arcCA asked each professional architecture school in the state to identify and describe a program or initiative that aptly characterizes the philosophy, attitude, direction, or emphasis of the school. Our goal was to avoid generalities, instead presenting concrete instances that will suggest meaningful differences among the institutions. Nine of the ten schools responded. These are their responses, in order of the age of the architecture program—founding dates indicated in parentheses—eldest first.

UC Berkeley (1903): The Cal Design Lab @ Wurster

Jennifer Wolch, Dean

Over the past decade, something called “design thinking” has swept business, engineering, and other professions the world over. Now, at Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design (CED), faculty and students are coming together with others from across campus—entrepreneurs, information technologists, industrial designers, and engineers—to work on critical design challenges.

The medium is the studio environment—nothing new for architects, planners, or landscape architects, but decidedly different from the traditional environments of other professionals. The experiment has been crafted to understand whether disciplinary cross-talk, exposure to a wide variety of design methods and ways of thinking and doing, and collaborative work around prototypes and projects can lead to a new form of educational experience and design practice.

The experiment started when I was approached by CED alumnus and lecturer Clark Kellogg, along with Sara Beckman and John Danner from the Haas School of Business. Clark is an architect, designer, and expert on innovation; Sara pioneered UC’s popular course on product design, along with her colleague Alice Agogino from Mechanical Engineering; and John is a management guru and senior fellow leading courses in new venture development and global poverty. They wanted “think-do” space for a collaborative design studio: for classes, informal group projects, and faculty seminars. In the face of their energy, enthusiasm, and vision, I quickly carved out a corner of the 5th floor studio and said: Go for it!

Because enthusiasm is infectious, the deans of the Haas School of Business and the Information School also signed on to participate in the experiment. Dean Rich Lyons of the Haas School of Business recognized that this type of space would afford MBA students a chance to work in a completely different way, not only because it encourages collaborative thought but also because it allows the persistence of visual information over time. After several iterations, we settled on a name: the Cal Design Lab. The 5th floor space is the Cal Design Lab @ Wurster, but we hope that eventually—with community and corporate support—there will be Cal Design Lab facilities in other corners of the campus, creating a network of intersecting groups focused on design in its many instantiations.

In July, a charrette was held to think through how to equip the space for future use. Faculty and staff from CED’s Department of Architecture, Haas School of Business, Information School, and College of Engineering participated, as well as senior staff from Steelcase, keen to nurture an experiment into future learning styles and their physical environments. Even without fancy furnishings, however, students were already being exposed to design thinking in practice; last spring, Jon Pittman, a senior executive from Autodesk, taught his course on the role of design as a competitive strategy there. This year, introductory courses, mini-courses, and project-based courses from architecture, engineering, and business will cycle through the space. Student teams are apt to prototype green products, frame innovative business ventures, craft social marketing campaigns, collaborate around design competitions, and more.

The Cal Design Lab @ Wurster will also be the locus of cross-disciplinary faculty seminars focused on the design process. This effort builds on CED’s tradition of scholarship on design theory and methods; in the 1960s, Professor of Architecture Horst Rittel coined the idea of “wicked problems” and used systems theory and data to understand how designers crafted solutions to them. The seminars’ goal is ambitious: how can we retrieve the still powerful pieces of this scholarly legacy, while recognizing that today’s thinking has changed under the influence of subsequent intellectual currents and a communications revolution that necessarily alter our understanding of how designers think about problems?

Cal Poly San Luis Obispo (1964): Professional Studio

Henri de Hahn, Department Head

Cal Poly is heir to the French polytechnic education, one that finds a balance between theory and practice. This dual identity remains at the core of an architectural education that is committed to nurturing the practice and practices of architecture. In 2005, the department set in place an innovative professional off-campus program that responds to emerging trends in the profession.

A Professional Studio, a collaboration between the Architecture Department and an architectural firm, grew out of conversations with the KTGY Group, Inc. and developed into the quarter long placement of students in firms. During the quarter, the students work as paid co-op employees and are taught a fourth year design studio by firm members.

