After decades of zoning abuse and neglect, downtown Fresno’s Lowell Neighborhood is rising up through the efforts of grassroots organizations. Those leading the change yearn for the return of a community with strength in diversity and opportunity for socioeconomic mobility, restoring the same opportunities and character the neighborhood was built upon. Could the rebirth of a community be rooted in how we once designed neighborhoods? What can we learn from how we built in the past, and can we apply these design tools to future neighborhoods?

Beep. Beeeeep. The school bell sounds, and Samuel begins walking to his usual hangout spot. Block after block, the same pattern reoccurs. Home, duplex, apartment building, vacant lot – repeat. The properties he sees out of the corner of his eye form a snapshot of Fresno’s early history.

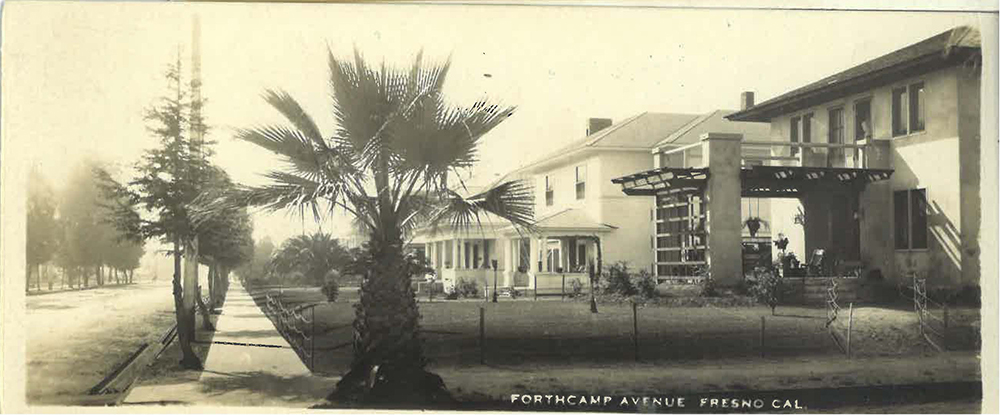

Every housing typology exists here in Fresno’s first streetcar suburb. The neighborhood is a showcase of American residential architecture, dating from pre-20th century to post-war cookie cutter: Craftsman, Neoclassical, Victorian, even catalog homes from Sears and Roebuck – decades of experimentation with construction methodology and style. Those residences still standing assert durability, and those on the market evoke a time of ornamentation and craft.

Samuel strolls past a group of up-to-no-goods throwing back 40s on a wide front porch, the neighborhood’s last true Queen Anne home – now a crack house, since being passed down through a grandmother’s will. In unworthy hands and disrepair, it is just another entry on the wish list of investors stalking the Lowell. Next to it sits a foursquare with more doors than windows, a sign of the many shifts in market forces since the neighborhood’s inception.

