Cultural Context

In 1988, the death knell for postmodernism in architecture was rung by the Museum of Modern Art’s “Deconstructivist Architecture” show, curated by Philip Johnson (ironically) and Mark Wigley. Exhibitors included Peter Eisenman, Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, Daniel Liebeskind, Bernard Tschumi, and Coop Himmelb(l)au. Most of the old guard discounted these works as mere gallery products, while students consumed them with gusto, examining the application of structuralist and poststructuralist theory to architecture. Twenty years later, the roster represents some of the most prominent international architects of our time.

In 1989, architects Liz Diller and Ric Scofidio launched the multimedia installation “Para-Site,” also at the Museum of Modern Art. Neither the art nor architecture world could come to terms with this museum-wall destroying episode. Art critic Roberta Smith, writing in the New York Times, blasted the work as “slick, over-done,” and derivative. Diller Scofidio, better known then for temporary installations questioning cultural verities, would continue to struggle for acceptance. Even in 1993, New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp would use the platform of the paper to urge the intellectual pair to “Take the plunge. Down the hatch…to focus on more enduring projects.” Nearly two decades later, Muschamp’s wish was realized with Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s Institute of Contemporary Arts in Boston and other major commissions.

During the late ‘80s, artist and architect collaborations were very much in vogue, although most projects merely reflected introductory dialogue between the disciplines. Nonetheless, the curiosity and “cool” created by the union of the rock stars of both disciplines were too attractive to resist. In 1990, artist Barbara Kruger created the now iconic work, “I shop therefore I am.” It put a magnifying glass on the commercialism and excess of the 1980s and, together with the maturing works of Jenny Holzer and Cindy Sherman, heralded a more politicized art world. The three women’s work also resisted any need for architectural armature; the existing context provided the frames. The number of prominent collaborations dwindled as the country headed into a major recession and a period of introspection within the architecture community. No one shouted any battle cries, but in architecture schools across the nation, faculty and students were trying to sort out their paths after the rollercoaster ride from postmodernism to deconstructivism to a free-for-all.

The Academy

Bernard Tschumi took over as dean of Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation in the fall of 1988. Immediately, the halls were abuzz with the launch of the “Paperless Studio.” Computers were set up with the latest software. Evan Douglis, current chair of undergraduate architecture at Pratt Institute, recalled the impetus at schools experimenting with the new language and technologies. “They were playing a Piranesian game of how you access it, not how you build it. The old guards were struggling to figure out a way to critique the discourse, but the traditional language was not nimble enough.”

A popular Columbia anecdote of that time recalls a review in Hani Rashid’s studio. Steven Holl was one of the critics. The student work consisted mostly of blueprint paper “drawings” created by forms exposed in the sun. As the first student began his presentation, Holl asked if the drawings were of any scale. When the student responded with a definitive no, Holl took a look at his watch and excused himself, remarking: “Sorry, I got to go.”

Doris Sung, a 1990 Columbia graduate, relates another telling episode. A housing typology studio was traditionally offered in the second year of the M. Arch. program. 1989 marked a significant shift for the curriculum, as half of the studio rebelled against the faculty and rejected the imposition of typology in the studio. Their petition met with welcome from a supportive dean, who was seeking to push a series of changes at Columbia.

Upon graduation, Sung would return to a depressed job market in Los Angeles, where she found the shuttered doors of Morphosis, as Thom Mayne and Michael Rotondi sorted out their separate ways. If there were work at high profile offices such as Frank Gehry’s, the pay would not sustain a young graduate burdened with student loans.

Having exercised her critical faculty with an undergraduate liberal arts education at Princeton, Sung was attracted to the articulate and intellectual tongue of Liz Diller, a frequent critic in Stan Allen’s studio at Columbia. Diller Scofidio was a visible model of an “alternative” practice, setting one foot in architecture and the other in art. The sensual prosthetic devices featured in the pair’s early works had a definite feminine and intimate appeal to the young graduate, who would continue in subsequent years to explore notions raised by Diller’s works. Sung would also continue to utilize academic grants to support her critical, research-based practice and teaching activities, as had Diller.

Downtown at the same time, the Cooper Union did not embrace computational technologies. Under the leadership of John Hedjuk, it continued to ground the curriculum, as Douglis puts it, “in a literary, modernist, formalist agenda.” Influenced by Aldo Rossi, Raimund Abraham, and Hedjuk, the Cooper Union applied a narrative approach to “carrying out ethical, cultural investigations.” Studio programs with titles like “Available Light,” models of tortoise shell-inspired constructs, and drawings in the manner of Walter Pichler offered a snapshot of the phenomenological studio investigations.