The program provides students with professional work experience and financial support; a comprehensive design experience informed by the firm’s deep knowledge of a building type, design philosophy, and processes; and an immersive experience in the profession of architecture. Students are involved in co-op work about 24 hours per week and in design studio about 16 hours per week, with evenings and weekends available for additional work on design projects.

The first Professional Studios were offered by KTGY during the 2005-2006 academic year. WATG of Irvine joined for the 2006-2007 academic year, and since then LPA of Irvine, Roesling Nakamura + Terada Architects of San Diego, Zimmer Gunsul Frasca Architects of Los Angeles, and Gensler of Santa Monica have joined the program. Firms typically participate in the program for one or two quarters each year and move in and out of the program as their workload permits. We are fortunate to have the long-term commitment from firms that allows us to offer multiple Professional Studios as an ongoing part of our curriculum.

A Cal Poly faculty member works with the identified firm members to develop the design problem and mentors them in course organization and teaching. The faculty member visits the firm for a mid-term evaluation of student progress and to provide support for the firm members regarding teaching issues. At the end of the quarter, the faculty member, firm members, and students make a presentation at Cal Poly, which all faculty and students are invited to attend.

All fourth year students in good academic standing are eligible for the program. The faculty member, in consultation with the student and firm, makes student assignments based on interest, GPA, and portfolio. Students work in a range of work assignments appropriate to their capabilities and the firm’s needs. They are involved in such things as site visits, client and consultant meetings, production meetings, and CIDP/IDP meetings. The goal is to make the co-op experience as broad and rich as possible. Students create a report on their co-op experience and provide examples of their work. The program mentors at the firm provide feedback on the student’s co-op performance and a grade recommendation.

The firm-based design studio is not intended to replicate an on-campus studio, but to provide students a comprehensive design experience informed by the firm’s knowledge, philosophy, and processes. It is important that the design project, process, and outcomes be unique to each firm within our overall curricular goals.

The project is based on the firm’s experience with site constraints, program, construction, etc. and is designed to capture the richness of the firm’s work. The approach to solving the problem mirrors the firm’s design philosophy and process while providing an opportunity to reflect on its rationale and implications. The output of the process and its presentation reflect the firm’s experience in creating successful internal, peer, and client communications.

UCLA (1964): SUPRASTUDIO

Neil Denari, 2008-09 SUPRASTUDIO Director

“What’s next?” Although this meta-question encompasses all possible questions about the future of architectural education, within it is the implication that certain agendas have run their course and new ones must be initiated. Now that sustainability, in all of its forms (urbanism, materials, housing, natural resources, growth, etc.), has become, rightly, the lens through which the public discourse of architecture is perceived, “What’s next?” suggests a series of other questions: “What is the future of urbanism?” “What is the language of a sensitive, logic-based architecture?” “What exactly is cultural sustainability?” “How can architecture affect energy policy in the U.S.?” . . . and so on.

These and similar queries prompt an exhortation to schools to “Get Real, Get Public,” to leave the free fall of the digital field for a focus on applied research and the problems that face us as a global society. It is not yet clear, however, what will be the actual role of design, in contrast to the point-based logic of environmental assessment.

To address these questions, UCLA Architecture and Urban Design established a post professional degree program in 2008 entitled SUPRASTUDIO. Designed for M. Arch. II students, it centers around Los Angeles based sites, programs, consultants, and client sponsors, all of which come together in a dedicated curriculum that includes studios, technology and theory seminars, and field research in various cities. More akin to a one-room schoolhouse or the European Unit system, the year is written and taught by one professor with a fulltime assistant, with invited experts forming an expanded faculty team.

SUPRASTUDIO takes advantage of UCLA’s rich recent history of advanced design and reaches for new levels of interactivity with companies and agencies whose work or products affect both L.A. and our lives. SUPRASTUDIO’s agenda is to confront what is now a collective problem—that of the sustainable future—with a sensibility that does not create adversarial relationships between design and responsibility, between aesthetics and the anodyne, between academic and professional realms, or between the commercial and the avant-garde. Each year endeavors to develop ideas that are both speculative and rigorously real.

