Jono Coles works between traditional architectural practice, art practice, teaching, writing, and alternative development to critique systems of value. arcCA DIGEST spoke with Coles about his M.Arch. thesis, Approaching Value, completed under Dr. Neyran Turan at UC Berkeley, Spring 2024. Its development parameters were explored in Christopher Calott’s Small-Scale Infill Development Seminar, in UCB’s Abbey Master of Real Estate Development + Design program.

Can you begin by giving us an overview of the project?

The project is a proposal for a new typology of co-housing that locates architectural agency within zoning, building codes, and contemporary financial systems. Its novelty as a housing model is derived from its unique tripartite definition:

1) it is financed and permitted as two adjoined single-family homes,

2) it is legalized and sold as a set of six condominiums, and

3) it can be further divided and sublet as up to twelve studio apartments.

This strategy is inspired by the peripheral neighborhoods of American second-cities like Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and Oakland, where fluctuating socioeconomic factors cause neighborhoods to vary dramatically in density over time. In these areas, it is common for classic typologies like rowhouses to flicker between conditions of single-family occupancy, vacancy, and multifamily occupancy depending on demand. The project accounts for these common, temporal cycles of reuse, putting forth a design-for-adaptation model that sneakily inserts density into single-family neighborhoods.

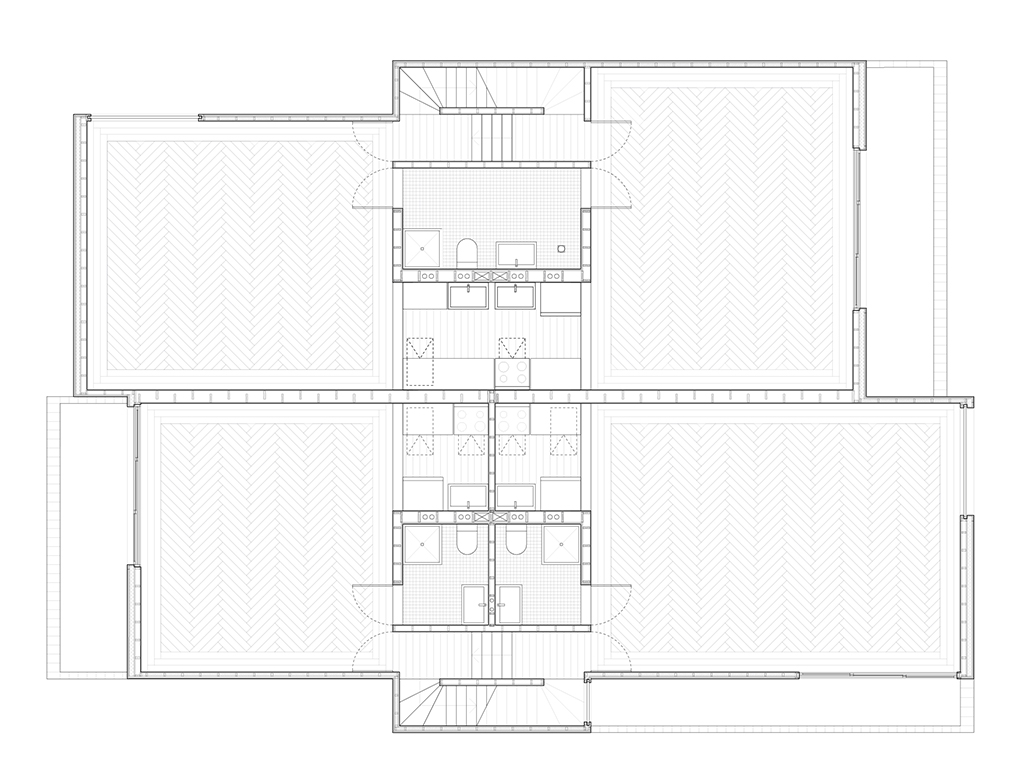

I’ll explain how this works architecturally: the building appears in plan as a standard three-story duplex, with a circulation and utility core dividing each floor of the houses into two large rooms. The arrangement of this core allows doors to enclose the central stair, giving private entry to each of the large rooms, while the plumbing walls allow for one or two bathrooms and kitchens on either side. Depending on the configuration of the core elements, each half, floor, or room of the building can act as a separate dwelling unit.

The expertise required to administer this flexibility, as well as its hazy legality, means that the project is envisioned through a bastardized architect-as-developer model. This type of project is unlikely to be initiated by a client; a cooperative model of architectural practice is imagined to co-finance the project, operate and maintain it, and administer its

various reconfigurations over time. The project does not differentiate between contemporary issues of design and practice; increasingly for young architects, new models of living cannot be achieved through design alone, but must be paired with alternative models of practice and ownership.

