One of the ironies of modern urban life is that municipalities spend millions of dollars each year to contain and dispose of stormwater, millions more to acquire the fresh water they need. The irony is especially pronounced in the American West, where scant rainfall can be nonetheless destructive and population centers are often far removed from adequate water supplies. Though the average viewer might require interpretive signage to understand them, some of the results are observable from any of the landmark bridges spanning the Los Angeles River. Most of the year, a trickle of water flows down the narrow center groove of the river’s concrete box. But during the rainy season, the box sometimes fills almost to overflowing with a juggernaut of water, lethal to anyone foolish or unfortunate enough to enter it.

The river can be deceptive as well as dangerous. Most of that dry-season trickle is effluent from L.A.’s sewage treatment plants. Accordingly, very little of it originates in the watershed of the river that’s carrying it. Instead, it has traveled hundreds of miles from one of the three places that provide 70 to 85 percent of Los Angeles’ fresh water: the Central Valley, the eastern Sierra, and the Colorado River. Only 15 to 30 percent comes from local aquifers.

The concrete box, often referred to as the river’s tomb, came about as a direct result of floods that regularly devastated the basin, notably in 1914, 1934, and 1938. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the County Flood Control District were charged with one of the largest public works projects ever undertaken: to contain the runoff from the 100-year storm and free the low-lying environs of the river from the threat of flooding.

The project was completed in the late ‘60s. Within twenty years, there was reason to suspect that the system of retention basins, channels, and levees might, in some places, be capable of containing only a 25- or a 40-year storm. The designers had simply been unable to imagine the rapid urbanization of the watershed and the proliferation of hardscape that took place after the war. In particular, they had thought that the upper watershed, the San Fernando Valley, would remain largely agricultural. The reality is that about two thirds of the surface of the City of Los Angeles, including the Valley, has now been covered with impervious materials. Less exposed soil is available to absorb stormwater, which therefore runs through the streets and into the flood control channels. The lost opportunity for groundwater recharge is also an issue of major concern in an increasingly tight water market.

The persisting threat to property values and human life could not be ignored. In the mid-‘90s, the Corps of Engineers and the county Department of Public Works (heir to the Flood Control District) proposed the LACDA (Los Angeles County Drainage Area) Project, which would answer the threat by topping the levees along the river’s lower twelve miles with concrete parapets. The ultimate futility of fighting the effects of concrete with more concrete provoked debate about the underlying watershed management issues, and, in May 1995, three environ- mental groups sued to stop the project.

The suit, filed by Friends of the L.A. River, Heal the Bay, and TreePeople, was unsuccessful; the LACDA project is scheduled for completion late this year, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency is gradually eliminating building restrictions and flood insurance requirements over large areas of the floodplain. But one condition of the settlement was that the County Department of Public Works investigate alternatives, such as the ones advocated by the petitioners in the suit, to traditional stormwater management. An active and increasingly influential Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers Watershed Council, in which Public Works is an important participant, was one outgrowth of the controversy.

Another was TreePeople’s T.R.E.E.S. Project. The organization had been a reluctant petitioner in the LACDA suit; its strength was working with public agencies to inspire communities and individuals to take responsibility for the quality of their environment. Tree planting was, and is, the focus for that inspiration. But where TreePeople views trees as watershed management infrastructure, agencies and the general public tend to see them simply as decoration. The T.R.E.E.S. (Transagency Resources for Environmental and Economic Sustainability) Project promotes strategic tree planting and a range of other watershed best management practices (BMPs) as sustainable alternatives to river channelization and other practices that treat only symptoms and do nothing to replenish scarce resources. The LACDA controversy had also made it clear that infrastructure agencies were working independently on related problems in the watershed, with little communication or sharing of resources. There are substantial economic, environmental, and social benefits to be derived from a cooperative approach to designing and maintaining our urban landscape. The purpose of the T.R.E.E.S. Project is to demonstrate the feasibility of such an approach and to facilitate the cooperation.

The first step was to point the way toward redesigning urban sites to function as watersheds. A 1997 charrette brought together for that purpose some of the nation’s foremost landscape and building architects, engineers, hydrologists, urban foresters, government officials, and community leaders. They worked intensively for three days on plans for five representative urban sites — a single-family home, a multi-family dwelling, a high school, a commercial site, and an industrial site — with an eye to addressing the area’s environmental concerns. Among those concerns, each typically addressed by a separate authority, are wasteful use of potable water, stop gap flood control policies, water pollution from storm runoff, costly water importation and the desertification of exporting areas, high rates of energy consumption for cooling, large amounts of green waste using up landfill space, urban blight and its destabilizing consequences, and youth unemployment.

The tangible outcome of the charrette process was a collection of designs for retrofitting individual properties to function as watersheds. Each site design addressed several of the environmental issues in question, each with a specific mix of BMPs. The results were published in 1999 under the title Second Nature: Adapting L.A.’s Landscape for Sustainable Living. But the participants also came away with a new inspiration: we can indeed achieve sustainability, beautify our environment, and employ citizens as its caretakers. And we can do so at less than the cost of current piecemeal strategies that fight, rather than work with, nature’s cycles.