The 2008-09 year collaborated with Toyota Motor Sales, U.S.A., Inc., to explore the ways transportation and urban form can come together in large-scale undeveloped regions of Southern California. Entitled “Megavoids,” the studio designed a series of projects of enormous scale (both in form and population den sity) that challenged the pro forma of low-density sprawl without recourse to familiar urban models. This work allows Toyota to imagine its future as a transportation solutions company as they look to a peak oil time frame of 2025 and beyond. Field research was carried out in Vancouver (the most livable city in North America?) and Tokyo (the most chaotic with the most order).

For the 2009-2010 year, Professor Greg Lynn and Walt Disney Imagineering studied entertainment and the spectacle of physically immersive environments. Not usually associated with an academic enterprise, this constellation of figures and forces introduced a new conversation on design engendered by the programs of themed environments. Disneyland/Disneyworld has been theorized for years, but this was the first time that design research produced at a research university would have an impact on Walt Disney Imagineering’s design department. Pritzker Prize winner and Distinguished Professor Thom Mayne will lead the 2010-2011 academic year. In collaboration with the RAND Corporation, this SUPRASTUDIO will explore the intersection between cultural initiatives, public policy, and urban design, culminating in a comprehensive cultural plan for a selected city. For more information, see www.suprastudio.aud. ucla.edu.

Right, Roof Raising: Cal Poly Pomona third year B.Arch. and second year M.Arch. students and faculty raise a poured reinforced concrete roof in the department’s comprehensive studio.

Cal Poly Pomona: Shaping California’s Future

Michael Woo, Dean

California’s rise to global prominence in the second half of the 20th century was propelled by the state’s trail-blazing Master Plan for Higher Education, adopted in 1960, which opened up opportunities for many young Californians to become the first in their families to attend college. Subsequent decades of prosperity and economic expansion have proven the wisdom of staking California’s future to the public higher education sector.

At Cal Poly Pomona, design education has been a key part of the university’s service to the public. Building upon the polytechnic philosophy of “learning by doing,” the Architecture Department grew as it attracted prominent architects and designers such as Craig Ellwood, Ray Kappe, Richard Saul Wurman, Thom Mayne, and Marvin Malecha to join the faculty; and as it welcomed practitioners such as Richard Neutra and Raphael Soriano, who may have been too busy to teach but came to the campus regularly to critique student work.

As its graduates became known for acquiring practical, employable skills, the department evolved a distinctive role, especially in Southern California, where many of its alumni became stalwarts of the profession. And its high academic quality and low cost to students have made admissions extremely competitive.

But the steady erosion of state support for public higher education threatens the department’s achievements. Prominent faculty may consider moving to more financially stable institutions, and rising costs will close the door on students who cannot afford the unsubsidized cost of a high-quality, professional education.

Yet, even a severe, multi-year fiscal crisis cannot hold back the creativity of the department. For example, over the past three years, department faculty have collaborated with faculty from the highly-regarded Civil Engineering Department to teach an innovative studio offering architecture and engineering students a rare opportunity to work together on the design of a wooden bridge connecting two buildings on the campus. Led by Architecture Chair Judith Sheine and Professor Gary McGavin, architecture students have come to appreciate engineers’ thinking processes in ways that will serve them well in the real world.

Although budgets are tight, and the university’s bureaucracy does not make it easy to forge collaborations between departments in different colleges, the value of the experience over three years has convinced both Architecture and Civil Engineering that the relationship needs to be solidified and expanded, even if it requires raising external funds.

In another example of raising external funds to create opportunities for students and faculty to interact with industry professionals, the Architecture Department organized a Building Enclosure Sustainability Symposium earlier this year in collaboration with the engineering firm Simpson Gumpertz & Heger, Inc., with additional support from HMC Architects and other firms.

