As the interior design profession matures, it has become important to some in that community to be recognized as professionals with unique educational qualifications and knowledge. Those members have cried out for their profession to be distinguished from the practice of interior decorating, as well as from the practice of un-trained persons who can market themselves as interior designers without legal consequences.

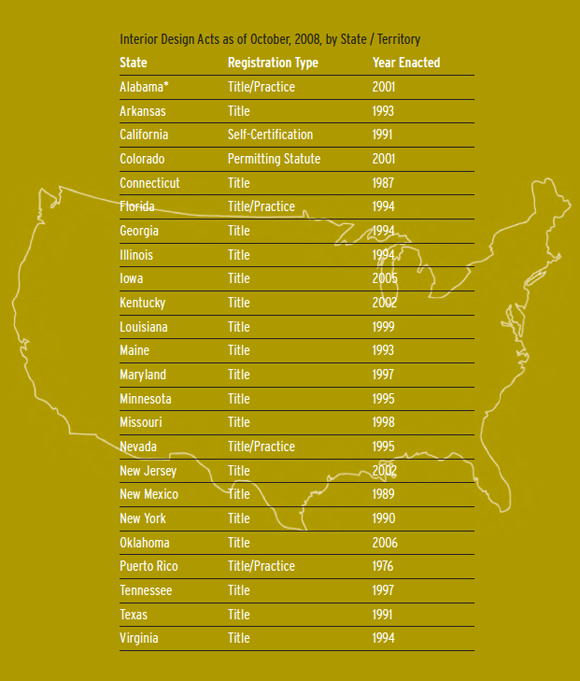

Proponents of regulation seek to promote either Title Acts, which limit who can use the title, or Practice Acts, which limit who can perform the service, on a state-by-state basis. (For example, the term structural engineer is controlled by a Title Act, whereas the term civil or electrical engineer is controlled by a Practice Act—which is why you may find “civil engineer” on your structural engineer’s stamp.) Opponents of regulation cite economic hardship and discrimination due to the requirement of accredited education and qualifying exams.

What seemed to be a fairly cut and dried issue has spawned a civil war among interior designers and practitioners, pitching membership organizations and even members within the same organization against one another. Besides this internal disagreement, the complexity has increased with the overlapping jurisdiction between architects and interior designers on interior projects.

State-by-state battles by interior designers have mostly taken the form of legislation to establish a Title Act, a Practice Act, or some hybrid form of the two. This year in California, Senators Leland Yee of San Francisco and Ron S. Calderon, representing parts of Los Angeles, introduced California Senate Bill 1312, which was eventually defeated. This legislation proposed to create official state licensure and regulation for “registered interior designers.” It would replace the California Architects Board with the California Architects and Registered Interior Designers Board.

Proponents of legislative regulation of the interior design profession include the American Society of Interior Designers (ASID), the International Interior Design Association (IIDA), the National Council for Interior Design Qualification (NCIDQ), and the Interior Design Coalition of California (IDCC). They cite public health, safety, and welfare as well as increased professional status and independence for interior designers as the main reasons for regulation initiatives.

According to Randy Stauffer, co-Vice President of Government and Regulatory Affairs for its Southern California chapter, IIDA is in support of Practice Acts that will allow registered interior designers to have the authority to stamp and seal drawings. As Stauffer notes, currently, depending on local jurisdiction, certified interior designers have to obtain the stamp and signature of another professional (such as an architect or structural engineer) when they submit for plan check.

In a telephone interview with Bruce Goff, Legislative Director for the IDCC and national board member of ASID, he clarified that the drive to register interior designers originated with the need to clarify vocation versus profession and to ensure that interior designers can practice to the full extent of their knowledge and experience. The proposed Practice Act will not preclude anyone from calling oneself an interior designer, but will create a tiered categorization of interior designers. The legislation will define the activity areas of registered interior design practice relative to public health, safety, and welfare and code impact.

In an example to clarify the Act’s intent, Goff spoke of a set of drawings submitted for plan check that may include pages stamped by the interior designer (for design intent), structural engineer (for structural design and calculations of load bearing members), and architect (for the master exiting system and other code impacted areas). Goff also drew an analogy to the subcategories of the nursing profession, in which their activities are also governed by tiered registration. As he further remarked, the three E’s (education, experience, and examination) should form a threshold to qualify an individual for the scope of work commensurate with the quality of the vetting measure.

According to AIACC Director of Legislative Affairs Mark Christian, the AIA California Council has, in the past, supported a simple Title Act, but not a Practice Act such as SB 1312. The Council believes that the state should not interfere in the marketplace by restricting the production of services, unless such interference is needed to protect the health, safety, and welfare of the public. It believes that no evidence has been put forth for that argument.