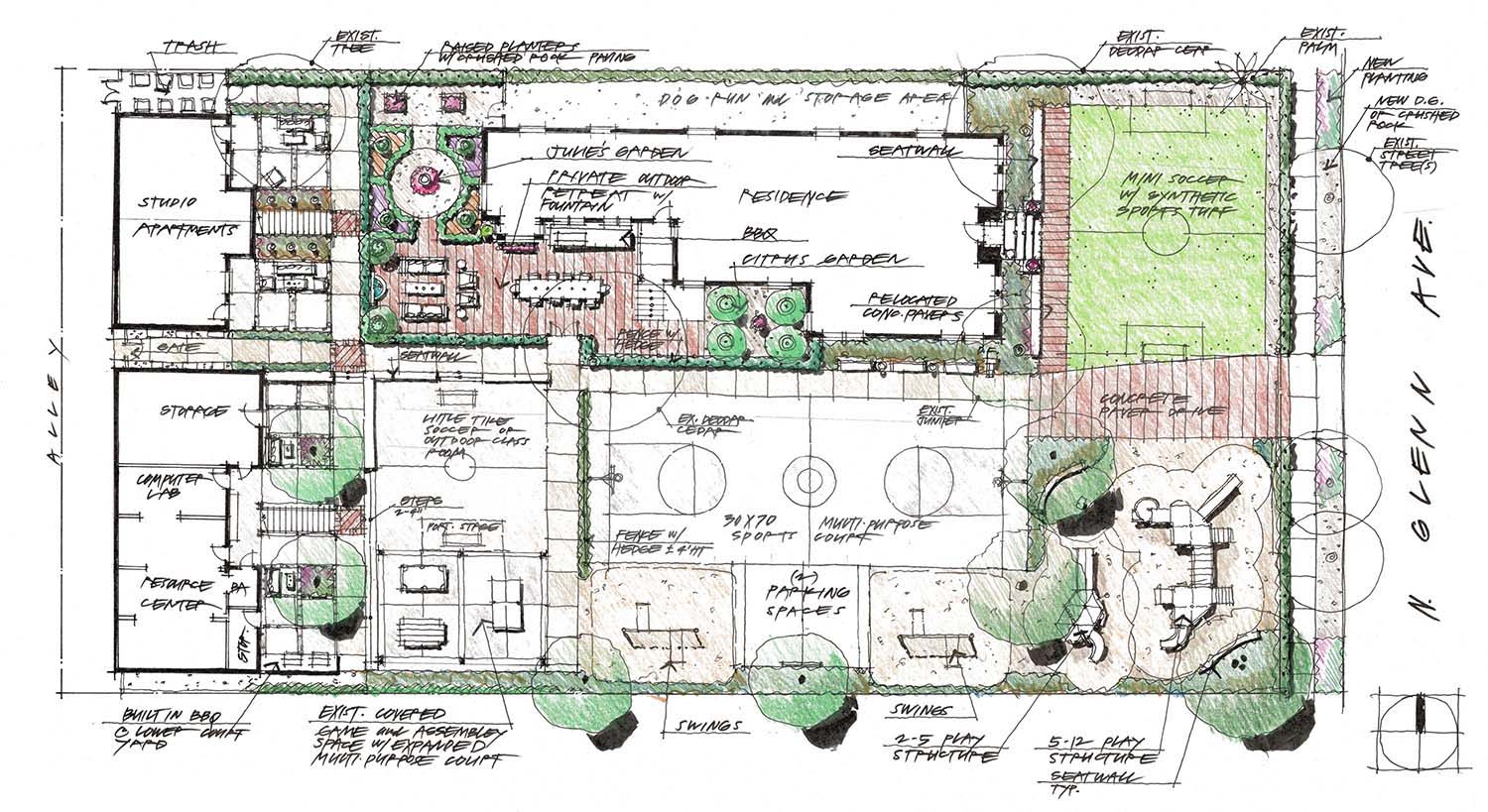

At last Samuel arrives at Martin Park. Don’t try looking it up in Google Maps. You won’t find it. The neighborhood haven is made up of Oscar Rodriguez’s front, back and side yards. A half-acre enclave, it encompasses swathes of artificial turf, a playground, and a community resource center of sorts. Once a carport stacked with apartment units above, it is now a refuge for bookshelves and tables covered with arts and crafts. It even has a computer lab – an exemplary form of urban hacking.

Martin Park is just one of many grassroots efforts restoring community in the Lowell Neighborhood. Beside a freeway overpass, a community garden with just enough daylight to grow anything goes a long way toward bringing residents together. In addition to buying and restoring historic homes, the Lowell Community Development Corporation partners with the local housing authority to redesign and rebuild blighted apartment complexes. At the Fénix (designed by R.L. Davidson Architects), tenants once dehumanized by slum-like conditions and a vacant parking lot now take their ease in a common courtyard, keeping an eye on things, promoting safety.

I first visited the Lowell Neighborhood last spring and soon grew fond of it – its history, architecture, and diversity and its story of socioeconomic mobility. It takes its name from abolitionist poet James Russell Lowell, for whom nearby Lowell Elementary is also named. In the summer, I volunteered for the Historic Home Tour, meeting residents, from young children, to engaged adolescents, to seniors who had been neighborhood leaders in earlier days.

What had been built in the Lowell was a direct reflection of two factors: the economy and the streetcar.

The neighborhood began in the 1880s when Fresno, experiencing rapid growth, needed to expand beyond its original town grid, which ran parallel to the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks connecting Northern California to Los Angeles. Through the early 1900s, tracts of farmland lying north of downtown were subdivided into arrays of rectangular blocks aligned north-south, a 45-degree shift from the old grid.

