In writing about design as a catalyst for social change, it is necessary to begin with two qualifying remarks. The first is that I will be writing about design at the level of settlements, not buildings: the focus will be on urban design. The second is that I will be illustrating the argument with material from South Africa. There clearly are significant contextual differences between South Africa and the USA (the most notable of which is the extent of poverty). I sense, however, that there are also some similarities. Three of these are particularly important.

First, with increasing globalization, patterns of poverty and inequality are redistributing: increasingly, no country will be immune from the challenges these pose. Second, the use of limited natural, fiscal, and other resources is increasingly a global issue, and the need to use resources wisely will rise in importance on all national agendas. Third, the philosophic basis underpinning the recent spatial development of cities in many parts of the world is remarkably similar: most have been significantly informed by the precepts of modernism.

This article is structured into four parts. In the first I pose the question, “How well have we been doing in the art of settlement-making?” and, through it, identify some structural problems. In the second, I suggest a number of changes that are essential for substantial improvement in urban performance. In the third, I focus on a sequence of projects drawn from Cape Town to illustrate the meaning of the words. Finally, I draw some generalized conclusions about the implications of these issues for all of us as spatial designers.

The Problem

How well have we been doing in the art of settlement-making over the last seven decades, the period when society consciously broke with centuries of tradition to pursue a brave new urban future? The short answer is, not well at all. Despite the enormous amounts being invested in urban areas internationally, emerging urban environments are commonly monofunctional, sterile, monotonous, and inconvenient places in which to live. In particular:

- Their sprawling low density forms result in massive destruction of valuable agricultural land and land of high amenity;

- They generate huge amounts of vehicular movement with associated and worrying increases in congestion, in air and water pollution, and in energy depletion;

- They mitigate, through their fragmentation, against the achievement of efficient and viable public transportation systems;

- They result in environments that are highly inconvenient and expensive places in which to live and that, frequently, increase poverty and inequality, since it is the poor who are most affected. They are impositionary environments, since they reduce people’s choices about how their time and money should be spent;

- They generate limited opportunities for small business generation, largely because of diffuse and diluted thresholds. At the same time, increasing numbers of people globally will have no option but to generate their own livelihoods;

- The quality of the spatial environment is ubiquitously poor, if not directly hostile. These environments degrade people’s dignity; and

- They result in environments that are increasingly difficult and expensive to maintain.

The root causes of these problems are not professional incompetence or a lack of political will (although both of these are evident around the world). The causes are structural: they result from the very nature of the modernization paradigm. There are three primary connections between modernism and poor urban performance:

- The first is the profoundly anti-urban or suburban ethos underpinning the paradigm. The freestanding pavilion surrounded by private space is promoted as the dominant image of the ‘good urban life.’ The same model is promoted, even as the plot size is cut to a point where the system yields the benefits neither of urbanity nor of green space. It is becoming increasingly apparent that, in most countries of the world, this model and the sprawl which inevitably accompanies it are non-sustainable.

- The second is that the model is based on separation and mono-functionality—yet sterility is the inevitable consequence of mono-functionality, regardless of how skillfully environments are made.

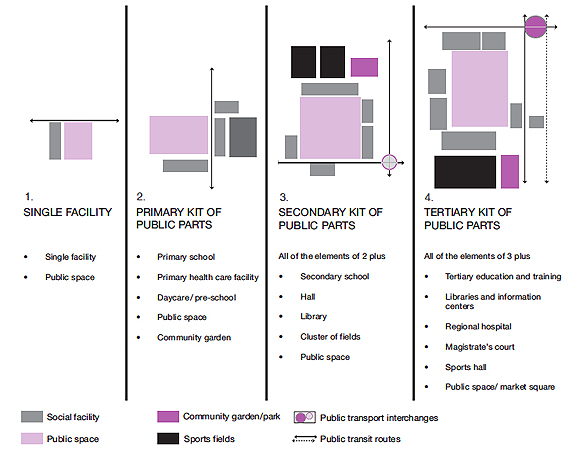

- The third is that modernism has been underpinned by programmatic approaches to settlement making. The focus of programmatic approaches is land use. Idealized land use patterns are conceptualized, neatly separated, and distributed in space. The approach is essentially quantitative. Space demands are ‘scientifically’ calculated on the basis of thresholds, and a land use schedule is generated (x number of households can support y primary schools, z secondary schools, a clinic, so many meters of commercial space, and so on). Planning and design then become the more or less rational distribution of the parts or elements. In this conception, settlement making is seen as a rational, comprehensive, highly controlled process leading to balanced end-states.