In addition to the ingenuity of faculty and students, the department has two other notable assets upon which to draw in response to external challenges. First, with Los Angeles County’s infill development to the west and the rapidly-urbanizing Inland Empire to the east, the campus is well-positioned for case studies, pilot projects, and client relationships, which are especially relevant to our growing emphases on sustainability and preservation studies.

Finally, the most striking factor may be the student body’s ethnic and cultural diversity, with high percentages of students who were born in another country, learned English after starting out in another language, or are the first in their families to earn a college degree. Opening doors of opportunity for those striving to enter the middle class has been the historic mission of public higher education in California. But for a program that aims to produce the architects who will shape our environments, the daily diversity of life at Cal Poly Pomona is truly emblematic of California’s future.

SCI-Arc (1972): So We Opened a Gallery

Eric Owen Moss, Director

Krishna once admonished Arjuna:

“…not fare well, but fare forward, warriors.”

SCI-Arc was listening.

So we opened a gallery.

Here’s the SCI-Arc conundrum: in a tradition of non-tradition, in search for the perpetual experiment, on the lookout for a pedagogy that hasn’t yet been discovered, SCI-Arc aspires to teach what it doesn’t yet know.

How can you teach what you don’t know?

So we opened a gallery.

What we don’t know is the destination of the architecture discourse.

But we understand where to look.

So we opened a gallery.

What we know is our intention.

We intend to begin again, and again, and again.

We intend to sustain the fragile idea, the tentative thought, the preliminary sensibility, the not-altogether clear hypothesis.

We intend to disestablish.

So we opened a gallery.

SCI-Arc teaches intent: the wonder of wondering, one architect at a time.

Imagining architecture’s Magellans: lost and found, and lost and found again, one architect at a time.

So we opened a gallery.

What’s durable is the intellectual and emotional toughness of SCI-Arc’s critical pursuit.

Not intellectual Darwinism, with gradually evolving chronologies of thought.

More a cataclysmic evolution of thought moving by twists and leaps.

So we opened a gallery.

Magellan’s circumnavigation was never guaranteed.

But the means were available, and the end was plausible.

Ditto SCI-Arc. [Although Magellan himself didn’t make it.]

[And that makes sense to us too.]

So we opened a gallery. SCI-Arc doesn’t own invention.

What SCI-Arc guarantees is a mind-set of discovery.

Independence, idiosyncrasy, self-confidence.

And that mind set makes invention at SCI-Arc plausible.

Not the durable ends, but the durable means to evolving ends.

It’s the process of imagining that’s compelling. Or more precisely, the pursuit of what doesn’t yet exist.

So we opened a gallery.

Why?

Not long after its birth, the new, once fragile, now less new, no longer fragile, is codified— doctrine, books, has advocates, teachers, becomes an allegiance.

A codex. If there’s a code, there’s a map.

If there’s a map, there’s a route.

If there’s a route, It’s the post-codex institute.

SCI-Arc is the pre-codex institute.

That’s the enduring aspiration. So in 2002 we opened a gallery.

NewSchool: Serving Education, Addressing Need

Steve Altman, President

NewSchool of Architecture and Design (NSAD) students are making a difference in the real world from San Diego to Monterey to Liberia through participation in Design Clinic. As a continuing opportunity in the curriculum, Design Clinic has provided master planning and preliminary design services to individuals, the underserved, and disaster victim groups and community partners for the past decade.

Started under the guidance of Graduate Program Department Chair Kurt Hunker in response to the damage caused by local wildfires, the program has grown significantly as it has gained visibility in the past few years. Now under the purview of Associate Professor Chuck Crawford and Adjunct Professor Adriana Cuellar, this course allows NSAD to give back to the local, state, and—increasingly—the global community, while affording students the opportunity to test their planning, design, and communication skills outside the classroom. They learn how to deal with the intricacies of ill-defined projects, diverse clients, and the necessities of teamwork.

The projects range from a 600 square foot thrift store renovation benefiting single mothers to a 200,000 square foot automotive museum. Gateway San Diego, an Intermodal Transportation Center Proposal under the direction of NSAD Board Member Jim Frost, was the recipient of the 2009 San Diego Architectural Foundation “Orchid” for planning excellence.