The working classes were the first to reside there. Square vernacular cottages on narrow, deep lots, simple in form and decoration, appealed to laborers with industrial jobs just west towards the tracks. Although minimal, the houses varied in expression. Neo-Classical and Victorian elements, such as columns, turned spindles, carved rafter tails, and even dentils, decorated the front porches. Toward the end of the 19th century, ornamentation popular during the Victorian era was becoming affordable through machine production.

As the 20th century approached, developments catering to middle class families desiring proximity to downtown offered more stylish homes, still modest in size but often two stories. Folk-Victorian, Upright, and Wing were popularized early on, later followed by Craftsman and American Foursquare. Some were built from catalogue designs. All were situated on larger plots of land with tree-lined streets and sidewalks.

In 1902, a streetcar line was extended north through the patchwork of ongoing subdivisions. Immediately, the area became desirable to business owners and professionals who could easily commute downtown. The remaining plots along the route became known as North Park, a posh development tailored for the affluent upper class. The subdivision was marketed as the “Nob Hill” of Fresno. Elite flocked from their downtown mansions, trading them for more progressive lifestyles. Open floor plans promoted indoor-outdoor living. The size of porches and windows grew. The homes embraced natural materials and craftsmanship, expressing the character of Colonial Revival. Long gone were the days of cluttered, compartmentalized Victorian homes.

North Park’s original residents were civic-minded people and city leaders, among whom was architect Benjamin McDougal, who assisted in platting the subdivision. North Park set a precedent for good neighborhood design. Features included contiguous setbacks, wide sidewalks, and lampposts all along the streetcar lines. Most importantly, the upper class were only one street over from the working class.

What unified the Lowell Neighborhood was the common need to be close to downtown and public transportation; that was more important than your neighbor’s economic status. Unlike the socioeconomic segregation occurring elsewhere in the city and throughout the country, the Lowell Neighborhood was organic and diverse from the beginning. That diversity is still evident today, despite the declines of the latter half of the 20th century.

By the 1920s, most of the Lowell Neighborhood was built out and encompassed eleven subdivisions, developed sporadically over time. The Great Depression shifted the market to affordable housing with the introduction of multi-family infill projects. In the 1940s, Spanish Colonial Revival bungalow courts became the innovative housing typology of the time. Worker cottages were still built towards the east and west of North Park, but in the more economical shotgun layout. Middle class homes were designed in the Minimal Traditional and the ranch style. About half of the larger homes originally built for the upper class were eventually partitioned into multi-tenant residences. Poor kids grew up alongside rich kids. Manners and mannerisms were passed along. Although harsh times were a challenge, opportunity was abundant.

By mid-century, with the rise to dominance of the automobile, the streetcar had been removed. Suburban flight soon initiated the Lowell Neighborhood’s demise.

In 1964, in an effort to reverse the exodus from downtown Fresno, the city converted six blocks of Fulton Street into a pedestrian mall designed by architect Victor Gruen and landscape architect Garrett Eckbo. The revitalization plan called for traffic to circulate around the new pedestrian zone and proposed a loop of freeways to surround the overall urban core. The east-west portion of the loop, Highway 180, would sever the historic North Park in half, forever disconnecting the Lowell from the interwoven fabric of neighborhoods.

Lot by lot, the planned freeway path became a vacated strip of wasteland. Property values plummeted, as houses sat abandoned awaiting demolition. Yet decades passed before the freeway was finally built. Opening in 1995, Highway 180 established the Lowell Neighborhood’s triangular shape, with the new northeast-southwest freeway boundary intersecting the commercial corridors of Blackstone to the east and Divisadero to the south.

The isolated neighborhood became impoverished and a hotbed for crime. Further undermining the community, cutthroat developers labeled the Lowell “The Devil’s Triangle,” in an effort to drive down property values. A flawed re-zoning policy allowed concentrated poverty to flourish, as single-family residential zoning was changed to multi-family zoning. Two-story, utilitarian apartment complexes, boxy in form and stripped of ornamentation, turned their backs to the streetfront. The monolithic structures were foreign to the surrounding turn-of-the-century architecture.

The transient dynamics of the neighborhood promoted gang activity and hostility through the ‘90s and 2000s. By then, literally all the homes in the Lowell were converted to multi-tenant residences. Trap houses were a dime a dozen, streets and sidewalks were no longer maintained, overgrown trees grew rampant and lampposts were either broken or blacked out.

