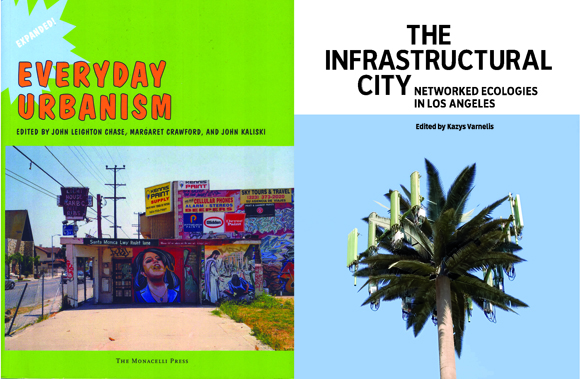

Everyday Urbanism. John Leighton Chase, Margaret Crawford, and John Kaliski, editors. New York: The Monacelli Press. 2008 (1999). 224 pp., illustrations, diagrams, and notes.

The Infrastructural City: Networked Ecologies in Los Angeles. Kazys Varnelis, editor. Barcelona and New York: Actar; Los Angeles: The Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design; New York: The Network Architecture Lab, Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, Columbia University. 2008. 251 pp., illustrations, diagrams, and notes.

Looking down on empty streets, all she can see

Are the dreams all made solid

Are the dreams all made real

All of the buildings, all of those cars

Were once just a dream

In somebody’s head

—Peter Gabriel, “Mercy Street”

The strange and unexpected forms our cities take as they transit from imaginings to realization and back again have given rise to a vast toolkit for apprehending such metamorphoses. Jonathan Raban’s soft cities within the hard, where bricks and mortar are psychically remolded by those who move among them; Henri Lefebvre’s spatial triad of perceived, conceived, and lived spaces continually reproducing and elaborating one another; Michel de Certeau’s restless, transformative practices of everyday life.

Ultimately, though, these constructs are high abstractions, and must be grounded in the pragmatics of nuts, bolts, and human hands if they are to be of use in understanding the making of real cities. The recent release of two edited volumes, The Infrastructural City and Everyday Urbanism, provide just such concrete grounding. The Infrastructural City is comprised of illuminating—and even delightful—chapters on the evolution of assorted infrastructures thought of as idiosyncratically contingent histories of personal and institutional practices. By way of example, in a handful of pages, one chapter deconstructs the very notion of traffic, while providing an overview of the development of traffic control from a policeman at every intersection to remotely sensing control rooms buried deep beneath our city halls. Another standout is an account of pavement—and of gravel in particular—focused as much upon the voided pits its mining leaves behind as its redistribution to form our hardscapes. And anyone who has marveled at how L.A.’s streets are simultaneously de facto research stations for botanical exotics will find much to absorb here, in the immigration histories and likely futures of eucalyptus and palm trees (both the vegetal and the telephonically cellular variety).

At the same time, there are chapters that, while exploring novel and unfamiliar infrastructures, are weakened by insufficient sourcing and by polemical criticism of our more destructive habits. Such criticisms at times appear as opaquely phrased moral pontificating that blunts both their impact and the accounts of the infrastructure to which they are saddled—as in an otherwise perversely fascinating depiction of the super-distribution centers for retail giants like Ikea and WalMart scattered about L.A.’s furthest nether-regions.

Nonetheless, the volume’s repeated observations that our infrastructures are reaching their limits, or are well past them, are well-taken and provide something of a unifying theme. This cautionary—at times verging on apocalyptic (we Angelenos, it seems, are never truly satisfied until we’re seeing our own city fall catastrophically in upon itself)—thread runs through most of the essays: the city’s infrastructure is devouring itself and everything around it, including the urbane lifeways it is intended to enable. An important theme, to be sure, although many of the authors are so intent upon telling the tales of their chosen piece of the infrastructural puzzle, and telling them well, that they seem to run out of space for this message. In the process, it frequently feels tacked on, sometimes only in chapter conclusions that are themselves little more than afterthoughts.

