If the 1990s began in 1988 with MoMA’s “Deconstructivist Architecture” exhibition, they died with the closing of the critical journal of architecture Assemblage, whose forty-one issues spanned from 1986 to 2000. —Paulette Singley

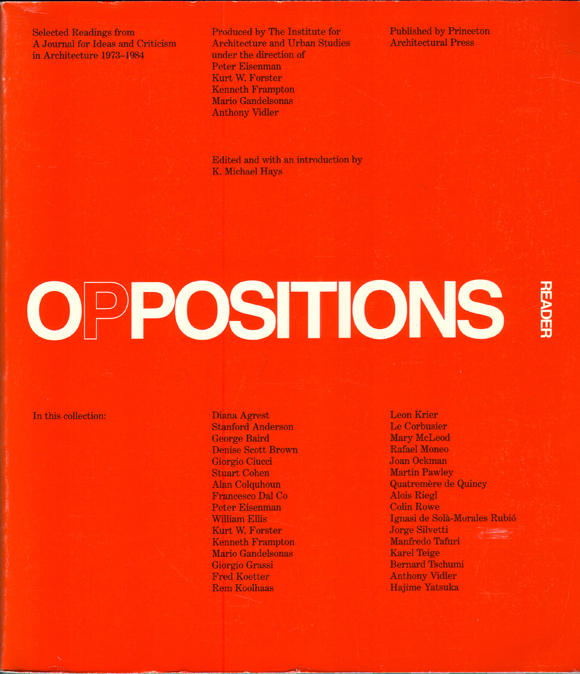

Patricia Morton: Theory’s ascendancy within architecture culture can be traced in the rise of new, outcast institutions, such as the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS, 1967-1985) in New York and the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc, founded 1972) in Los Angeles. Oppositions, published by the IAUS, was the original for Assemblage and its successors; it was a livelier, more topical version of what has become a somewhat tired mix of history, theory, and criticism.

The members of the IAUS elite corps are now the gray-haired establishment of architecture (Peter Eisenman, Anthony Vidler, Mario Gandelsonas, Diana Agrest, Steven Peterson, Rem Koolhaas, et al.), but they were rebels who broke with International Modernism and brought politics, theory, and history to the fore. A similar thing has happened to the SCI-Arc establishment, but LA’s geographical distance from the dominant East-Coast schools has kept SCI-Arc closer to the edge of both practice and theory.

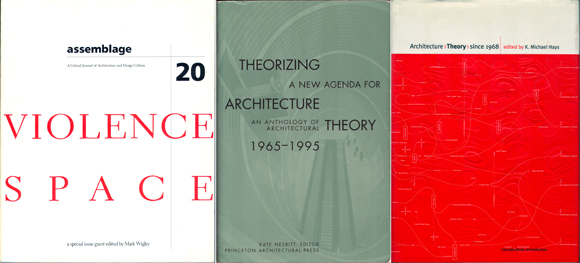

Paulette Singley: The publication of two anthologies—Kate Nesbitt’s Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture: An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965-1995 (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996) and K. Michael Hays’s Architecture Theory Since 1968 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998)—signaled both the rise and the demise of architectural theory. These publications translated what had been an exclusive, rarified bibliography and vocabulary into a semi-transparent and more accessible format and in so doing popularized an elitist body of knowledge.

They collected in one place most of the most important essays that influenced this moment in time, bringing together writings by architects, architectural theorists, architectural historians, and philosophers. As the title of Vidler’s The Writing of the Walls: Architectural Theory in the Late Enlightenment (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 1987) suggests, this moment was concerned with writing, language, reading difficult texts, and seeking architecture’s theoretical potential.

Morton: In the 1990s, the critique of Modernism was codified and institutionalized, the young rebels became middle-aged culture stars, and Ivy-League architecture schools dominated High Architecture discourse and practice. Hays’s and Nesbitt’s anthologies froze the discourse and its history into a canon, which could then be ignored as outdated, part of the previous generation of discourse. What they left out was as interesting as what they included: sociological investigations of built form, political activism, polemics outside (or against) the academy, guerilla building, community design.

Singley: With theory serving as the operative term in design education, a new position emerged in architecture schools, that of the architectural theorist. Theory was neither a homogenous nor a consistent discipline, but in its more aggressive moments it proposed a totalizing regime while simultaneously calling for the end of totalizing regimes. In disclaiming grand narrative, it in fact constructed one.

In many circles, it was not simply theory that held sway, but a particular brand of theory called postmodernism. But here is where it gets tricky. This was not the postmodern classicism of Robert Venturi and Michael Graves, which sought architecture’s potential to communicate through the language of form, but rather a deep reliance on philosophy, on the legacy of Marxist thought, on Jacques Derrida’s practice of deconstruction, post-structuralist analysis, and the death of the author—the notion that texts beget more texts, that nobody authors anything. Postmodernism, in this guise, entertained the work of both Eisenman and Venturi.

Morton: Could it all be a hangover from the Beaux-Arts revival? The figural, the decorative, and internally generated form have been the dominant impulses in architectural thinking, although no longer clothed in historical language.

Singley: If for some, postmodernism never really existed, and for others it was politically irresponsible, then for yet others it was a site of liberation, intellectual freedom, and class empowerment. In its quasi-dialectical mode, the periphery was the center, surfaces were deep, and ornament was structure. All of the groups formerly excluded from power were given voices and tools with which to operate.