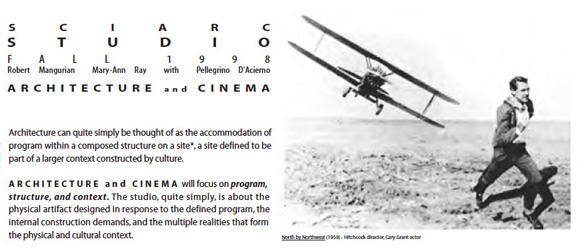

Across the country at SCI-Arc, “making and meaning” continued to be an important tenet pushing through from the late ‘80s. Tom Buresh taught an ethical approach to architecture steeped in material investigation. Perry Kulper investigated architecture as phenomenon, creating one landscape drawing each day. Across the hall, Robert Mangurian and Mary Ann Ray encouraged students to stretch their imaginations with studio programs that combined literature, fine arts, cinema, and photography with architecture. The intent was to help students develop generative tools and utilize the world around them as an infinite classroom. Synchronous teachings in Margaret Crawford’s classes theorized “architecture of the every day,” akin to the ethical cultural agenda of Cooper Union.

While computers were beginning to creep into SCI-Arc studios, drawings such as axonometric and perspectives were still popular and expedient tools of discovery and expression. Ray recalled two SCI-Arc fund raising auctions of drawings made by architects during the early ‘90s. Drawings by the likes of Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, Holl, Rossi, Gehry, Thom Mayne, Michael Rotondi, Tadao Ando and Michael Graves fetched significant sums for the school. Even a letter from Philip Johnson, stating he could not do a drawing for the auction, was sold. In New York City, Max Protech Gallery continued to sell architectural drawings as exalted artistic commodities at a brisk clip.

As the economic recession restricted the availability of work for early ‘90s graduates, many sought work in cities abroad. Paris and Berlin were popular destinations for those who could muster funds to travel to the doors of foreign architects. Other innovative individuals would see another way of establishing practice and surviving the depressed marketplace closer to home. The HEDGE Design Collaborative, a group begun in 1995 by several SCI-Arc graduates, included designers from Canada, Japan, and the United States. The diverse interests of the collaborative included architecture, interior design, landscape design, and urban projects, as well as graphic, website, clothing, and floral design. Their website expressed the sense of expanded potential in this communal arrangement: “Overlapping design priorities have emerged repeatedly in dialogue between members and in the execution of work. Direct engagement in construction and manufacturing, new material research and experimentation, and the re-adaptation of ready-made technologies all factor into many HEDGE projects, as do our interests in branding, identity, signage, and street dynamics.” Other alternative and hybrid models of practice included Mimi Zeiger’s (SCI-Arc) Loud Paper magazine and Garrett Finney’s (Yale) work as an architect for NASA.

The ‘90s generation acquired facility with emergent spatial modeling and rendering software, both as generative and representational tools. The entertainment industries desired their skills; credits on films such as The Matrix include architecture graduates. Comfortable with the software, young graduates also began to question its limitations. As a young instructor, Douglis explored those limitations. He researched and tested generative design and manufacturing technologies, through the lens of architecture. This trajectory continues in his current practice and in the curriculum at Pratt, where programming classes challenge the limits of software.

CNC milling and 3D printing technologies became attractive tools for young graduates eager to realize in physical form the non-orthogonal work they designed in school. Economical reality pushed some to become providers of fabrication and construction services, as they continued to develop their own, often noncommissioned works.

A significant number of graduates have returned as studio instructors, modeling themselves at times after their mentors. Theoretical pursuits highlighted by instructors such as Eisenman left graduates yearning for engagement they could not find in traditional practice. In the academy, they can pursue expanded possibilities of practice, as well as stay engaged with critical discourse and research. This ‘90s generation will continue to shape education as they encounter society under the rubric of architecture.

Author Annie Chu, AIA, is a principal of Chu+Gooding Architects in Los Angeles, focusing on projects for arts-related and higher education clients. Clients include Museum of Contemporary Art, The Hammer Museum, Kentucky Museum of Art+Craft, UC Riverside, LA Philharmonic Association, Getty Center, and Southern California Public Radio, among others. She is a member of the arcCA editorial board and the AIA Interior Architecture Advisory Group.

Originally published 1st quarter 2008, in arcCA 08.1, “‘90s Generation.”