This essay concerns the mobilization of the artistic community during World War II, not as expressed in the outraged imagery of a Guernica or a Heartfield montage, but through the direct recruitment of the applied arts—architecture, industrial design, and graphic design—by the Office of Strategic Services, America’s wartime intelligence agency. The artists drawn into the “Presentation Branch” of OSS entered the secret war with boundless enthusiasm, a determination to support the anti-Fascist campaign, and—like most other units of the fledgling intelligence service—no particular idea of how they were supposed to do it. Their early campaigns reveal the bravado of infinite possibilities. Gradually, as their ambitions became adjusted to reality, a series of theoretical principles evolved which enabled them to apply the scienza nuova of design to the ancient art of war. Through their pioneering experiments in the visual display of information in the propaganda war, in service of the War Crimes trials at Nuremberg, and, finally, in the waning months of the organization, in preparation for the founding conference of the United Nations in San Francisco, they left a small but indelible mark on history. Armed with this extra ordinary wartime experience, they went on to make a much larger mark on their respective professions.

The Office of Strategic Services

Overtaken by events, the United States found itself at the onset of the Second World War wholly unprepared in the field of intelligence. The Army and Navy maintained their separate military intelligence branches, the FBI dutifully carried out domestic surveillance, and a dozen other agencies conducted information-gathering activities of various sorts. No centralized intelligence service existed, however, that was capable of operating on the same level of professionalism as the British SOE, the Soviet NKVD, or the German Sicherheitsdienst. This failure has been explained by the legacy of post-Wilsonian isolationism, by a populist fear of an invasive secret police apparatus, and even by the patrician etiquette that dictated that “gentlemen do not read other people’s mail.”

Even before the attack on Pearl Harbor put an end to American innocence, President Roosevelt had taken the first steps to redress this deficiency. In mid-1940, he asked his friend William J. Donovan to undertake a series of overseas missions to assess the military situation and to evaluate American intelligence needs in what was shaping up to be a war of global proportions. On July 11, 1941, the President accepted Donovan’s recommendation that a “Service of Strategic Information” be created, and designated him the nation’s first Coordinator of Information.

Having virtually no precedent on which to build, the early history of OSS is that of an organization inventing itself. With remarkable boldness, Donovan recruited New Deal economists from Washington, Marxist philosophers from the German refugee community, socialite adventurers from the Ivy League, and a motley assortment of American labor activists, European Social Democrats, White Russian monarchists, and some two-hundred and fifty veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. “I’d put Stalin, himself, on the OSS payroll if I thought it would help defeat Hitler,” quipped the Republican Donovan in an unguarded moment. His wildly unorthodox conception of modern warfare led him, finally, into the shadowy underworld of art, architecture, and design.

“One Picture Worth a Thousand Words”

Influenced by the slick persuasiveness of commercial advertising, Donovan had, in his civilian law practice, frequently supported his arguments with arresting visual devices. Behind the battle cry, “One picture is worth a thousand words,” he vigorously promoted these practices in his new position as Coordinator of Information. Knowing that the President would be the focal point of an inconceivable volume of information, he allocated a remarkable 24.9 percent of his first annual budget toward the design of visual presentations. How could the latest techniques be applied so as to enable the President to absorb, in a one- or two-hour, multi-media briefing session, masses of intelligence data that, in written form, might take months to assimilate?

* * * * *

This question set in motion an alliance, which was sustained throughout the war, between the infant intelligence profession and the only slightly older profession of industrial design. In search of “the inventive genius and the technical creativeness of the country’s best engineers and industrial designers,” negotiations were opened with the offices of Raymond Loewy, Walter Dorwin Teague, and Henry Dreyfuss who, flushed with their triumphs at the 1939 World’s Fair, signed on as Expert Consultants in September. The visionary Norman Bel Geddes was taken on only when the job was fairly well-defined “so that Geddes wouldn’t start moving mountains.” They would be joined, at this early stage, by the inventive Buckminster Fuller and architects Louis Kahn and Bertrand Goldberg, each of whom had been experimenting with prefabricated, mass-produced housing units. Lewis Mumford, fresh from the anti-isolationist polemics of the day and anxious to play some part in the war, contributed his ideas, as did his friend, Lee Simonson, the theatrical designer, as well as the greatest visual communicator of them all, Walt Elias Disney. The language of theatricality—not surprisingly—pervaded their far-reaching discussions.

* * * * *

In Never Leave Well Enough Alone, that masterpiece of unabashed self-aggrandizement, Raymond Loewy recalled how, when the war broke out, he loaned Donovan “one of my most brilliant young men [who] became one of the top men in the Department of Visual Presentation.” The “brilliant young man” whom Loewy did not trouble to name was Oliver Lundquist, a prize-winning architecture student at NYU and Columbia who had been working for Loewy as a specialist in industrial and product design. Lundquist began to do consulting work for COI during the summer of 1941, and moved to Washington on a full-time basis in October. His first assignment was to design statistical charts reflecting Soviet economic capabilities. This seemingly mundane task proved to be a key element in the decision to continue the Lend-Lease program in the face of conventional military wisdom that held that a German victory in Russia was inevitable. It also suggests the imaginative approach that OSS applied to the new art of “envisioning information.”