Moreover, writing about architecture opened up to include alternative modes—personal voice, fragments, letters—the simultaneous voicing of many positions. Out of this wildly diverse range of influences, subjects and styles of writing that had been excluded found space in publication—feminism, queer theory, postcolonial theory, etc.

Morton: The old slogan “the personal is political, the political is personal” could be the motto of the 1990s, but it sometimes devolved from a concern with the political aspects of private life into an excuse for the cult of the personality. Politics was drained of actuality; no social mission was left for architecture in the flurry of discourse and disciplines that absorbed the culture. Koolhaas is the poster child for this retreat from a critical architecture (or, some would say, abdication of responsibility).

There were exceptions, like Sam Mockbee, who did exquisite, revolutionary buildings in the service of poor people. His work was a revelation: you didn’t have to design the equivalent of Birkenstocks to bring a social conscience to architecture.

At the same time, feminism provided a private/public politics and a way of creating a political practice that wasn’t about bleeding- heart liberalism or urban planning, which seemed to be the only alternatives. And (speaking of anthologies), three important collections of feminist work appeared in 1996: The Sex of Architecture, Diana Agrest, Patricia Conway, and Leslie Kanes Weisman, eds.; Architecture and Feminism, Debra Coleman, Elizabeth Danze, and Carol Henderson, eds.; and The Architect: Reconstructing Her Practice, Francesca Hughes, ed. There was an explosion of interest in gender, sexuality, and identity and their expression in architecture.

Also in the 1990s, environmental activism and sustainability emerged as a persistent political arena that’s now of actual importance, with global warming on everyone’s mind. This is an area where architects have the power and knowledge to have a huge impact on the public realm, even given their limited role in the design of the built environment.

Singley: Where language, discourse, and representation represent one end of the intellectual spectrum, the other end might be the body, phenomenology, and practices of everyday life. Michel Foucault emerged as a dominant influence for critiquing the power of corporeal disciplines and their corresponding architectural institutions. In bodily and cognitive vision, architecture and theory found common ground—in frames, points of view, systems of surveillance, or absolutist planning techniques. Vision and visuality emerged as dominant obsessions of designers (at least to the extent that reflective surfaces could be fetishized).

Morton: Technology had an enormous impact on the obsession with sight and visuality, and not just from the theory side. You can “see” things differently with computers. CAD and other design software transformed architecture, and there’s a real generational divide between those architects who learned to design on the computer and those who had to learn later (or hire people who know how). And there was a certain amount of sorting out, equivalent to downsizing in the manufacturing industries, because firms could produce drawings with many fewer staff.

In the early 1990s, during the economic doldrums before the Clinton-era boom years, architecture students went into animation studios, which had lucrative work, while architecture firms were closing and cutting back. Simultaneously, architects learned how to use algorithms, tweak the programs, or simply use the clunky form-generating software to generate new aesthetics, new cool stuff.

Forms that had been painstakingly plotted by hand or in model (early Gehry) or generated by “chance” operations (Eisenman at the Wexler) could be turned out in little time with the right software. Surface, pattern, spatial ambiguity, warped roofs, splintered walls, all the attributes of what was variously called Deconstructivism or blob architecture or other terms.

What’s most surprising is the degree to which this “new” work looked a lot like handmade work (think of Zaha Hadid’s Hong Kong competition entry), and pretty much everything looked the same. Maybe technology isn’t determinant.

Singley: Marshaling such heady intellectual prowess also led to a kind of intellectual terrorism in which words were deployed as weapons and political incorrectness pounced upon. Is it any wonder that there was a backlash, and that this moment of intensity was not sustainable? At times the voices became shrill, the architecture increasingly irrelevant, and the ability to generate form nearly abandoned. Theory risked theorizing itself and architecture out of existence. The jouissance and sheer ecstasy of this time period produced an excess of words that eclipsed the necessity of design and eventually eclipsed itself. Today, the volumes of Derrida, Jacques Lacan, and even Walter Benjamin sit on bookshelves collecting dust.

Morton: Given the corporatism of Robert A.M. Stern, Michael Graves, and Rem Koolhaas, why not some jouissance, some joy, some decadence, even if it was “just” words? What happened to the delirious? Architects looked for alternatives. Sometimes they were frivolous, but sometimes they were productive and exciting. There were collaborations between artists and architects, strange amalgamated and hybrid practices (the HEDGE Collective in Los Angeles or the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York, for example), and practices that seemed to have nothing to do with “architecture.” These new practices have led to an opening out of architecture, and a new concern for melding theory with practice.

Patricia A. Morton is Chair and Associate Professor of architectural history at UC Riverside. Her book on the 1931 Colonial Exposition in Paris, Hybrid Modernities, was published in 2000 by MIT Press. Her current research focuses on “bad taste” in 1960s architecture and its relation to postmodern architecture. She has published widely on architectural history and issues of race, gender and marginality. Paulette Singley is Program Head of Architectural History and Theory in the School of Architecture at Woodbury University in Los Angeles. She co-edited Eating Architecture and Architecture: In Fashion and has been published in Log, ANY, Assemblage and several critical architectural anthologies.

Originally published 1st quarter 2008, in arcCA 08.1, “‘90s Generation.”