Also, interior designers in California can already operate within the exemptions of Section 5538 of the Architects Practice Act and can submit plans to building officials within those guidelines. Those guidelines do not prohibit anyone from furnishing drawings, specifications and data: (a) for nonstructural or nonseismic storefronts, interior alterations or additions, fixtures, cabinetwork, furniture, or other appliances or equipment; (b) for any nonstructural or nonseismic work necessary to provide for their installation; or (c) for any nonstructural or nonseismic alterations or additions to any building necessary to or attendant upon the installation of those storefronts, interior alterations or additions, fixtures, cabinetwork, furniture, appliances, or equipment, provided those alterations do not change or affect the structural system or safety of the building.

A major opponent of the licensure of registered interior designers is the National Kitchen & Bath Association (NKBA), consisting of a membership primarily serving residential markets. In testimony before the Pennsylvania House Committee on Professional Licensure in September 2007, NKBA’s General Counsel and Director of Legislative Affairs, Ed Nagorsky, stated that “a handful of interior designers . . . seek to monopolize the industry” and that there is no evidence that the public is being harmed without the legislation.

AIACC’s Christian notes that SB1312 would have prohibited the interior designers represented by the NKBA and their allied opponents from offering interior design services, and that, depending on their education and experience, it may be difficult for residential interior designers to become licensed.

Therefore, it would have created a caste-like system for interior designers in California, with residential interior designers at the bottom. In Maclachlan’s article in Capitol Weekly, Christian characterized the bill as a “power grab cloaked behind the rhetoric of ‘protecting the consumer.’”

Also in opposition is the Interior Design Protection Council (IDPC), whose main purpose appears to be to organize and educate interior designers on how to effectively resist ASID-supported legislation and protect their livelihoods. Another allied opposing voice is the California Legislative Coalition for Interior Design (CLCID), which is concerned about the exam and prerequisites putting designers out of business.

Also vocal and active against licensure is the Institute of Justice (IJ), self-described as a libertarian public interest law firm, but also referred to in Capitol Weekly as a conservative legal foundation funded by the Coors and Walton families. In a case study released in November 2007, the Institute professed to have documented “a long-running campaign led by the American Society of Interior Designers (ASID) to expand regulation of interior designers in order to put would-be competitors out of business under the guise of ‘increasing the stature of the industry.’”

The national AIA maintains that the protection of the health, safety, and welfare of the public is paramount, and that architects and engineers are the only professionals who meet the threshold of licensure and registration. The AIACC also wrote a letter to Senator Mark Ridley-Thomas opposing SB1312. It stated that, “Interior designers often are an integral part in the design process, and frequently work with architects in planning and designing interior spaces . . . . However, their knowledge, acquired through education and experience, does not include the whole building system, and this knowledge is necessary to protect the health, safety, and welfare of the public.”

California has maintained a self-certification process since 1991 (California Business and Professions Code—Sections 5800-5812). This is how related interior design organizations became part of the discourse. The California Council for Interior Design Certification (CCIDC), a non-governmental organization, administers the IDEX-California examination (which, beginning this October, replaced the previously required combination of one of three competing national exams and the CCRE (California Codes and Regulations Exam)).

Candidates must also provide proof of combined work experience and interior design education, totaling six years with an accredited degree or eight years without. The Council for Interior Design Accreditation (CIDA) is an independent, non-profit accrediting organization for interior design education programs at colleges and universities in the United States and Canada. A full listing of accredited interior design programs is available on their website, www.accredit-id.org. The majority of the California community colleges are not on this list, hence the burden of many interior designers with a degree from an unaccredited school to produce evidence of two more years of experience than those who received an education from an accredited school (likely a more expensive education).

This civil war among interior designers gets even more complicated when we factor in that many architects who practice primarily interior architecture or interior design are active members of both the AIA and IIDA or ASID. Some architects in larger firms practice alongside interior designers daily and collaboratively and find it difficult to decide where to stand on this debate. As part of the AIA’s Knowledge Community, the Interior Architecture Advisory Group has begun outreach efforts to the interior design community through the IIDA. Instead of attempting to resolve any conflicts, it is approaching the contact on a member-to-member basis to begin the dialogue about this complex issue that will persist for many years to come.

Author Annie Chu, AIA, is a principal of Chu+Gooding Architects in Los Angeles, focusing on projects for arts-related and education clients. Notable projects include the Masters of American Comics exhibit at MoCA and Hammer Museum and Architecture of R.M. Schindler exhibit at MoCA, renovation and addition to the 1950 Harwell Hamilton Harris masterpiece English House and the Kentucky Museum of Art and Craft. She is a member of the arcCA editorial board and the AIA Interior Architecture Advisory Group.

Originally published 4th quarter 2008, in arcCA 08.4, “Interiors + Architecture.”