The problem with these approaches is that the environments which result from them are inevitably sterile, for two main reasons. First, the ‘science’ of prediction upon which these approaches are predicated is notoriously unreliable. The result is environments that appear permanently incomplete, with large amounts of residual space lying around waiting for events to ‘catch-up.’ This, in turn, dilutes thresholds and frequently ensures that events never do catch up.

Second, plan-making is essentially driven from the bottom-up: from the parts. When this approach is applied to housing—particularly low-income housing, which is the major growth component of towns and cities internationally—it is played out like this: shelter is viewed as the highest priority, and the individual dwelling unit—usually the freestanding, single story unit—is seen as the basic building block of urban environments. The first task therefore is seen as the need to service the site (with water, sewage disposal, road access, and—sometimes—electricity) and, in relation to this task, concerns of engineering efficiency, as opposed to any social or environmental concerns, dominate. Collections of individual units are then arranged into discrete clusters or cells (neighborhood units and the like), in the naive belief that this promotes community, and they are usually scaled by the requirements of machines, particularly the motor car (even though the majority of people do not own cars and will not do so within the foreseeable future). These collections then give rise to a notional program of standardized public facilities, seen as independent, self-contained entities. Space for them is distributed evenly within the cells to optimize ‘access’ and ‘equity.’ In short, settlements are built from the bottom up.

The reality of all developing countries, including South Africa, however, is that financial resources are woefully limited. In this climate, a number of consequences inevitably results from the approach described. First, levels of housing assistance, even to those who gain access to such assistance, are continually cut back (plots get smaller and levels of shelter and utility services are reduced), but always within the same model, centered on the concept of the freestanding unit. Second, a continually smaller proportion of households gains public housing assistance. ‘Islands of privilege’ are created, and these in turn give rise to waves of negative social practices (downward raiding, war lording, bureaucratic corruption, political patronage, and so on).

Third, cuts occur in social services: on the one hand, not all the planned social infrastructure (schools, health facilities, and so on) can be provided; on the other, those facilities that are provided are cut to a point where their operation is severely impaired—for example, in the case of schools, libraries are minimally stocked, science laboratories are poorly equipped, sports fields are not maintained, and so on. The ‘equitable,’ ‘accessible’ pattern becomes inequitable and inaccessible, since the facilities that exist are embedded: they are located to serve specified local communities exclusively, and many households can therefore gain access to essential social services only with great difficulty and at considerable expense, if at all. Since there is no way that individual households can substitute for these essential public services, the degree of disadvantage is enormous. Further, the (usually excessive) spaces allocated for facilities that do not materialize fragment the urban fabric and frequently become dangerous, environmentally negative, liabilities. Spatially, the inevitable consequence is sterility, since nothing holds the whole together.

A Way Forward: Creating a New Tradition

Two fundamental paradigm changes are essential if significant improvements are to be achieved. The first is enthusiastically embracing an urban, as opposed to a suburban, model of development. Particularly, settlements need to be scaled to the pedestrian and to efficient public transportation. This means the reversal of some of the central tenets of modernization:

- Compaction, as opposed to sprawl

- Integration and mix, not fragmentation and separation;

- Equity, as opposed to increasing inequality;

- Sustainability, as opposed to inefficiency and waste; and

- Concentrating on collective actions—actions that impact positively on the lives of large numbers of people, as opposed to the individual household—as the basic focus of social change.

The second is shifting from programmatic to non-programmatic approaches to planning and design.

Non-Programmatic Approaches

Non-programmatic approaches are different in a number of important respects from programmatic ones, and this way of thinking is central to urban design. First, they are driven by a concern with the performance of the whole, not the maximization of the part. They are based on the central realization that, for the whole to work well, no part can be maximized, for compromises are required.

Second, their focus is not on land use but the accommodation and celebration of human activity in space.

Third, the emphasis is not on idealized forms but on thinking from first principles, based on the two ethical legs of environmentalism and humanism. This thinking starts not with assumptions about technology, but with the lowest common denominator: people on foot.

