Here’s why. Architects have mystique. It comes from their magnificent history, creating some of humanity’s greatest achievements and best moments—moments of strength, protection, mystery, excitement, spirituality, earthiness . . . beauty.

Perhaps also it comes from some uncanny sense that architects are members of the world’s most powerful profession. What? Most architects would laugh at that explanation, dismiss it completely. But that’s what mystique is . . . believing something about someone that he or she is sure isn’t true. In the case of architecture, however, it is true. Architects are the most powerful, even if they don’t know it. And that power is about to grow exponentially.

Architects create form, and form creates situations, and situations, as any behavioral scientist will tell you, are the most powerful determinants of behavior, more powerful than personality, history, character, habit, even more powerful than genetics. Architects create beauty, experiences, relationships, communities— and these are what make our lives what they are. Architects do this even when they don’t know they are doing it. That’s why so many designs are awful.

Architecture is about to undergo a transformation that will greatly increase its power. In the words of the American Institute of Architects as it describes its goals for the future of architecture, it will “change the role of architects in the world,” “use design to help resolve the critical issues that face society,” “deal with the most pressing issues of our time,” “serve all of the people.”

I applaud those goals, and agree that they describe what is beginning to happen and must happen in full strength if our democratic society is to survive. If the AIA keeps its eye on that ball, it could very well become a force to transform everything. But what has to happen to the policies and practices of the AIA to fully serve that calling?

First, it must go through a self-examination to see which current practices facilitate that goal and which do not. In my most enjoyable and rewarding days as a public director (non-architect) on the AIA Board of Directors, I nevertheless came to see a number of programs and policies that I would regard as potential deterrents to reaching these new goals. I won’t try to describe them here, but a careful self-analysis by a committee of the board could reveal several. The difficulty in identifying them can be reduced a bit by knowing that they were all instituted to increase the standing and power of architects. But paradoxically, they don’t work that way. Often, just the opposite.

Second, it has to make a distinction as to whether architecture is a business or a profession. Not that it can’t be both, but they are not the same. Business serves “wants,” professions serve “needs.” If architects intend to serve great public interests, they must be able to exercise professional judgment. They cannot commoditize themselves, serve only market interests, or become subordinate to their clients. The AIA could be immensely helpful in supporting such a professional posture, even when architects are serving business. Lawyers, physicians, professors, accountants all serve businesses, but as professionals. Indeed, it is their professional judgment that business needs most.

Third, the AIA must facilitate collaboration, not competition, among the other design disciplines, and among social scientists, technologists, systems analysts, paraprofessionals, volunteers, and many others. To address the great public concerns, architects will need all the help they can get. There will never be enough architects to answer these higher callings. Rather than using its lobbying power to prevent interior designers from becoming licensed—or when I first was on the AIA board, to eliminate inheritance taxes (does that improve architecture?)—it should lobby to help mobilize the diverse resources necessary to reinvent our social and physical infrastructure. Protectionism is no longer an appropriate activity for architecture, if, indeed, it ever was one.

Fourth, architects must return to the leadership role they once enjoyed. To accomplish these great humanitarian goals will require the ability to exert influence at the highest levels. That status is not out of reach. Architects used to be members of high councils of decision making, founded the Union League Club, fought slavery, associated with presidents. Their professional choices must position them in those more influential situations. That is where they belong, sharing their wisdom and perspectives. When it comes to serving the public good, architects can see things others cannot.

Fifth, architects will have to continually redefine what an architect is and does. As they move from the design of bricks and mortar to embrace the design of social systems, to designs that strengthen democracy, liberate the oppressed, improve the quality of life, they will realize that anyone who is still doing only what he or she was trained to do is obsolete.

Sixth, and perhaps the most difficult to accept, is that they will have to devote more of their time, perhaps most of it, to working in the public sector, redesigning the physical and social infrastructures of our society, none of which are working well enough to justify their current existence. Most do not work at all, and some actually make matters worse. Education, transportation, healthcare, prisons, communities, and media are all failing. On almost every index comparing nations in terms of their accomplishments, which our nation once dominated, we seldom rank even in the top ten, and are often at or near the bottom. We cannot continue this downward spiral.

This is a tough order for the AIA. For decades it has worked hard to orient its members to serve the private sector, business, the market, presumably because that’s where the money is. But not only is there eventually big money in serving the public sector, it is close to impossible to expect business to take a central interest in those socially responsible goals. Businesses, as we should have learned over this last century, cannot prioritize socially responsible behavior. They must follow the market, and the market, as Princeton economist and political scientist Charles Lindblom notes, is brutal and mindless. Creating big box stores that destroy community is far from the only architectural activity that confirms that statement. Economist Milton Friedman got it right when he said, “The only social responsibility of business is to make a profit.” Keeping our economy strong by following the market is indeed a vital responsibility, because there never has been a democracy without a market system. But it isn’t the road architects must take to reinvent our infrastructure.

These humanitarian goals needn’t be approached as charity work. Other professions, like education, healthcare, and criminal justice—professions we think we cannot do without—are supported largely by the public. They receive hundreds of billions every year from the taxpayers. Their planning is in the trillions. That should be, can be, must be the future of architecture. The AIA could facilitate that vision. Spending on architecture, unlike spending on wars, can be an investment. We get it all back, and more.

The current government expenditure, the 700 billion dollar “Stimulus Package,” is largely intended to rebuild our infrastructure. Think what the profession of architecture could have done had it been prepared with the vision, organization, and expertise necessary to respond to that opportunity.

The future of our democracy, indeed the future of our nation, is deeply threatened. Our infrastructure, both physical and social, needs to be completely redesigned. Yes, redesigned. Architects have our future in their hands. Will they answer that calling?

Let’s keep reminding them that they still have that secret weapon, that beautiful and reliable mystique.

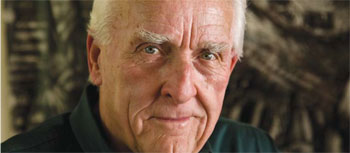

Richard Farson, PhD, psychologist, author, and president of the Western Behavioral Sciences Institute, recently published The Power of Design: A Force for Transforming Everything. He served as an AIA Public Director, 2000-2001.

Originally published 1st quarter 2011, in arcCA 11.1, “Valuing the AIA.”