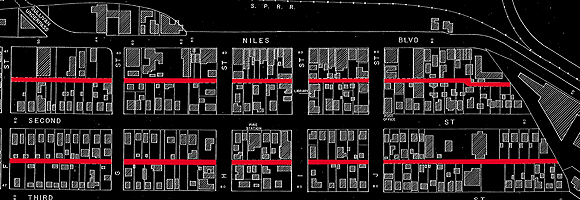

Two alleys run the length of the town of Niles, California, parallel to its three main streets. Their function is to provide useful access to the rear of properties. There were no automobiles in 1888 when the town was laid out, and the dust thrown by horse-drawn wagons was something to avoid. It was best to bring the wagons around the back. The alleys create the urban fabric and make possible the architectural vocabulary of the town’s streets: picket fences, Western façades, and the conspicuous absence of suburban, two-car garages. The “Main Street” nature of Niles Boulevard exists because of the commercial service access the alleys provide.

In 1956, the City of Fremont was incorporated, combining previously unincorporated Niles, Mission San Jose, Centerville, Irvington and Warm Springs. Conflicts between revitalization of the towns and suburban development became immediately apparent. In December of 1956, eleven months after incorporation, Fremont asserted that the public alleys in Niles were not part of the incorporation and that it was not responsible for their distressed condition. It certainly did not intend to maintain them.

To compound the situation, the City declared Niles an historic district but to this day refuses to draft zoning regulations that would support its historic development patterns. To the contrary, in 1997, it rezoned 75% of the houses into a non-conforming situation, requiring a variance for any changes. It does not allow improvements that acknowledge the alleys.

How would things be different if, since 1956, the alleys had been maintained and utilized? How many businesses would have thrived on easy deliveries? How many commercial property owners would have expanded their buildings? How many new shoppers and businesses would have been attracted? How many residences would still have picket fences? How many garages would be accessed from the alleys instead of the main streets?

The impact of the alleys on the townscape of Niles is profound. In a healthy state, they would provide systemic vitality to the local economy and an experiential framework for understanding the past and imagining the future culture of Niles.

Author Paul Welschmeyer, AIA, is an East Bay native whose professional experience began with Ratcliff Architects in Berkeley and continued with Studios Architecture in San Francisco. His private practice began in 1991. Currently his practice revolves around custom residential and commercial interiors, both of which include a focus on adaptive reuse, historic conservation, and sustainability. He is a Niles resident and was a member of Fremont’s Historic Architectural Review Board (HARB) from 1991 to 1998. He thanks the staff of the U.C. Berkeley Environmental Design Archives and Richard C. Peters, Professor of Architecture Emeritus, U.C. Berkeley.

Originally published 4th quarter 2008, in arcCA 08.4, “Interiors + Architecture.”