design projects that focus on the revitalization of Fresno’s downtown. He is chair of the arcCA editorial board.

Originally published 4th quarter 2006 in arcCA 06.4, “The UCs.”