In 1993, I traveled to León, Nicaragua, out of a longing to put into action the idea that architecture has an important social role to play in the developing world. I began working with the New Haven/León Sister City Project to develop a program to build projects essential to the development of rural and urban communities.

The first project was a renovation for Proyecto Mujer, a nongovernmental agency working with women in prostitution, young women at risk, and their families. We worked with the women, side by side, for a month that summer, repairing the roof on their building and planning for additional renovations the following year. We brought two groups of volunteers from the United States, all eager to learn about life in Nicaragua and to make a difference in the lives of the people. We helped the women of the community work together as they learned to use hand tools and to mix cement and adobe plaster. The women were restoring the building as they restored their lives.

By 1995, we began working directly with rural communities that are among the poorest in the hemisphere. While details of each community vary, the level of need was characterized not only by the absence of basic infrastructure, such as potable water, electricity, and transportation, but also by lack of access to education, jobs, adequate food, and health care. The quality of self-built housing also contributed greatly to the average person’s struggle to remain healthy, due to inhalation of smoke from wood fires, as well as from earthen floors that are a breeding ground for disease. This degree of poverty contributes to isolation and an inability for individuals to consider the future for their families and community, as they struggle constantly just to survive.

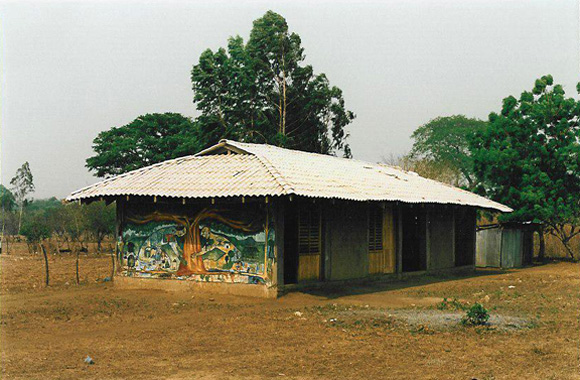

We created an egalitarian process for choosing which projects were of highest priority, structured to empower the community to make the final decision. It was the role of the community to identify shared problems and potential solutions. This process frequently resulted in the building of a small school as the first communal undertaking. It was substantial in scope, yet manageable, and could be funded over the course of construction. To fund the work, we made use of a great first-world resource—donated used clothing. The clothing was sold in the community to pay for construction materials. The first school was for Los Barzones, which had a population of nearly 100 families. We worked together for two years, bringing occasional groups from North America to build a rammed-earth building. As the school was going up, we began projects in other villages. In La Ceiba, we renovated an abandoned cotton-ginning factory; in Palo de Lapa, we built a concrete block addition to an existing pre-fabricated concrete school; and in Carlos Nuñez Tellez, we created a master plan for a lower and middle school, along with a medical clinic.

This Work Has Led To Several Discoveries and Conclusions:

Architecture is a vehicle for building communities. The reason for beginning a development project was not because we had a project we wanted to realize, but because there was a goal we wanted to achieve: community development. A project with this as a goal is evaluated differently. The project serves as a vehicle of empowerment. It requires community members to work together, learn new skills, and become better leaders. It also more fully reflects the aspirations and achievements of the community as a whole. The chosen project is often centrally located and provides tangible evidence of the hard work and vision of the community.

The Role of a Non-Governmental Organization is one of support. The role an NGO plays is to make available the resources needed for the project or to direct the community to an NGO that does. These resources may be financial, but most often are aesthetic and technical, such as architectural and engineering services; or material, like the clothing donations for the Proyecto Mujer project.

An architect and a rural community working together reveal the biases each has. This is perhaps most obvious in how well and with what a project is made. While I came to the communities with the intention of making earth buildings, believing they had a cultural tradition in this type of construction, they were convinced that concrete block was the best material to be used. We were both correct. There is a long history of adobe and earth plaster buildings in the region. Yet, the faster and potentially safer way to build is in concrete block. Nevertheless, rammed-earth continued to be an important construction method. We knew that experience in earth-building techniques is widespread in the León region and that there was an abundance of unskilled labor. We believed, therefore, that the construction would be better understood than an imported building system. We also wanted to reduce the use of industrial materials like concrete and non-renewable materials like wood.

