In Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game, protagonist Ender Wiggins finds himself launched into deep space, charged with the task of defending humans from an intergalactic menace. Not content to stand by and do nothing while their brother saves the galaxy, Peter and Valentine Wiggins take it upon themselves to tackle a more terrestrial, yet no less difficult, challenge—preventing the next world war. Using the virtual communications network, “The Nets,” to educate themselves on world history, international politics, and even transportation and infrastructure networks, the Wigginses familiarize themselves with contemporary world politics. Once properly informed, they begin to self-publish their thoughts and concerns onto net discussion groups and private forums. Peter and Valentine are able to attract like-minded thinkers who respond and contribute to their ideas, eventually developing a dialogue having massive global ramifications. In this subplot of Ender’s Game, Orson Scott Card was essentially describing a vast and powerful network of political blogs and bloggers. It’s worth noting at this point that Ender’s Game was published in 1977.

To make sure we’re all up to speed here, let’s establish a basic definition for the term “weblog” or “blog.” Paraphrased somewhat, Wikipedia defines a blog as “a website where entries are commonly displayed in reverse chronological order, combining text, images, and links to other blogs, web pages, and other media related to its topic. Many provide commentary or news on a particular subject while others function as more personal online diaries. The ability for readers to leave comments in an interactive format is an important part of many blogs.”

With that taken care of, the question now remains, “What does this have to do with architecture?” For many people, the first serious exposure to architecture and architectural discourse doesn’t come until college, where everything seems to become suddenly accessible at once. The inner sanctum of academia offers its acolytes a well-versed faculty, lively peer groups, studios, histories, crits, discussions, and specialized libraries filled with vast collections of books, magazines, and journals. Views and opinions can finally take shape, technique is developed, and per haps the first signs of style begin to appear. Unfortunately for many, the last serious exposure to architecture and architectural discourse occurs when we leave that sanctum sanctorum. Today, thanks to the Internet, neither situation is necessarily absolute. From the comfort of their own home, a twelve-year-old French boy and an eighty-year-old Japanese woman can both learn about the history of architecture in Dubai and the importance of sustainable design in the desert. Like the children in Ender’s Game, they have access to a profusion of news, texts, films, photographs, and—most importantly—ideas.

Blogs are more than the rather static definition given above. They are a live, evolving network of individuals—an infinite classroom or endless studio full of not only architects, designers, artists, and critics, but also nurses, butchers, bartenders, and salesman. Each person has the opportunity to study industry-specific texts, to read first-hand accounts of incredible new works of architecture, and to add their voices to the chorus. With this kind of information no longer relegated to studio discussions and university theory seminars, architecture is becoming much more accessible to the public. Welcome to the blogosphere.

The Only Sure Things are Death and Taxonomy

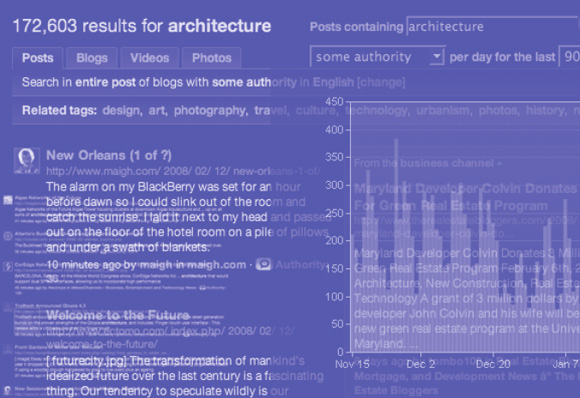

According to blog search engine Technorati.com, there are 112.8 million unique blogs as of January 2008, 5,405 of which are listed as relevant to “architecture.” That may seem like an inaccessible abundance of information, but blogs are nothing if not 1) specialized and 2) ephemeral. Readers quickly discover their preferred sites and visit them regularly, expecting new content. If it’s not there, readership diminishes until the blog drops off the radar—sometimes this happens after years of daily updates and regular maintenance. Demand for content is high, and as blogs are labors of love, those who write them are typically offered little reward besides the fleeting thrill of new comments, continual discussion, and the occasional fifteen megabytes of fame.

