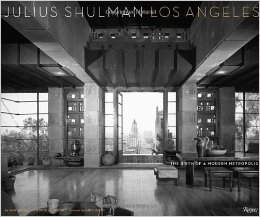

A handsome new monograph of renowned photographer Julius Shulman wisely lets the artist’s photos tell the story not only of the man, but of his adopted home of Los Angeles. Subtitled The Birth of a Modern Metropolis, the book begins with a brief introduction by Shulman’s daughter Judy McKee describing the man, followed by author Sam Lubell’s essay describing the myth. With the stage succinctly set, the remainder of this hefty publication showcases five themes—City, Development, Houses, Living, and Work—in striking, large format images from the 1930s through the 1960s, Shulman’s heralded purple patch.

Authors Lubell, west coast editor of The Architect’s Newspaper, and Douglas Woods, book dealer and private librarian, had unprecedented access to the Shulman archives. The result is a convincing attempt to broaden the understanding of Shulman as a photographer and Angeleno first, trendsetter and marketer second. Given that his reputation has been carefully curated over decades by the photographer and his editors, reshaping our contextual understanding of his work is not an easy task. However, because control of image was so important to both Shulman and a marketable Los Angeles, the authors contend that he truly was the right person for the time and place.

Julius Shulman is best known for using his talents for photographic narration to bring mid-century modern architecture into America’s collective consciousness. In the process, he became integrally linked with the burgeoning Southern California design style—and lifestyle. His photographs of the time not only document building and place, but also capture idealized character so deftly that the distributed image overshadows the physical reality. McKee notes that, “Julius incorporated this new architecture with his optimism and wonder to amplify his mythology of Los Angeles as a city where anything was possible.”

With camera in hand, Shulman moved from the farms of Connecticut to the streets of Boyle Heights with his family at age ten. With him, he brought his interest in the natural world, which, according to McKee, he never lost. Shulman saw humans as protagonists in nature. Mid-century urban Los Angeles was a tentative living organism set within the host body of the vast landscape surrounds. The rural scenes in the “Development” section of the book are revelatory, clearly showing humans “perched at the edge of civilization,” as an astute caption explains. Vistas and landscapes set the stage, delineating a mannered context in the artist’s pursuit of the ideal image composition and story.

The post-war culture of experimentation reinforced Shulman’s confident outlook. Lubell observes that, at this time, “Los Angeles, while by no means newly established, was transforming at breathtaking speed from a second-tier city into one of the largest metropolitan areas in the world.” Man and city went through adolescence together, with their idealistic dreams intertwined.

“Ever the salesman,” Lubell explains, “Shulman prided himself on portraying the city and its buildings in their best light . . . . For both business and personal reasons he had little interest in exploring the dark side of L.A.” Many photos in the “Work” and “Living” sections of the book are the result of more prosaic assignments commissioned by corporations such as Gypsum Associates or for trade publications like Country Gentleman. Hence, many of these images are unconvincing as documentation of typical Southern Californian lives, but do produce a fascinating study of what the promise of “typical life” in paradise was for Americans at the time. The most telling photo occurs even before the title page: an image of Shulman propping up a tree limb to frame a photo taken of a house in the dry California landscape. Sometimes reality needs a boost.

Also in the prologue images, there is a proof of the urban fabric with crop marks penciled in. More such images might allow us to better understand not only Shulman’s eye, but also how he wrote his stories. The authors do not claim to be comprehensive in their efforts, however; that is left for another brave soul. Rather, Lubell describes this book as “a guide to the spirit of a truly unique place: the life’s love of a person who has fundamentally altered L.A. as he captured and changed it forever.”

The opening essay includes a reference to Susan Sontag’s comment that a photo is like a slice of time. David Hockney’s proposal from his classic essay “On Photography” may also be appropriate here: “We’re always looking with our memory, as memory is always present. Memory is a part of vision—it’s inescapable.” In the pursuit of clearer insight into Shulman’s career as a photographer and Angeleno, the authors have succeeded in demonstrating how this artist did more than document Los Angeles. He created our memory of it.

Leigh Christy, AIA, LEED AP, is a freelance writer and Senior Associate at Perkins+Will in Los Angeles. She is also adjunct design faculty in the Interior Architecture Department at Woodbury University and led the Piggyback Yard Collaborative Design Group.

Originally published 1st quarter 2011, in arcCA 11.1, “Valuing the AIA.”