The construction process itself is a shared patrimony. Many rural campesino families live in houses constructed of un-milled tree limbs assembled as a structural frame set in the ground, with roughly hewn lumber, plastic sheeting, or corrugated metal for siding, and unfired clay tiles for roofing. However, they understand communal buildings to be made of masonry finished with plaster, even though few have ever been involved in the construction of such a building. The result was that, by honoring their shared conception of the project and the degree of construction experience, the final projects were rough and irregular in the best sense of the word.

If the project is for the community, the community should build it. We learned at the beginning that there was a lot of labor available, and we had to involve community members or risk losing their support. Therefore, we tended toward building methods that were labor intensive and required little or no expertise. Concrete block turned out to be an occasionally useful method, but it requires only an experienced mason and a few helpers, leaving others with little to do. Rammed earth, on the other hand, requires many people to dig, sift, mix, compact earth, and collect water from communal wells. The crew needs no previous knowledge of construction. They can use materials and farming tools that are available on site. It is a system that can be learned in a morning’s work. The rammed earth construction also allowed the delegations from North America to join in the labor and experience the work first hand.

While schools continued to be built, by 1997 we began to develop programs that bring a greater degree of economic development to rural and urban communities. While it complemented our community development work, as a process it differed fundamentally from the egalitarian methods we had employed with the rural communities. We developed two programs.

One is a kitchen garden program that teaches school children to plant, tend, and harvest vegetables, using organic gardening techniques. It has led to a significant improvement in the nutrition of rural families, while providing enough surplus food to sell in local markets.

The other is ViviendasLeón, an urban housing construction and loan program. It arose partly out of a response to a 1992 United Nations study that identified overcrowding and a lack of access to credit as two of the principal barriers to development in urban León.

ViviendasLeón recognized that these problems could be overcome, given the unique circumstances in Nicaragua. In the 1980’s, the government had instituted a program of land reform. All citizens were given title to the land they had lived on for generations. Therefore, they owned the necessary equity for capital investment. The missing ingredient has been a banking system offering reasonably priced loans.

The lack of access to credit goes hand in hand with a lack of access to adequate housing. Loans are needed to finance construction as well as mortgages. The result is a situation in which highly trained professionals, who are critical to the rebuilding of the country, live in substandard housing, at risk of earthquakes, floods, and hurricanes. In 1972, Managua was literally destroyed by an earthquake. In 1998, Hurricane Mitch left thousands of León citizens homeless.

It was this situation that led to the creation of ViviendasLeón, a non-profit organization that offers short-term, low-interest, equity loans and builds safe and affordable housing for working professionals and their families.

To ensure the program’s success, ViviendasLeón has contracted with UNAN, the National Medical University in León, to build housing, to California building standards, for its teaching staff. In return, UNAN guarantees monthly mortgage payments by drawing directly from employee salaries. At the end of ten years, a home is paid for in full and ViviendasLeón has acquired a steady stream of capital for future development. At the current time, ViviendasLeón has the necessary infrastructure to build twenty houses a year.

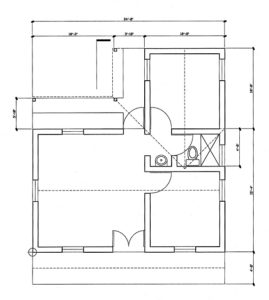

The houses employ elements found in existing colonial and rural architecture in the region, where interior courtyards are commonplace. The plan is an L, hinting at a future interior or walled garden. The house has a living/dining room, bathroom, and two or three bedrooms, which form the leg of the L. Kitchens are commonly found under a roof overhang.

Like the GI Bill that gave average Americans the ability to own a home and provided the engine for our own economic growth, ViviendasLeón’s equity/loan/construction program is designed to significantly contribute to the growth of the Nicaraguan economy. Equity investment leads to a stable middle class, in this case the medical staff of UNAN, who can, in turn, provide a safe and secure life for their families and continue their important role in building a stable and healthy society. ViviendasLeón is, therefore, both a business enterprise and an agent for social change that has created a fundamentally unique approach to development and serves as a development model for the entire region.

All images by the author.

Author Evan Markiewicz has been in non-profit practice since 1993, when he founded MakingGood, an organization that worked with social service agencies to improve conditions in homeless shelters in New Haven, Connecticut. The same year, he began working with the New Haven/León Sister City Project, developing construction programs for urban and rural communities in León, Nicaragua. In 1997, he began work on ViviendasLeón, an innovative economic development program that builds affordable housing and offers mortgages at affordable rates for working families. He continues to maintain a small professional practice in San Francisco.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2003, in arcCA 03.2, “Global Practice.”