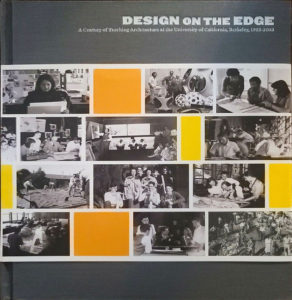

San Francisco: William Stout Publishers, 2009

From the edge, perceptions become amplified. This has certainly been the case when it comes to Berkeley’s College of the Environmental Design. One might argue that no school of architecture has been so identified with its location on the nation’s geographic and political spectrum. A handsome and thorough compendium, Design on the Edge paints a complex portrait of this influential institution.

The pedagogical contributions of the College of Environmental Design during the sixties and seventies are undeniable. The social, political, and environmental disciplines that it incorporated into architectural education are now being re-discovered, reconsidered, and reimplemented. It is, however, unproductive and inaccurate to define the school solely on these terms and by this era. Berkeley, an outpost that eventually became a touchstone in the national consciousness, struggled like other schools with tradition, history, the changing desires and values of students, the personalities of faculty, and the academy’s relationship to practice. Yet, there always seemed to be the pervasive sentiment that, distanced from the expectations of the East Coast academic hegemony, Berkeley was reinventing architectural education as it was inventing itself. A unique set of characters, from Bernard Maybeck to J.B. Jackson, and the democratic ideals engrained in California’s mythology—from the consistently high percentage of female students to the early introduction of open juries and free faculty/student dialogue—helped construct an architectural ethos that was inextricably interlaced with the sense of being on the western edge.

In the second two thirds of the book, the more recent intellectual concerns of the curriculum are described, usually firsthand by those who created it. In many ways, the pedagogical inventions of this period—from those planned, to those that were a response to local events that became national spectacle (People’s Park), to those accidentally stumbled upon (Sim Van der Ryn’s wonderful descriptions of his communal experiments in Inverness)— foreshadow much of the recent interest in design/build and sustainable communities. While some schools are finally taking these on, sometimes, as one takes a daily dose of Castor Oil, one understands how they have become germane to Berkeley. It is the latter part of Design on the Edge that holds the multiple overlapping, often contradictory voices that must have made for lively pedagogical debates and interesting faculty meetings. This latter part of the book includes seven sections, among them, “The Research Environment,” “Communities and Cultures,” “Ecology and Building Sciences,” and “Systematic Approaches.”

A section dedicated to the design studio is, however, conspicuously absent. Indeed, save for Dan Solomon’s erudite and entertaining article, the school’s influential design figures from the last thirty years (Saitowitz, Mack, Fernau, and others) are mentioned only in passing. This is a striking contrast to how the history through William Wurster’s deanship is told, with change and interdisciplinarity happening through design, not in spite of it.

As the editors note, writing a history of the period since the 1980s is difficult, there not being sufficient time for reflection. Accordingly, Design on the Edge feels more like a 75-year history than reflections on a century, and it misses the opportunity for the CED to show how its recent past, while much debated, is ready to be reshaped for a world engulfed in globally interconnected academic, architectural, and environmental exchanges. As Asia’s rise continues, Berkeley is clearly no longer at the edge. The natural question is, “Where does it go from here?”

Originally published in arcCA 10.3, “Design Education.”