Shortly thereafter, another architect, Donal McLaughlin, left the artful world of the New York designers for the more sober demands of a world at war. A product of NYU, the Beaux-Arts Institute, and Yale, McLaughlin had worked with Teague on exhibits and dioramas for the 1939 World’s Fair. In the spring of 1942, McLaughlin moved to Washington and became Chief of the Graphic Section of the Visual Presentation Branch. Over the next three years, he built up a team of artists who illustrated film reports; drew charts, graphs, and maps; prepared technical illustrations of secret devices and weapons; made propaganda sketches, caricatures, and forgeries; and more.

They were followed by a growing staff—114 in all by the end of the war—of architects, industrial designers, artists, editors, illustrators, engineers, machinists, photographers, filmmakers, composers, economists, cartographers, psychologists, and even a historian. Eero Saarinen, already one of the most daring architects of his generation, had been smarting over the cancellation of a gigantic General Motors research center for which he had the contract— and from the arrival of his draft notice—when he received a call from his former Yale classmate, McLaughlin. In OSS, Saarinen became Chief of the Special Exhibits Division, with responsibility for all three-dimensional projects. Jo Mielziner, who by 1942 had designed more than 150 stage settings for New York theater, opera, and ballet productions, became Chief of the Design Section. Walt Disney sent over a couple of animators; and the editor of the Viking Press, David Zablodowsky, came on board to direct the Editorial Section.

Other people were drawn into the organization at early stages of careers that would blossom after the war, often on the basis of the multidisciplinary, multimedia hothouse experience of OSS. Edna Andrade went from graphics work in OSS to a successful career in the Philadelphia art world; and Alice Provensen as creator of the popular Golden Books series. Dan Kiley became one of the most celebrated figures in the modernist tradition of American landscape architecture. And Benjamin Thompson, who eventually would be awarded the coveted AlA Gold Medal for his campaigns to reinvigorate the urban life of Boston (Faneuil Hall), New York (Fulton Street Market), Baltimore (Harborplace), and Washington, D.C. (Union Station), acknowledged that the models and simulations he built during the war formed the basis of his later ideas about design and the communication of space and form.

Nor was this all. Georg Olden, who dropped out of art school to join the Presentation Branch, went on to become Art Director for CBS and is recognized as the first African-American to break through the color bar into the world of graphic design. Robert Konikow was drafted into OSS with a background in mathematics, but his experience in the Editorial Section redirected him into the world of communications and a distinguished career in the field of exhibition design. Paul Child was transferred from the Graphics Section in Washington to the OSS Outpost in Ceylon, where he prepared maps and other visual displays for the Far Eastern Theater. On the porch of a tea planter’s bungalow he met—and later married—fellow OSS officer Julia McWilliams. Reassigned to the OSS outpost in Chunking, they acquired a taste for Chinese cuisine and, in postwar Paris, Paul and Julia Child mastered the art of French cooking.

* * * * *

Visualizing Peace: San Francisco

By the beginning of 1945, the Presentation Branch was at work on a series of projects relating to the forthcoming United Nations Conference in San Francisco—films, exhibits, publications, lecture materials, a full range of graphic services, and the behind-the scenes tasks of “stage management” at which it had become so adept.

* * * * *

The San Francisco conference ran for two months, during which the services of the Presentation Branch were in constant demand. Architect Benjamin Thompson developed a system of flexible charts that enabled Secretary of State Stettinius, Foreign Ministers Anthony Eden and Vyacheslav Molotov, and South African President Jan Smuts to visualize the shape of the emerging organization and the shifting political forces it reflected. Oliver Lundquist, serving as “Presentation Officer,” together with Broadway theatrical director Jo Mielziner, designed the stage setting for the final signing ceremony; working through the night, Graphics Chief McLaughlin created a lapel pin for the members of the national delegations, with an azimuthal equidistant world projection that so deftly met the political and aesthetic requirements of the occasion that it became (and remains) the official seal of the United Nations.

Visualizing War: Nuremberg

The lessons learned in managing the historic San Francisco conference were applied with comparable effect to the trials of the Nazi leaders implicated in war crimes, crimes against humanity, and crimes against peace. In May 1945, as four occupying armies fanned out across a shattered Germany, the Office of the Chief Counsel circulated a memorandum to OSS outlining a comprehensive program “to demonstrate Nazi guilt clearly to the world.” The role of the Presentation Branch in this process would include the collection of evidence; the preparation of graphic materials for use in the trial briefs and during the proceedings; and the architectural planning and layout of the courtroom itself. Having won the propaganda war, and with the legitimacy of the tribunal at stake, the designers were now challenged to solve a barrage of technical problems in ways that did not compromise “its dignity, its dominance, or its authenticity.” Since the guilt of the accused was a foregone conclusion, the task of the designers, though never so bluntly stated, was to contribute through every means at their disposal to this inevitable outcome.