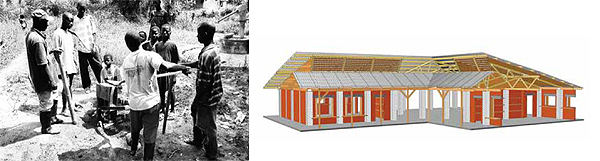

The clinic’s most ambitious project is the Morweh Educational Institute (MEI) in Liberia, Africa (http://www.morweh-edf.org). A self-supporting village on 4,000 acres, it features indigenous construction materials and techniques, passive heating and cooling, and a phased construction plan for classrooms, housing, dining and worship facilities, sports fields, and food production, including farming, livestock, and a fishery. This summer, the residents of Morweh began pressing natural mud bricks and digging foundation trenches, and construction is scheduled to begin in December. NSAD student Paul Davis was awarded a scholarship from the Morweh Educational Institute Foundation and will be traveling to Liberia after graduation to assist in the on-going design and construction of the Institute.

Meanwhile, this August, students Miguel Abarca, Yousef Al-Rashed, Allen Ghaida, David Mandel, Lynn Ritz, and Ramiro Saenz presented their models and drawings to over 300,000 auto enthusiasts attending the annual Monterey Automotive Week. The Monterey Automotive Heritage and Preservation Foundation is using this material to obtain entitlements and funding for the most ambitious automotive museum and educational and restoration center in North America.

NSAD students have provided homeowners devastated by wildfires the documents necessary to rebuild their homes; they have worked with non-profit advocates for the homeless to research and interpret building and zoning codes; they have proposed options for transit stations at UC San Diego and a community village and gateway at San Diego State University; and they have advocated on behalf of an award-winning transportation hub that would bring together automobile parking, bus lines, surface light-rail trolleys, Amtrak’s “Coaster,” and San Diego’s Lindbergh Field, all contained under a new urban park at the edge of San Diego’s bay. Current projects include a collaboration with estudio teddy cruz to design prefabricated room additions for low-income residents of San Ysidro, a gymnasium for the YMCA, and a “net zero” care-taker residence for a dog rescue shelter in Texas.

This is (or should be) the mission of every school of architecture: making our communities better places to live and work on both a local and global scale. Our students learn by doing, and the excitement and satisfaction from their experience propels them to want to do even more.

For more information visit: www.newschoolarch.edu/designclinic.

Woodbury University (1984): Fieldwork Transforms

Norman Millar, Dean, and Vic Liptak, Assoc. Dean

Fieldwork is a state of mind, a consideration of the world as laboratory, of lived experience as archaeology. Through fieldwork, we address urgent issues grounded in reality and contemporaneity. The Woodbury B. Arch. Program has extensive opportunities for students to immerse themselves in architecture away from campus. Faculty lead programs in Barcelona,Berlin, India, Tahiti, Colombia, Costa Rica, Buenos Aires, Nanjing, Paris, Rome, and the American Southwest. Students also take advantage of exchange programs in England, Spain, Germany, Mexico, and South Korea.

Fieldwork as ethos permeates Woodbury Architecture’s new issue-driven master’s curricula, engaging local Southern California territories, distant learning sites, and unexplored academic terrain. The diverging and intersecting paths of alternative practice and entrepreneurship, landscape design and urbanism, and architecture and technology encourage advanced students to develop a practice of architecture with a focused expertise.

Woodbury’s School of Architecture offers programs leading to a professional B. Arch. Or M. Arch., a post-professional Master of Architecture in Real Estate Development or in one of three focuses described below, and a BFA in Interior Architecture.

The focus on Alternative Practice and Entrepreneurship challenges the architect to take a greater role in the development of the built environment, from infrastructure design to policy making to community advocacy and public art. For students who wish to follow their M. Arch. with an MBA, six pre-MBA courses in the School of Business may be taken as electives, allowing the M. Arch. Recipient to move directly into Woodbury’s one-year MBA program.