In this group of loosely affiliated, dedicated compatriots, there are as many different types of architecture blogs as there are architecture bloggers, and more are signing on (5,406…5,407…5,408…) every day. Content ranges from the super local (“I’m thinking about renovating my apartment…”) to the international; from adding new information multiple times a day to updating just once a month; from praising the work of emerging young architects to spreading the gospel of Rem Koolhaas—sometimes in the same post. Generally speaking, most architecture blogs can be collected into just a few basic categories, but with so many individuals creating unique content, the taxonomy becomes limitlessly idiosyncratic, reminiscent of yet another famous work of fiction, Borges’s The Analytical Language of John Wilkins. In this work, the author recalls some of the elaborate classification systems he has encountered; most notably, the “Celestial Empire of Benevolent Knowledge,” a system dividing animals into categories such as (a) belonging to the emperor, (b) embalmed, (g) stray dogs, (m) having just broken the water pitcher. Luckily, like-minded bloggers tend to attract one another. By sharing content, linking back and forth, and commenting on and creating responses to posts, informal networks of common interests are established. This drastically helps the reader distill those 5,405 architecture blogs, making it possible to find the desired type of content and avoid those blogs that in their eyes have “just broken the water pitcher.”

Just Please Don’t Call it “Blogitecture”

Take a photo, upload it, write a brief post or description, click “publish” and that’s it. Congratulations. You’re a published blogger. With publishing speeds like that, one needn’t wait until next month’s issue of (insert your favorite architecture magazine here) to get an update on that exciting new project halfway around the world—if there’s even room for it in that issue, of course. Returning to young Peter Wiggins, the prescience of Ender’s Game once again becomes clear. While speaking of his Net publication, Peter Wiggins describes—quoted here slightly out of context—what could be considered as one of blogging’s greatest benefits. “We can say the words that everyone else will be saying two weeks later. We can do that. We don’t have to wait.”

With the astounding array of content and an immediacy of distribution previously unthinkable, it’s now possible to follow almost any project from conception to construction. The instantaneity of publication means that an article doesn’t just cover a design when it is unveiled or a building when construction is complete. It has the power to grow and evolve with the project, making it theoretically possible to document the life of a building—from gestation to ribbon cutting to demolition—and share it with millions of people as it’s happening. Renderings and photos are published and republished, virtually dispersing around the world almost as soon as they’re made public. To anyone with an Internet connection, the discourse is open long before the doors of the building, and readers are on the inside right from the beginning, critiquing it and arguing every step of the way.

Comparisons have been made describing blogs as the modern equivalent to the small, often self-published architecture magazines of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Both serve as engines to further new and often radical ideas, featuring passionate authors sharing their ideas and their vision of how architecture could potentially improve the cities we live in, or even alter our landscape and shape the world around us. Such polemical projects and ideological stances are by no means foreign to the architectural blogosphere, but many blogs currently act primarily as news outlets that inject wit and opinion into their hyper-linked stories. As architecture blogs evolve, more and more may move from reporting and critiquing into actually producing independent work to support their ideas. There are already those that dig for deeper meaning, trying to understand an architectural work on a more conceptual level, so it’s not a stretch to envision a very near future where an affiliation of architecture bloggers—perhaps even an international online design collective—will become the next Archigram or Team 10. And who knows, maybe they’ll even achieve interplanetary peace in the process.

Author Jimmy Stamp is a designer with Mark Horton / Architecture in San Francisco. He has been publishing his architecture blog, Life Without Buildings, since 2004 and is a contributing editor at Curbed San Francisco.

Originally published 1st quarter 2008, in arcCA 08.1, “’90s Generation.”