Concretely, this meant that supplementing the arguments of the American prosecutors would be a body of visual materials planned and executed by the Branch: detailed wall charts elucidated the political empire of Hermann Goering; photomontages exposed the functioning of concentration camps; exhibits represented the chain of accountability in the occupied countries; films were produced for use during the trials and as part of a coordinated program of public information. Justice Jackson’s opening arguments were supported by a six and one-half by fifteen-foot chart of the structure of the Nazi Party—“an intricate blueprint of the organization that wrecked Europe”—that was the product of six months of painstaking research by jurist Henry Kellerman of Research & Analysis and Cornelia Dodge, a twenty-four-year old graphic designer in the Presentation Branch. In Nuremberg, Kellerman reviewed the chart in the course of his interrogation of Robert Ley, who since 1933 had been the NSDAP Chief of Party organization. Ley, who once boasted that under Nazi rule “only sleep was still a private affair,” verified the factual accuracy of their work but pointedly objected that its two-dimensional graphics had captured only the static structure and not the “soul” of the movement. Two days later, as if suddenly grasping the implications of his criticism, he committed suicide in his cell.

For over a year, OSS had been closely involved in the preparations for the war crimes trials. By the summer of 1945, the Presentation Branch had worked out the basic architectural logistics of the proceedings: the positioning of the judges, witnesses and defendants; apparatus for the presentation of evidence; facilities for a press corps expected to number in the hundreds; and the outfitting of offices, barracks and prison cells. There remained only the pressing problem of siting, which was resolved in July when an OSS surveying team, headed by the landscape architect Dan Kiley, began to close in on the medieval city of Nuremberg (Nürnberg). “I wanted the Nürnberg Opera House,” Kiley recalled, “where we could have staged it in a very dramatic and thrilling way.” His dreams of a Wagnerian Gotterdämmerung were overruled, however, and the OSS designers team began work on the repair and retrofitting of Nuremberg’s imposing Palace of Justice.

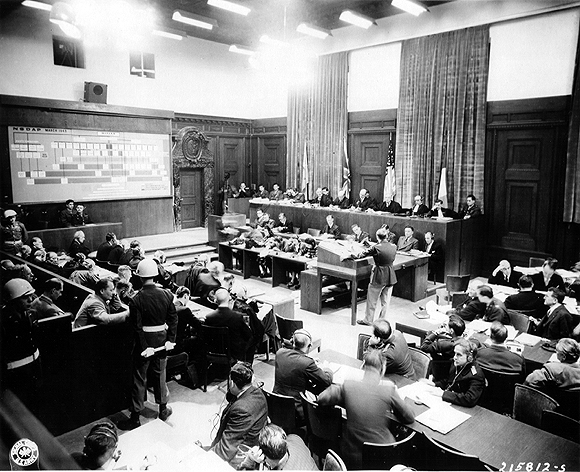

Having been influenced by the teachings of Walter Gropius at Harvard, Kiley set out to solve a simple problem of functional design, consistent with his brief that “there should be no allowance in design and layout for purely decorative, propagandistic, or journalistic purposes.” As the critique of the modernist project has, by now, long since demonstrated, there can be no design degré zero; and in the highly charged environment of Nuremberg, political symbolism was as much a part of “function” as were electrical outlets and a reliable public address system. This is most evident in the ultimate design of the courtroom, which placed the judges on high-backed, throne-like chairs, framed by their national flags, and towering over the twenty-one defendants seated directly across from them. On the side wall was mounted a large screen on which the record of Nazi criminality could be projected. A model was presented to Justice Jackson, head of the American delegation. “He instantly approved the plan,” recalled exhibition designer Robert Konikow, “appreciating the drama inherent in the face-to-face positioning of the defendants and the judges,” with the battling attorneys arrayed in a no-man’s land in between. With the physical site established, a team of Presentation specialists headed by David Zablodowsky was dispatched to Nuremberg, where they designed everything from wall charts to press passes. By the time the historic trials opened in November, however, the Office of Strategic Services—its spies, its intelligence analysts, and its designers—had itself become history.

On September 20, 1945, with the chill of autumn and the Cold War already perceptible in the Washington air, President Truman thanked General Donovan and his staff for their work and abolished the Office of Strategic Services. The reasons for this decision were complex, but its reputation for sheltering people “of progressive orientation,” as ex-Communist Carl Marzani discreetly put it, did not endear the OSS to other government agencies in the months when the shooting war against German Fascism was solidifying into a Cold War against Russian Communism. Yet, by the time of the U.N. conference and the Nuremberg trials, the services of communications specialists—once tolerated as “an expendable luxury”—had come to seem indispensable in the policy process.

Author Barry M. Katz, PhD, is Professor in the Visual Criticism Program and Industrial Design Department at California College of the Arts (CCA) and an IDEO Fellow at IDEO Product Development. His books include Foreign Intelligence: Research and Analysis in the Office of Strategic Services, 1942-1945; Technology and Culture: a Historical Romance; and Herbert Marcuse and the Art of Liberation. This article is excerpted from a more extensive essay, originally published in Design Issues, vol. 12, no. 2, summer 1996. It is reprinted by permission of the author.

Originally published 1st quarter 2005, in arcCA 05.1, “Good Counsel.”