The focus on Landscape Design and Urbanism addresses the history of the city, urban and rural landscapes, contested landscapes, wilderness edge conditions, borders, energy and infrastructures, geography and watersheds, community design, landscape architecture, urban design, and policy and planning.

The focus on Architecture and Technology addresses emergent technologies and materials, green technologies, responsive environments, building skins and systems, mass production, prefabrication, rapid prototyping, and digital fabrication.

We maintain a critical, inventive, resourceful, and exceptionally dedicated faculty representing diverse interests and strengths. Faculty interests under development include research and design in response to US-Mexico trans-border conditions, and designing a landscape architecture curriculum toward a professional MLA degree. Three faculty initiatives have already attracted external attention and funding:

The eponymously-funded Julius Shulman Institute provides programs that promote an appreciation and understanding of architecture and design, focusing on Shulman’s enduring involvement in the broad issues of modernism in Southern California and the application of photography as a basic instrument for presenting and representing design.

The Center for Community Research and Design acts as a resource and research center for both real and visionary responses to questions about the future of the communities of Los Angeles. Its public art and architecture work in universal design are supported by the NEA.

The Arid Lands Institute (ALI) is an education, research, and outreach center addressing water scarcity, increased hydrologic variability, and climate change in the arid and semi-arid American West. ALI received a $600,000 grant from HUD in 2009 funding three years of research, development, and educational opportunities in collaboration with communities in Burbank and Embudo/ Dixon, New Mexico, and culminating with a two day conference in 2012 on Best Practices in Dry Lands Design in collaboration with the California Architectural Foundation. ALI is developing a fellows program to attract scholars who will further the institute’s work.

California College of the Arts (1985): Architecture Labs

Ila Berman, Director

The architecture programs at CCA promote the understanding of architecture as a critical and rapidly evolving practice within a larger cultural context. In addition to providing students a firm foundation in the profession, they offer specialized areas of investigation supported by three exploratory labs focused on digital technologies, urbanism, and ecology. Each lab consolidates advanced research expertise around project- and studio-based activities, which are then shared through public workshops, exhibitions, lectures, publications, symposia, and other events. The labs intensify areas within the curricula, through the provision of core and elective course offerings; they form, as well, the locus of research for our new interdisciplinary, post-professional Masters in Advanced Architectural Design (MAAD).

The MEDIAlab (mlab.cca.edu) integrates the interdisciplinary culture of CCA with our region’s cutting-edge digital milieu. It advances skills and research in generative design strategies, parametric modeling, scripting and computation, building information modeling, digital fabrication, advanced visualization, robotics, and interaction. These rapidly advancing technologies will continue to transform the ways in which we design, build, and think about architecture and will have one of the largest influences on the evolution of the profession in the hands of the next generation. Research projects and events mounted through this lab include the exhibition FLUX: Architecture in a Parametric Landscape, lecture series and workshops coordinated with the 2009 International Smart Geometry Conference, and Biodynamic Structures—an intensive workshop investigating the application of dynamic energetic processes in living systems to environmentally and materially responsive building structures and skins—co-developed with the Emergent Technologies and Design Programme at the Architectural Association in London.

The URBANlab (ulab.cca.edu) investigates the design challenges and potentials of the urban environment in the 21st century. Supported by the lab, our new post-professional program in this area integrates organizational, systemic, and morphological investigations in architecture and urbanism with urban geography and landscape design. Developing projects that operate on the local, metropolitan, and regional scales, this lab engages the realities and transformative potential of the post-industrial city and explores future urban ecologies and their architectural and infrastructural systems. Such projects as Transformative Land: Envisioning Bay Link Pier 70, focused on the redevelopment of the San Francisco waterfront, and Agropolis, dealing with the overlay of urban agriculture and architecturally embedded systems for energy harvesting, represent examples of the lab’s endeavors. Global-scaled research on international cities and their environs, such as Jerusalem: Divided City/Common Ground, and research projects in Shanghai, Taiwan, Vienna, Berlin, and Buenos Aires, are supported through travel studios and collaborative workshops.

