Excerpts from a Conversation Convened and Moderated by Peter Zellner

Given that architecture may be considered one of the few forms of cultural production that leaves a lasting imprint on the physical, social, and economic environment, what are some of the goals you have established for your practice relative to the notions of innovation, contribution, and legacy? If there was one thing about architecture that your practice might change (even slightly) through its own evolution, what would that be?

Lloyd Russell, AIA, San Diego: Meaningful architecture is the expression of the sum of forces that bring it into being. The goal of my practice is to express exactly the unique condition that arises from combining the roles of architect, developer, and contractor. A city built by enlightened developer-contractor-architects is my definition of utopia. I hope my practice and teaching get us a little closer.

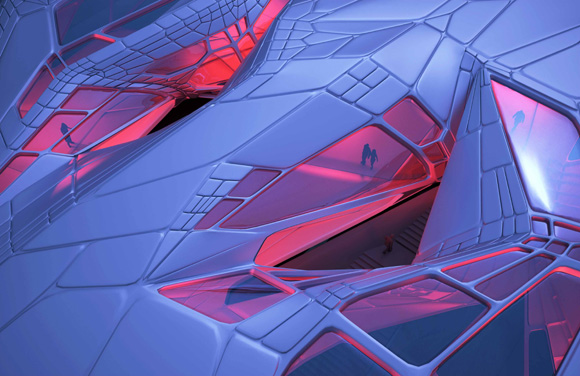

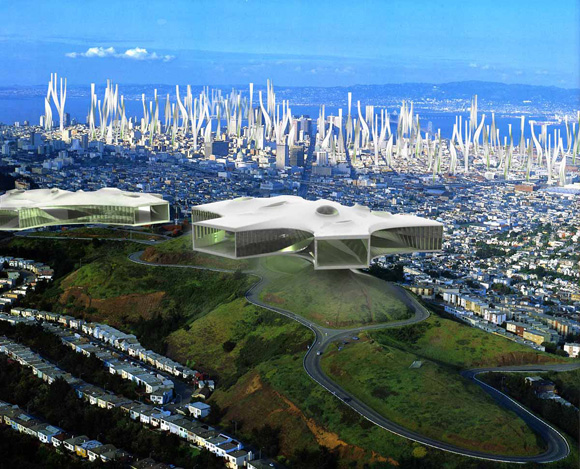

Tom Wiscombe, EMERGENT, Los Angeles: I am getting more interested in dealing with energy in terms of design. The trick is to avoid formal assumptions about “green building” and move on to more inventive territory. “Energy performance” is starting to breed a new functionalism, which would be a huge step backward. The next generation of digital production will involve more sophisticated tools, such as true physics simulators, which have the capacity for optimization feedback loops. This has begun to happen with the so-called BIM revolution, which is not a revolution at all but an inevitable expediency. At the end of the day, it is in the realm of design that architects are the most productive, and I am committed to that above all.

Joe Day, Deegan Day Design, Los Angeles: Almost all of us oscillate between the pure and the provisional—between speculation and realization, but also between the ideal and ad hoc. I don’t feel like a guerrilla, doing daring work against long bureaucratic/capitalist odds, nor like part of a movement pioneering a field of digital possibility. My goals are modestly Duchampian—as he put it, “mediumistic”: to elucidate the mechanics of our discipline and its impact on cities, in the hope of sensitizing more people, more acutely, to their environment.

I feel as I imagine Duchamp must have, arriving in Paris after his two older brothers had already immersed themselves in Cubism. All the serious positions in advanced abstraction had been staked out, but no one was weighing the avant-gardes against one another or doing work that “stripped bare” their techniques enough to invite a public into dialogue.

Advanced architecture is at a similar moment of intense but deeply self-regarding innovation, and almost all of the nuances we fret over are lost on a broader audience. I’m not interested in refuting those advances, but in doing work that opens them to and challenges them in a wider arena.