Oscar Rodriguez remembers those days. He used to destroy his neighborhood. Now he puts in every effort to make sure that isn’t an option for future generations. As Martin Park’s program director, Oscar facilitates a safe place for youth. He inherited the historic home and grounds from Dr. Marty Martin, a transplant from a more upscale part of town who came to serve and bring positivity to the neighborhood. Dr. Martin told him one thing, “The yard comes with kids.”

Oscar has been running Martin Park for six years. The organization has steadily built partnerships and streamlined assistance over its two years of 501(c)(3) status. Donations help with improvements and resources for education and activities, but there is always a need. Landscape architect Terry Broussard is helping to better organize outdoor spaces along with his wife Kim, who is improving how interior spaces can better serve the program. They hope to mitigate nuisances, such as baseballs breaking windows, establish outdoor gathering spaces, and give Oscar and his family some privacy when needed.

Martin Park is a prototype. Oscar is planning a similar park in the area, using Martin Park as a model. He hopes to bring this typology to every needy neighborhood in Fresno and throughout the Central Valley. When schoolyards close for the evening and malicious activities are prominent in neighborhood parks, Martin Park always has its gates open. In the Lowell, Oscar Rodriguez is flipping kids, not houses. Oscar hopes to empower them with the values they will need to be able to stay in the neighborhood they grew up in.

With government-assisted housing no longer offered in the neighborhood, residents are being displaced. Revitalization is well underway, yet pockets of struggle still remain. What is allowing the neighborhood to continue to thrive?

To find out, I visited with Dr. Don Simmons, whom I had met while volunteering as a Historic Home Tour guide. A Fresno Historic Preservation Commission member, he’s been a resident of the Lowell since 2005. Simmons voiced how the way we designed neighborhoods pre-war was fundamental to establishing the tight-knit social fabric that still exits today. Walkability, public-transit, large porches, and facades addressing the streetfront are key design features of the neighborhood. Architecture and design in Fresno’s early history were nothing less than superior. Architects from MIT, Berkeley, and the Ecole des Beaux Arts all came to build in Fresno during the city’s infancy. Even works by Julia Morgan border the Lowell.

While lounging on Don’s porch on a summer afternoon, I noticed how well this semi-public space functions. A “third space” is what he calls it. Not public, nor private, but an extension of both. A space that all residences have in common. From the porch, you can converse with passers-by, shout to neighbors across the way, all the while maintaining vigilance over the street. Human-to-human interconnectivity is the primary design intent of the Lowell. The car is secondary, just as horse carriages were. (And, yes, there are a few carriage houses and hitching posts in the North Park area of the Lowell. Garages, not so many.)

A design review committee has existed for the neighborhood since 1991. Recently, the city adopted the Downtown Neighborhoods Community Plan. The new design guidelines value original neighborhood design features and call for their implementation in new construction. For example, between Fulton and Van Ness Avenues stands The Georgia, a new two-story, 24-unit community comprised of three buildings. Working as a designer for Paul Halajian Architects, who designed this project, has given me another vantage point for understanding the Lowell. At a glance, the street-facing façades seem just like any other house with a porch out front. The neighborhood context is recalled in elements drawn from both mid-century brick urban buildings to the south and Craftsman homes to the north, brought together with contemporary forms.

As much as I enjoy and value the abundance of pre-war residential architecture and a few recent examples of good design in the Lowell, I am remain particularly intrigued by Martin Park: a public space made not by architects or city planners but by children stumbling upon a place to play. The park, nestled among a few homes, is a protected environment, safe under the watchful eyes of neighbors two stories above and all around. And the carport is now the hearth of this community.

It is apparent that good design is one source of the good things happening in the Lowell today. As architects we must not forget that we design for people’s needs. Needs change over time, and the spaces we create will be made to suit, as has been the case with Martin Park. We should design with flexibility in mind; it may be the most sustainable way to build, contributing to the longevity of the places we touch.

Author’s note: my primary source for the history of the Lowell Neighborhood is the City of Fresno’s North Park Survey: Historic Context & Survey Report, Galvin Preservation Associates Inc., 2008.

Andres Diaz, Assoc. AIA, is a co-founder of DESVGN and Class Vl of the Downtown Academy. He is a designer at Paul Halajian Architects and a member of the arcCA Digest editorial board.

From arcCA DIGEST Season 1, “Housing.”