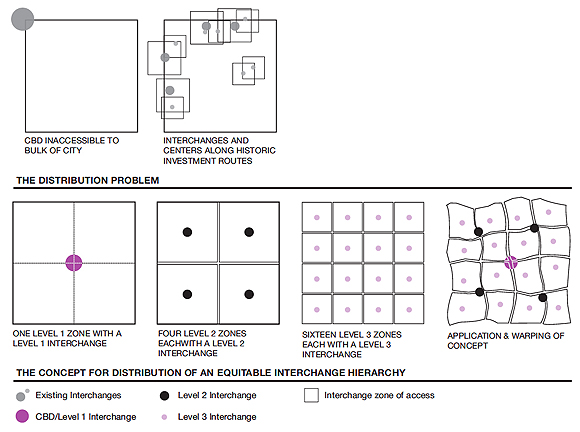

Fourth, they do not seek to determine spatial distributions of activities directly through autocratic, top-down directives but through manipulating the logic of access, to which all activities respond, in order to generate broadly predictable outcomes.

Finally, they do not attempt to define the good urban life, applicable to all people, but concentrate on the creation of choice. In this sense they are enabling, not prescriptive.

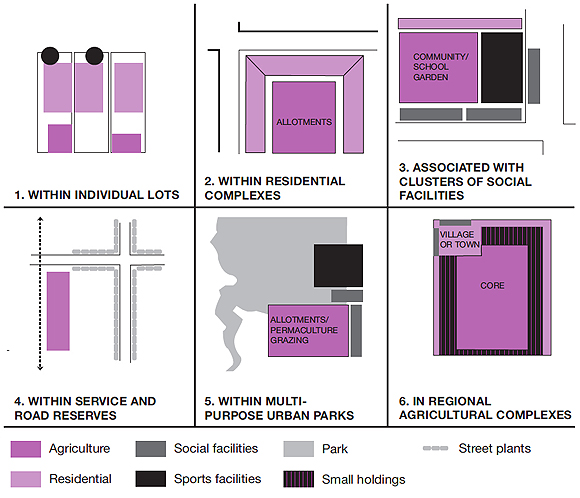

Structure

The concepts of structure and space are central to non-programmatic approaches. It is therefore necessary to define them in greater detail. Structure is the design device traditionally used in settlement making to order the landscape. The main elements of public structure (generically: space, place, movement, institutions, and services; more commonly and more specifically, these translate into green space, all modes of movement including walking, public urban space, social facilities, utility and emergency services) are manipulated and coordinated to create a geometry of point, line, and grid. The geometry generated by the association among these elements creates a logic to which all activities, large and small, formal and informal, public and private, respond in their own interests.

The key to understanding the spatial logic of structure lies in the concept of access. In effect, the geometry created through the co-ordination of the public elements of structure generates an ‘accessibility surface’ across landscapes: it creates a reference system of points and lines of greater or lesser accessibility. Further, the system is a hierarchical or differentiated one: it creates different levels of access to different types of opportunities (greater or lesser access to green space, for example, is defined by the relationship of land parcels to the pattern of green space).

Every activity has its own logical requirements in terms of access. At the most fundamental level, these logical requirements relate to variations in the needs for publicness (exposure) or privacy (secretiveness). All activities have these requirements and seek to optimize them. The more complex the accessibility surface, the greater range of choices offered to decision-makers. Conversely, the more simplified the structure, the greater the tendency for highly accessible locations to be appropriated by the strongest players requiring exposure, to the exclusion of all others.

The structural system therefore establishes a logic of exposure and privacy to which any activity can respond. It is through this structural system that rich choices are offered without imposing a particular form of lifestyle for everyone. The system is not dependent on judgments about what constitutes the ‘good’ urban life, as is the case in programmatic approaches: it simply creates choices. The richer the range of choices, the better the system. In this way, it allows people to self-actualize. In primarily residential systems, for example, real choice does not relate to architectural style or issues relating to how the dwelling is organized or designed. Rather, it relates to choices in lifestyle, from very private (and frequently somewhat less convenient) living to very public, intense (and more convenient) living. This way of thinking, then, does not deal with ‘either-ors’ (either access to the private green space of suburbia and almost no convenience—to the extent that people are forced to spend many hours a day in cars ferrying children—or public living with no access to green space), as tends to be the case with the current urban model, but with degrees of choice, within limits.