While the essays in this volume concur on the larger picture, they often vary widely not just in character but also in analyses that become, at times, glaringly dissonant. For instance, is the grade-separated Alameda Rail Corridor, recently created to carry high volumes of containerized traffic unimpeded from the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles, a new economic lifeline for L.A.? Or was it obsolete as soon as it was completed? There seem to be as many opinions as there are authors addressing it. Such disagreement underscores both the diversity of perspectives and the larger point that even the most Pharaonicly planned and constructed infrastructure yields uncertain outcomes. So it is that The Infrastructural City injects us from many points into the kluged-together organs and systems comprising the Frankensteinian body of the L.A. hyperregion, its ever-lengthening tentacles stretching the city’s paved plains and crumbling hillsides into distant lakes and deserts.

Everyday Urbanism, a decade-old book now augmented with updated material, is a collection of two sorts of essays. First, it is a compendium of thoroughly illustrated cases wherein the varied conditions and responses of everyday life have remade the city adaptively, contingently, and messily. Such cases span a wide range of scales, from the signage on a chainlink fence and the social ecology of a single alley to a typology of ever-metastasizing pod-malls. And, second, these cases are conjoined to cautiously formulated and thoughtfully presented heuristics (never algorithms or prescriptions) for how to work with such everyday dynamics. These heuristics are consistently given concrete illustration, by such potential (and, in a few instances, realized) projects as street vendors’ furniture, pocket parks that harmoniously accommodate existing neighborhood constituents regardless of their officially sanctioned “desirability,” and retrofits of entire urban districts sensitive to their initial conditions. Everyday Urbanism is thus a detailed recognition of everyday lives as the vectors along which city planning and urban design should proceed; simultaneously, it is an idea book for the objects and spaces such planning and design can create.

What Everyday Urbanism is not, contra some earlier critics, is anti-planning. Rather, it is critical of a particular, dominant kind of planning, whether in its High Modernist slash-and-burn or kinder, gentler, New Urbanist manifestation. Everyday urbanism objects to any planning that regards what is as a blight better replaced with a new, tidy, and commonly air-dropped master alternative—an alternative, it must be added, that is almost invariably exclusive in its realization. As such, while this volume is not committed to a countervailing planning solely for the poor and disenfranchised, it does give their concerns and practices at least equal weight. All urbanites, after all, are creators of everyday urbanisms.

These strengths, however, apply nearly as well to the original edition of the book as to the current version. More space given over to updated material, especially in the form of current commentaries on the older chapters, would greatly enhance this re-issue. Now that many of the realized everyday urbanist projects, new at the time of the original publication, have been in use for as long as a decade, it would be invaluable to revisit those projects and see how they have fared, lived up to expectations or not, and been transformed through their daily inhabitation. That, after all, is what an everyday urbanism is all about, and we can only hope we will not have to wait for a third edition in another ten years to find out.

If there is one overarching theme to Infrastructural City, it is that everything from watersheds to cellular phone towers have arrived at their ultimate dispositions through processes of everyday use and incremental transformation. This even in the presence of intensive, technocratic administration and despite planners’ constant efforts—and all the more now that so much infrastructural production and maintenance is left in the unsteady, invisible hands of the market. Given which, it is long past time we accepted Everyday Urbanism’s admonition that messiness, happenstance, and the unintended consequences of history accreted upon our streets are not aberrant blights to be extirpated, but inevitable givens and even opportunities to revel in and build upon.

Further, while these volumes focus on Los Angeles, they are at heart books about the urban, broadly understood. Circumstances conspired to ensure that I carried them with me through roughly half a dozen cities over the past couple of months, reading all the way. In the process, it became evident that, while L.A. may be exemplary of the dynamics presented across these pages, it is in no way exceptional. Rather, the analyses and analects to be drawn from these books are no less applicable to London, Tokyo, and a host of cities in between. As such, these volumes yield inclusive and flexible ways of looking at, and grappling with, our densely packed and overstretched cities in general. Perhaps most importantly, they remind us of a vital truth too often lost amidst our naturalized urban environments and their domesticated technologies: infrastructure is people.

Reviewer Steven Flusty is an L.A. geographer temporarily exiled to the Provinces,where he serves as an Associate Professor of York University. His primary obsession is the everyday practices of global formation, a topic he has interrogated most ruthlessly in De-Coca-Colonization: Making the Globe from the Inside Out (Routledge, 2004). His work has appeared in assorted electronic media and academic, professional, and popular journals of varying degrees of repute.

Originally published 4th quarter 2009 in arcCA 09.4, “Infrastructure.”