Rene Peralta, generica arquitectura, Tijuana: There are so many possible futures, since my firm is engaging in writing, film, and architecture, all strategies to survive as a young practice. Theory plays an important role: Canclini’s hybridity, Koolhaas’s generic city, De Cauter’s heterotopias, and other contemporary urban and cultural conditions. I have been adjusting to an alternative practice due to my “positioning” on the border. Our contribution differs drastically as we move between San Diego and Tijuana. To the north, we intend to stimulate a discourse, while in the south it’s all about tactics (architectonic and urban) that deal with the volatile process of change.

Teddy Cruz, Estudio Teddy Cruz, San Diego: I think of the political as a process by which we expose power: Who owns the resources? Whose jurisdiction is it? Who profits? Can a neighborhood be a developer? One example: in San Diego’s most successful recent building boom, not one affordable housing project has been built in some of the depressed neighborhoods. Why? Because to be competitive in terms of tax credits, and hence profitable, projects would have to be at least fifty units in density, but zoning prohibits fifty units. Without encroaching into the conflict between the political (zoning) and the economics of lending, housing design goes nowhere.

Russell: Architecture is not going to move beyond the nuances that only architects can see until we branch out into other areas. Funny thing is, when you ask a community what they want, it’s usually more parking and no more density. Architects agree that density is good for cities and that the suburbs are unsustainable, yet the public has no idea about this discussion. There are three parking spaces for every car in the U.S.: 720 square feet, counting half the aisle. How big is an affordable unit? 720 square feet. As a culture, we are building parking lots instead of affordable housing.

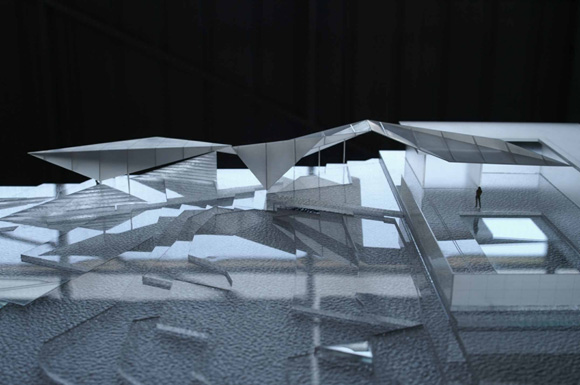

Thom Faulders, Thom Faulders Architecture, San Francisco: The city—contemporary and future—is a construct born of collective behaviors, complex economies, politics, power, flows and expenditures of energies, and so on. What happens when global sameness pervades this arena? One aspect of our work is to develop a language for producing spaces with provisional and idiosyncratic qualities. Our goal is toward the formless rather than the form, so we look to new paradigms generated by the co-opting of technologies coming out of Silicon Valley. What if architecture could be transformed as readily as one “transforms” content and navigation in personal electronics? Would this be a new form of collective empowerment of end users? Probably. Or a noisy mess? Probably. Who knows? But it gets us into the studio each day.

Cruz: I am not suggesting that each of us should turn into the Che Guevara of urbanism, nor that practice as a rigorous, self-referential, autonomous process is worth nothing in a world polarized by social and economic inequalities. We need “good” design. What turns me off is that a hyper project of beautification, whether New Urbanist or avant-garde, continues to hide the true problems of our cities. Practice should accommodate not only building buildings but also building a position. We are so obsessed with the conditions of design that we are not designing the conditions that can yield alternative architectures and, in turn, new cultural experiences.

Craig Scott, Iwamoto Scott Architecture, San Francisco: Most architects focusing on research are ultimately also aiming at the marketplace. If a political stance can break through the common socio-cultural barriers that challenge small experimental practices in the U.S.—the bottom- line mentality of much public and private work, the expectation of an established track record, and the strongly tradition-based construction industry—then more power to political action.

Gail Borden, AIA, Borden Partnership, Los Angeles: My interest in academia stems from the desire to have an impact on the broader profession, to teach towards our collective responsibility. The conversation in architecture needs to return to space. Technology of fabrication, of formal generation, of materials: all of these are interesting, but if they do not aggregate into architecture, which ultimately is about space, something is lost.