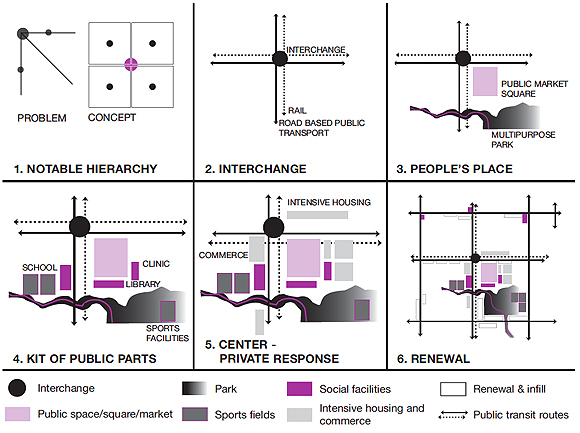

Space

In the same way that it is possible to create a hierarchy of access, it is possible to create an associated hierarchy of public space. In non-programmatic approaches, all public space is seen as social space (it is not residual space). All public space is multi-functional space. These are the places where children play, old people meet and gossip, lovers court. When these spaces are properly made (when they are defined, enclosed, humanly-scaled, surveilled, and landscaped) they massively enhance the enjoyment of the activities they accommodate, and they determine the dignity of the entire environment. The primary role of buildings in this regard is to make and to define the public space.

Conversely, when the public spaces are hostile, the entire environment is hostile, regardless of how much is invested in individual buildings. This was one of the great failures of modernism: the movement elevated the freestanding object (the building) as the focus of design attention over all else and, in the process, fragmented much of the public environment.

Design is the creative integration of these different forms of hierarchy (the hierarchy of access and the hierarchy of space) into a framework (not comprehensive end-states) which creates a logic of publicness and privateness within which all activities, large and small, can find a place in terms of their own requirements for accessibility. At the same time, the spatial quality of the framework contributes directly to the quality of the environment and life. In this integrating process, the ordering concept (the idea) is sympathetically molded to, and informed by, the landscape. This molding warps and distorts the idea, thereby giving it richness and life, but it may not destroy it.

The Dignified Public Places Program of the City of Cape Town

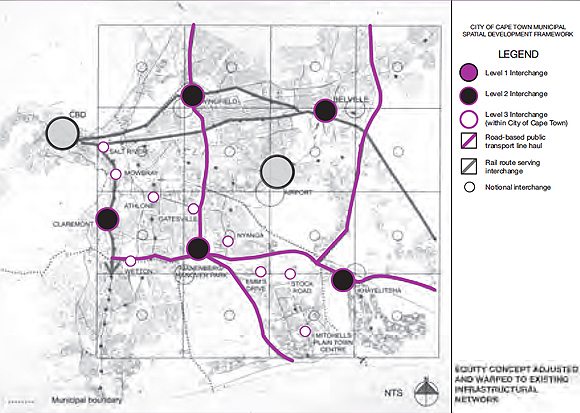

In 1999, I was appointed core consultant to head up a small team to develop a Spatial Framework for the City of Cape Town. The Framework attempted to set out a logical argument for managing the emerging spatial structure of the city in a manner that, progressively and cumulatively, achieves greater human dignity, equity, integration, and sustainability and a sense of place over time, in the face of severe fiscal constraints.

The creation of high quality public space was seen as central to achieving the aims of the framework. The argument recognized that, while the quality of the public spatial environment is important for everyone, it is crucial in the lives of the poor. A defining characteristic of poverty is that poor people spend a large amount of time in public space, because the individual dwelling unit cannot accommodate all, or even most, of a household’s daily activities. Accordingly, urban public spaces (streets, squares, promenades, and green spaces) should be seen as representing the primary form of social infrastructure in cities. When these spaces are properly made, they promote human dignity: everyone is the same within them. It is this point, I believe, that defines the strongest connection between environment and behavior. When environments have no dignity, they generate a lack of self-esteem, and they limit a sense of possibilities. They also represent the lowest entry-cost form of economic infrastructure, particularly for informal trading.