The ECOlab (elab.cca.edu) focuses on environmentally responsive architectural systems and ecologically informed design strategies. Recent projects include the Refract House, first-place winner in the architectural category of the 2009 Solar Decathlon, designed in collaboration with Santa Clara University; the Sustainable Skyscraper: Vertical Ecologies and Urban Ecosystems studio; and the Networked Urban Sensing project, a partnership with geographers and meteorologists at SFSU that develops architectural and urban systems in response to the measurement of city-scaled microclimates.

Digital technologies, global urbanization, and ecological imperatives are three critical domains guaranteed to have a tremendous impact on the ways we practice architecture in the future. Architectural educational institutions must be the place where such design research and innovation occur in ways that are highly integrated with, yet have some autonomy from, the daily structure of our professional curriculum.

Academy of Art University (2001): Meaning and Making

Alberto Bertoli, Director

The Academy of Art University was established in San Francisco in 1929 with a philosophy of building a faculty of established professionals to teach future professionals. The AAU began preparations for an Architecture School in the year 2000 and launched its graduate program in the fall of 2001.

Since its inception, the architectural program at the Academy has been under continuous academic development with the intent of educating future design professionals capable of critical thinking and service to both society and the profession. The program teaches students the fundamentals of the architectural profession and, through the exploration of Meaning and Making, exposes them to the continual historical unfolding of architectural ideas—from classical times through today—and the factors that influence design: aesthetics, technology, urbanism, media, and social behavior.

The School of Architecture at the AAU strives to achieve a balance of focus in theory, technology, history, practice, media, and sustainability and at all times to encourage a synthesis of these areas in the process of design and aesthetic discourse. Fixation with the fashionable is dismissed in favor of a genuine and vigorous creative pursuit and a methodical investigation of architectural possibilities. Siting, planning, programming, selection of materials, and even detail development are components of a conceptual investigation used to understand the formation of architectural Meaning. Design studios are the core of the curriculum and the forum for this continuing discussion. Starting with the analysis of case studies, students develop a personal architectural language that they can augment over the course of a progressive studio sequence. The gradual introduction of studio topics such as sensory systems, site analysis, and the technical and aesthetic importance of structural systems culminates in a comprehensive studio that is a precursor to a two-semester thesis period.

Communication of an architectural thought is encouraged through all available graphic media and techniques. While a comprehensive set of digital resources (emulating those found in the profession) is made available and supported in the curriculum, hand drawing remains a vital component in the generation of design ideas. Craftsmanship is considered a priority, and drawing is emphasized as a tool for both representation and exploration. Similarly, the practice of physical model making is incorporated not only as a representational tool and a mechanism for developing craftsmanship, but also as a design strategy for the generation of form, space, and composition, emphasizing the importance of the concept of Making.

A unique component of academic life at the AAU is the interaction across multiple disciplines of art and design. Selected studios offer collaborative projects in which participation from students enrolled in other programs (Industrial Design, Sculpture, Painting, and Interior Design) provides a cross-fertilization of ideas and uncovers mutually enriching information and processes—an early introduction to the type of teamwork that is critical to the architectural profession.

At the completion of the program, students presenting their final theses are required to extend their field of study and learn to represent their thesis idea in a painting. More than the acquisition of an additional graphic skill, this step involves stretching the student’s notion about the boundaries of their discipline and enhancing their ability to communicate an idea regardless of the media used.

As an extension of the curriculum, the School of Architecture is involved in two major events during the academic year. In the fall, a visiting moderator leads a public symposium, in which a panel of professionals, students and guests debate a pre-determined architectural topic. Each Spring, a visiting professor leads the Visionary Charrette—involving all students in a week-long effort proposing solutions to an urban project located in San Francisco. The Charrette culminates in a public debate in which students must defend their proposals. It is the intent of the school to publish these events at regular intervals and use them as theoretical material within the curriculum.

Originally published in arcCA 10.3, “Design Education.”