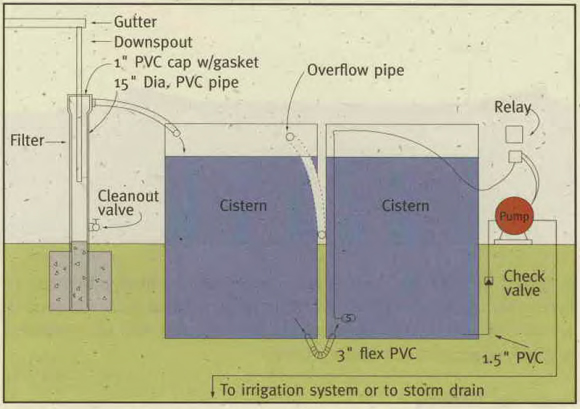

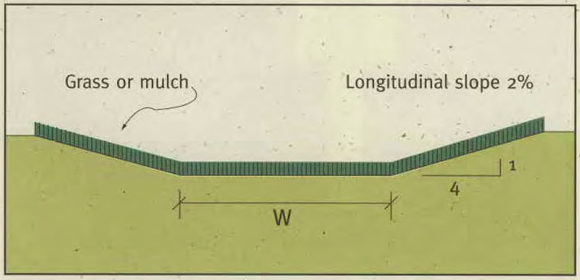

The Hall House, a private single-family residence in South Central Los Angeles, was the first of the five sites to be built. It has been retrofitted to capture and retain onsite the runoff from a 100-year storm event and to reuse all the site’s green waste. Some of the water is stored for irrigation; the rest is available for direct groundwater recharge. The yard waste is recycled as mulch, eliminating the need for transport to and space in a landfill (green waste accounts for 30% of the household waste stream). The watershed BMPs employed at the site include a roofwater washing unit that diverts the contaminated “first flush”; a partially buried 3600-gallon fence-line cistern; a vegetated and mulched swale; retention grading in the front and back yards; and a dry well that filters runoff from the driveway before returning it to the groundwater.

TreePeople and the USDA Forest Service are conducting a two-year study to record weather information and monitor the performance of the BMPs at the home. A weather station, flow meters, and a data logger have been installed at the demonstration site, and an adjacent property is the control site. The push for sustainable watershed management having moved from the naysaying to the investigative stage, the data gathered here will help determine which BMPs suit which conditions, how well they work, and how they might be improved.

Influenced in part by the Second Nature charrette and the demonstration at the Hall House, the L.A. County Department of Public Works recently tabled plans for a $42 million storm drain, intended to solve a chronic flooding problem in a San Fernando Valley sub-watershed. Instead, it has lent its support to retrofitting the entire 2700-acre Sun Valley watershed in accordance with T.R.E.E.S. principles. This turnabout presents an ideal opportunity to show that new watershed management protocols can control flooding by addressing causes instead of effects. At the same time, they offer multiple benefits to draw participation and funding from a range of agencies: improved water quality (by reducing polluted runoff), augmented water supplies (through increased groundwater recharge), greening of the community (with tree planting and retention/detention basins that double as parks), creation of jobs in retrofit construction and BMP maintenance, and improvements to the general quality of urban life.

Agencies, elected officials, civic groups, non-profit organizations, and businesses convened as the Sun Valley Watershed Stakeholders Group late in 1998. Its stated mission was “to determine the feasibility of solving the local flooding problem while retaining all stormwater runoff from the watershed; increasing water conservation, recreational opportunities, and wildlife habitat; and reducing stormwater pollution.”

The Group’s overall watershed retrofit plan was first presented to the public in August 2000. County Public Works Deputy Director Carl Blum and TreePeople President Andy Lipkis presented a vision of a green and sustainable Sun Valley, where stormwater would be transformed from liability to asset. The stakeholders would pool their resources and retrofit the watershed with retention basin parks, cisterns, strategic tree planting, permeable pavement, and groundwater infiltrators. Other strategies, such as pavement removal in schoolyards and parking lots and the widespread use of mulch, would also be part of the mix. A successful demonstration project at this scale would constitute a milestone in watershed management and could be expected to draw international attention.

Recently, having determined that its general plan was indeed feasible, the Group amended its mission statement to reflect a new resolve: it now intends to solve the flooding problem. Current movement is on two tracks. One emphasizes outreach to the community and education on watershed issues. Its purpose is to develop the public support necessary to ensure the project’s success. The other is the implementation of pilot projects in the watershed. They will lay the groundwork for the retrofit of the entire watershed, which is expected to take 10 to 15 years.

The narrator in John Shannon’s detective novel, The Concrete River, observes, “Few people in L.A. noticed the natural features that were still there beneath the grid of streets — like the slope a mile north of Rose that had been the north bank of the floodplain. He had once enjoyed knowing things like that, the broken geography under the asphalt and the lost flora and fauna.” It’s true we don’t usually notice these natural features until we’re rudely reminded of them, but the folly of ignoring them is becoming increasingly evident. The broken geography may not be completely reparable, the specific flora and fauna restorable, but they provide clues toward a more sustainable city, if we’re willing to follow them.

Author David O’Donnell is T.R.E.E.S. Project Associate at TreePeople, where he writes grant requests, produces newsletters and educational materials, and puzzles over the arcana of California water issues. He is none the worse for his recent physical contact with the Los Angeles River, from which he collected water samples as part of the effort to establish legally permissible levels of various pollutants.

Originally published 4th quarter 2001, in arcCA 01.4, “H2O CA.”