It was also recognized that it is impossible to direct the same amount of public investment to all places. An important program which resulted from the process of plan formulation early on, therefore, was the ‘people’s places program,’ later termed the ‘dignified public places program.’ Highly accessible and structurally significant places were identified through the logic of the plan and were singled out for public investment, to create special places that would become community foci in the lowest income areas and, hopefully, over time, attract private investment to them. The idea, then, was one of strategic urban surgery to encourage spontaneous regeneration.

The primary purposes of this program are four-fold:

- To create places of dignity for informal gathering in the poorest parts of the city;

- To act as a catalyst to encourage private investment;

- To create opportunities for small business—most of these spaces also operate as markets; and

- To create more hygienic conditions for the selling of foods, particularly cooked food.

Sixteen of these projects have been completed. The intention is to steadily roll out from this beginning at a rate of ten to fifteen projects a year.

Significantly, the budgets for all of these projects have all been negotiated. They are all made up of voluntary contributions from a number of different line function departmental budgets (particularly design services, transportation, economic development, and parks and bathing). This is the first time this has ever occurred in the history of Cape Town. The process has not been easy: there are still dimensions of conflict around different departmental agendas and issues of management. Nevertheless, the projects have had a profound impact in terms of promoting interdisciplinary thinking, and there are rapidly growing levels of co-operation and trust. In the longer term, there is a real chance that these interdisciplinary projects will have significant impacts on institutional design. (Incidentally, the program was awarded the Ruth and Ralph Erskine Prize for Architecture for 2003.)

Conclusion

Any objective review of current settlement-making practices internationally must conclude that the professions concerned with the built environment are not serving their societies particularly well. Bringing about substantial improvements will not be easy, but it is essential. In my view, it is the primary responsibility of the design professions to initiate these changes. Change will not come from elsewhere.

What are some of the implications for this way of thinking for us all, as spatial designers?

First, we need to rediscover a belief in the importance of the role of spatial design as an instrument of social change in society. Our primary role in society is monitoring spatial trends and placing before society a new and better sense of possibilities, however radical or unpopular this may be perceived to be. This is our expertise; its measure is not in terms of the rich and powerful few, but in the impacts on the common men, women, and children without access to large personal resources or to sophisticated technologies. We need to proudly embrace our fundamental social role as promoters of social justice.

Second, we need to return to a position that locates the beginnings of all design on the two ethical legs of environmentalism (the needs of nature and the need to design sympathetically with these) and humanism (the needs of people), as opposed to pre-occupations with technologies and form.

Third, we need to recognize that any design problem is only part of a broader whole. The primary responsibility of any project is to improve the quality of the whole. It is a great design decision, for example, to recognize that sometimes buildings are more appropriately background objects, whose role is to integrate, as opposed to putting all design on an aggressive, competitive basis with all other buildings.

Fourth, we must recognize that spatial quality is defined by the quality of the public spatial environment, not the individual object. The primary responsibility of all buildings and spatial objects is to contribute to the quality of the public spatial environment.

Finally, we must recognize that the distinction between ‘public’ and ‘private’ projects is an erroneous, misleading one. Every project offers an opportunity (however great or small) to give something back to the public at large, and it is the responsibility of every designer to seize that opportunity. Good design begins with recognizing the public good associated with a project.

If we begin to do these things, consistently and honestly, on a daily basis, we will begin to regain the respect of the public at large and the absolute need for good spatial design will be increasingly recognized. If we do not, our role will become increasingly marginalized.

Author David Dewar holds a BP chair in City and Regional Planning in the School of Architecture, Planning, and Geomatics and is deputy-head of the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment at the University of Cape Town. An outspoken critic of apartheid policies, he was co-founder and director of the Urban Problems Research Unit. He is author or co-author of nine books and over 220 articles and monographs on urban and regional development. He consults widely in Southern Africa and Mauritius on issues relating to urban and regional planning and development. From 1999 to 2001, he was a member of the National Development and Planning Commission (the first planning-related commission in South Africa for over 60 years), charged with drafting a Green Paper on the Planning System in South Africa. In 2000-2001, he was core consultant for a Spatial Development Framework for the City of Cape Town. He has received numerous professional awards in planning and architecture. This article is a version of papers previously presented to the AIA Sacramento Chapter and at the Monterey Design Conference, with the support of the Leonakis Beaumont Group.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2004 in arcCA 04.2, “Small Towns.”