What situation is the project responding to?

The project is deliberately situated within two intertwined contexts, the first being the contemporary systems of value that affect models of architectural practice, and the second being the effects of these systems on design.

By systems of value, I’m referring to the political and economic apparati intended to regulate the financialization of the built environment: broad examples would be systems like zoning, debt securities, liability law, and so on. A more specific example would be the requirement for two means of egress in R-3 occupancies, an archaic building code item which has birthed uniquely American housing typologies like the five-over-one. These systems combine to limit design possibilities, and oftentimes exclude architects from the design process entirely.

These same value systems exert significant pressure on contemporary architectural practice; the widening division between the Architect of Record and Design Architect can be traced back to the emergence of the “Core and Shell” deal structure in the 1970s, for example. This inability to approach systems of value is burdening the profession on broader scales: many practices suffer unsustainably low and continually shrinking profit margins, rampant and normalized exploitation within offices themselves, and paralysis in the face of environmental catastrophe. In summary, young practitioners are faced with a choice: enter highly pressurized conventional practice with limited agency, or develop alternative models of practice. This project is an optimistic dry run at the latter.

How are you responding to this situation?

The response is to champion critique as a generative and optimistic force. Whatever new form of practice I propose is inherently born from a critical position towards these systems of value, but that does not mean that it must be negative or pessimistic. This is where the idea of the loophole – the concept of which is adapted from artist Harrison K Smith – becomes relevant: systems of value are not perfectly crafted, in revealing and peaking through their inconsistencies, we can produce new imaginaries with entirely different design sensibilities and models of practice.

Loopholes are common in architectural practice but are rarely discussed. We all have certain tricks and hacks, whether it be scaling up material hatches to make a building appear smaller in permitting, or leaving certain details out of the build set to save money (both of which this project does). While most loopholes have minimal effect and are mostly just convenient, this project tries to take them as far as possible, exaggerating materials beyond colloquial definition, and ultimately forming a tripartite identity to the project entirely.

Could you discuss some of these loopholes further?

I mentioned the exaggeration of materials – the most obvious place this is happening is with the project’s brick veneer cladding. Some historic zoning codes mandate brick facades despite the rising rarity and expense of real brick, which has subsequently caused an increase in usage and availability of faux brick (AKA brick veneer). Veneers are detailed as rainscreens, meaning they are barely functional and almost purely aesthetic. The loophole here is to leave the joint of the brick un-tooled; this is called a “weeping joint” and is common in industrial bricklaying. In the cost estimates we received for this project, the labor avoided by not tooling the joint saved between $15,000 and $40,000, depending on the format of the contractor’s estimate. That represents almost a 20% reduction in envelope cost for the project.

While this material loophole is efficient from the standpoint of labor and economy, these sincerely deceptive considerations of tectonics can develop new aesthetic sensibilities, as well. In this case, the façade becomes furry and rough but hard at the same time, exaggerating the contrasting smoothness and depth of the punchy window detail. It also gives a playful character to an otherwise stoic building.

Other materials are played with in similar ways. An inflated mockup of herringbone parquet floors is built using plywood offcuts, for example. This strategy similarly decreases installation time, as there are fewer pieces and the allowable installation tolerances grow. At the same time, it miscommunicates the scale of each room in the permit set, all while maintaining the ability to be appraised as a luxury finish.

As I was playing with the value of materials in various ways , I became interested in getting the project estimated and appraised in several different ways, as well. In fact, some loopholes arose from this process. For example, appraising the project as two single-family homes yielded the highest sale value of $1.5M. Interestingly, this is because the brick exterior boosted the value of its comparable sales. The mode of architectural representation used to communicate each material assembly also influenced the estimate. The contractors who were sent window details charged a premium for the specific assembly, whereas those who were sent renders of the window gave lower estimates, as they assumed the least expensive assembly that would generate the visual effect. In these cases, less design is cheaper.

What important considerations might you be neglecting?

The project at its current state is admittedly speculative. While it does sincerely approach systems like zoning, finance, and building codes, there are subjectivities and opacities intrinsic to these systems that only fully reveal themselves through actually executing the project. In the countless conversations I’ve had about the project with planners, developers, builders, and architects, it is clear that skirting around the rules so dramatically can cause a range of legal oversights. More broadly, some have said the project is really an exploration of risk and liability, while others have offered to put me in contact with their lawyers. More specifically, some have said that the project’s viability comes down to how the plumbing wall is detailed, how the additional kitchens are built out, or whether the winder treads pass non-conformity inspections. In deliberately exploring gray areas, a million things could go right or wrong; what is most important to me is the learning process that comes with asking questions and occupying this new territory.

From arcCA DIGEST Season 17, “Adaptive Reuse.”