In the introduction, the editors state,

“We reject the optimistic prediction of future technology as a purely expressive medium. Such an assessment fails to acknowledge irreconcilable political, social and economic complexities. The tendency to negate technological developments is equally extreme and unrealistic.”

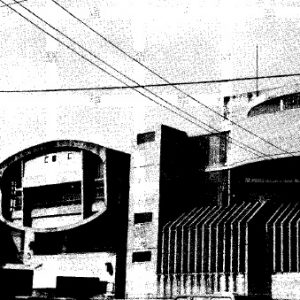

Presciently, in his article on the work of Arata Isozaki, British architectural critic Chris Fawcett asks, “If architecture can be simulated, is there any point in having it built?”

Here is the introduction, containing links to the individual articles. Following it are a table of contents (also linked) and a link to a PDF of the full issue. arcCA DIGEST is grateful to the Tulane School of Architecture and Dean Iñaki Alday for permission to republish this work.

With the ‘60s came a period of intense questioning in the U.S. The intensity has since faded, at least from the popular press, but the questioning remains. The experience of the ‘60s was indicative of a continuing and pervasive disillusionment with the premises underlying modernism in all of its forms in the first half of the century. Books such as Brent C. Brolin’s The Failure of Modern Architecture, Peter Blake’s Form Follows Fiasco and Daniel Bell’s The Coming of Post-Industrial Society mark the questioning of our heretofore unswerving faith in social planning, technology and elite decision-making.

Seeking to explore this questioning and the responses to it, which of late have come under the rubric “Post-Modernism,” in a multi-disciplinary way, we sought a central, representative issue which transcended professional boundaries. The issue which we chose and developed was that of technology and its relationship to the man-built environment. Much of the criticism of social, political, and architectural activity of the past fifty years has been concerned with this relationship. We asked students and faculty of Tulane University and members of the professional community to consider the question of the proper relationship between technology and the built environment.

We sought to restrict the freedom of response as little as possible, trying to develop a forum. Consequently, the responses we received cover a broad range of disciplines and points of view. Many express fully developed attitudes about the use of technology in the contemporary world; others only imply such attitudes. Many of the authors, as well, hold ideas in common; some, as we had hoped, disagree.

Browning’s article begins, as well, to touch upon the relationship between technology and the political process of building. Three articles, those of Michael P. Smith, Sandy Walkington and Timir Datta, continue to explore this relationship. Smith discusses the use of technology and its mystique to obscure citizen participation in the urban renewal process. Walkington describes the present world energy situation and then discusses the ramifications of the energy crisis on urban planning and policy making.

[Francis Schmertz’s “Men Working In Trees” captures in verse the distance between the Garden and the world we have made for ourselves.]

Most of the authors represented here are reacting against the too-sure acceptance and glorification of technology that accompanied Modern thought on architecture, social and urban planning, and world politics. Although Datta explicitly and Fritchie implicitly see technology primarily as a highly valuable tool, they both subordinate it to the greater human endeavor of artistic expression. It is indicative of a multi-disciplinary consensus that all portray a more modest stance toward the use of technology than the authors of the 1950s would have.

As editors, we are in sympathy with such a stance. We reject the optimistic prediction of future technology as a purely expressive medium. Such an assessment fails to acknowledge irreconcilable political, social and economic complexities. The tendency to negate technological developments is equally extreme and unrealistic.

Technology can be conceived of as a means to facilitate cooperation on all levels: between man and the natural world and between man and man. As an example, Charles Moore has recently employed public television “designathons” to achieve a populist based design for the Dayton, Ohio, riverfront. In this situation, through technics—specifically television and telephone—the design team was practically expanded to include all willing participants in a vital political process.

ARCHITECTURE AND THE TECHNOLOGICAL CULTURE, by Michael Zimmerman

MODESTY AND THE POST MODERN MOVEMENT, by Hugh Browning

THE LANGUAGE OF URBAN PLANNING AND THE ADVANCED CAPITALIST CITY, by Michael P. Smith

URBAN DESIGN BEYOND THE SOLAR PANEL, by Sandy Walkington

A DISCOURSE ON THE ARTS, BOTH APPLIED AND FINE, by Timir Datta

SOME EXPERIENCES WITH COMPUTER GRAPHICS, by Charles J. Fritchie

ARATA ISOZAKI, by Chris Fawcett

MEN WORKING IN TREES, by Francis L. Schmertz

TULANE ARCHITECTURAL VIEW, 1978, full issue

From arcCA DIGEST Season 4, “Data.”