Russell: I began teaching in the Masters in Real Estate Development program at Woodbury. Before you take on these tools, you have to be grounded in ethics. An architect or architectdeveloper without a soul is a tool for someone else to use. Technology is not the answer, because it was never the problem. Wiscombe: The market for extreme forms is small, yet such forms are as critical for transforming architectural thought as discovery is for catalyzing scientific revolutions. Moralizing political tendencies in design are too open-ended; architecture can too easily become the tool of factions on both sides. A degree of autonomy is necessary, and the control of space and form is extremely political.

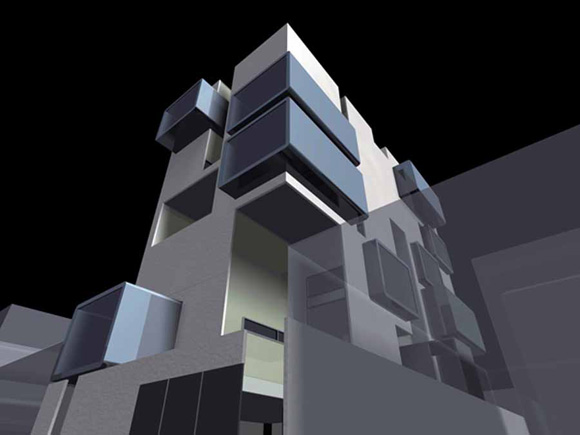

Marcelo Spina, LA PATTERNS, INC., Los Angeles: Architecture engenders spatial conditions that induce new forms of experience and sensation. We aspire to an architecture that best incarnates these conditions, what Peter Eisenman called “presentness,” an aura that persists over time, independent of use or meaning. We want to produce singular spaces that challenge the body and assumed notions of inhabitation. Our interest is not necessarily in producing newness, but rather in articulating moments of local innovation within existing models, like the paintings of Francis Bacon, inserting indeterminacy into matter, variability into figure.

Cruz: French art critic Nicolas Bourriad says form is a tool to anticipate social encounter. I agree, and would like to denounce autonomy, to transcend the property line and my solitude, so that things become messy and complex. That is the ultimate definition of density: to embrace the contradictory. It’s precisely what we have erased from our systems of thought: complexity, not of forms but of social relations. It is amazing how our notions of democracy, as Michael Sorkin reminds us, are based on the right to be let alone. Democracy should be measured by our capacity and willingness to be together in a space: propinquity—like this precarious chat room. Can architecture frame democracy?

Day: My last thoughts have to do with a series of overlapping sensibilities: the minimal and post-minimal, the millennial and post-millennial. Minimalism was about presence, postminimalism about diversified approaches to the same; the millennial about immersion, the post-millennial its ramifications and diversification. We are still at the cusp of the millennial / post-millennial, a moment that will be dated to 9/11 and the mess we’ve made since. Already, the most groundbreaking work of the last few years has the look and logic of amalgamation, collaboration, and informality, rather than the heroic and aesthetically doctrinaire essays of the ‘90s—Super Modernity, Bilbao/ Getty, and FORM.

Peralta: Thanks to everybody for making this forum full of passion. I sometimes feel that students don’t have passion; it’s hard to get them to be critical of our profession. I hope this dialogue demonstrates that to be a young practice requires sacrifice, passion, and dedication.

Peter Zellner is the founding principal of ZELLNERPLUS, an emerging architectural design, planning, and research firm in Los Angeles. He is the author of Hybrid Space—New Forms in Digital Architecture and Pacific Edge—Contemporary Architecture on the Pacific Rim. He teaches in the Design and Cultural Studies programs at SCI-Arc and is a Visiting Assistant Professor at the USC School of Architecture.

Originally published 1st quarter 2008, in arcCA 08.1, “‘90s Generation.”