The world seems obsessed these days with change; change in the ways we think, communicate, use our time, allocate resources; change in the ways we build; change in what we like … change in what we are like.

Not so long ago our fascination was with endurance: with stone, with constants, with classical, irrefutable form, with wholeness and with familiarity … with things that outlast change, relationships that endure.

There is an English colloquialism that refers to the need to keep up with change. One is urged to “stay with it”—to sail on the winds of change, or go with the flow. It is a call to be current, to know and absorb (and preferably to exceed) the latest developments in the field, or, more trivially, to know the hot gossip. Many of our colleagues consider this the supreme imperative. In this they are urged by the media and by the ethos of competition—by the thirst of the market, that great greedy god of the times. Staying “with it” can be exhilarating: it can also be a desperate enterprise.

Curiously the same words, “stay with it,” used with different emphasis, an emphasis on the “‘stay,” can be a call for endurance, an instruction for how to achieve things of lasting value.

Of course the two are not altogether in conflict—real invention comes from staying with a problem long enough, entering into it deeply enough, to find new relationships For the endurance we seek is of the world, not removed from it. It is embodied in the times, but securely so. We seek an endurance that can be of significance to the community that is inclusive, not ephemeral.

The difference between the two meanings of the phrase “staying with it” lies not only in the emphasis, but also in what is signified by “it.” In the trendy term, “it” refers to time, to the zeitgeist. In the call for endurance, “it” can refer to place, or perhaps more fundamentally to principle: to a conception or a problem that bears continued exploration.

The endurance that must matter to us, as architects in this era, is an endurance that gives continuing coherence and sensible structure to communities that are in continuous change. The endurance of stone still has its place, obviously: it provides material permanence that resists decay and casual transformation. Invested with mental pattern, stone creates fixed points in the flux of transformation that anchor our minds and hearts to a place and—as in a shrine—structure daily acts of devotion or improvisation. Stone structures that outlive their motivation often evoke new uses and patterns—but only those stones that have been invested with significant traces of human imagination. The same is true for places built with lesser materials.

More ubiquitous, or extended, forms of endurance are established by the streets, property lines and urban services that define the districts of a city (or a village). These give rise to the patterns of building and the concentration or dispersal of uses and investment that characterize a city. They structure the common experiences that a city makes possible. Their endurance gives stability to a community and the nature of the transactions that take place within it.

These patterns, in turn, are usually related, often in subtle ways, to the underlying natural characteristics of the place and the customs and culture that evolved there.

For much of the last century it was presumed that these patterns were completely provisional—matters only of convenience that had no inherent value and were therefore easily subject to rearrangement. We now know—and the residents of cities know—that this is not the case.

The fabric of a city enters deeply into the psyche of its citizens; it helps to sustain their sense of community. Learning to know that fabric—the strands, nubs and textures of the streets of a place—and the way they are connected to a larger order—is a fundamental initiation to the culture of a city.

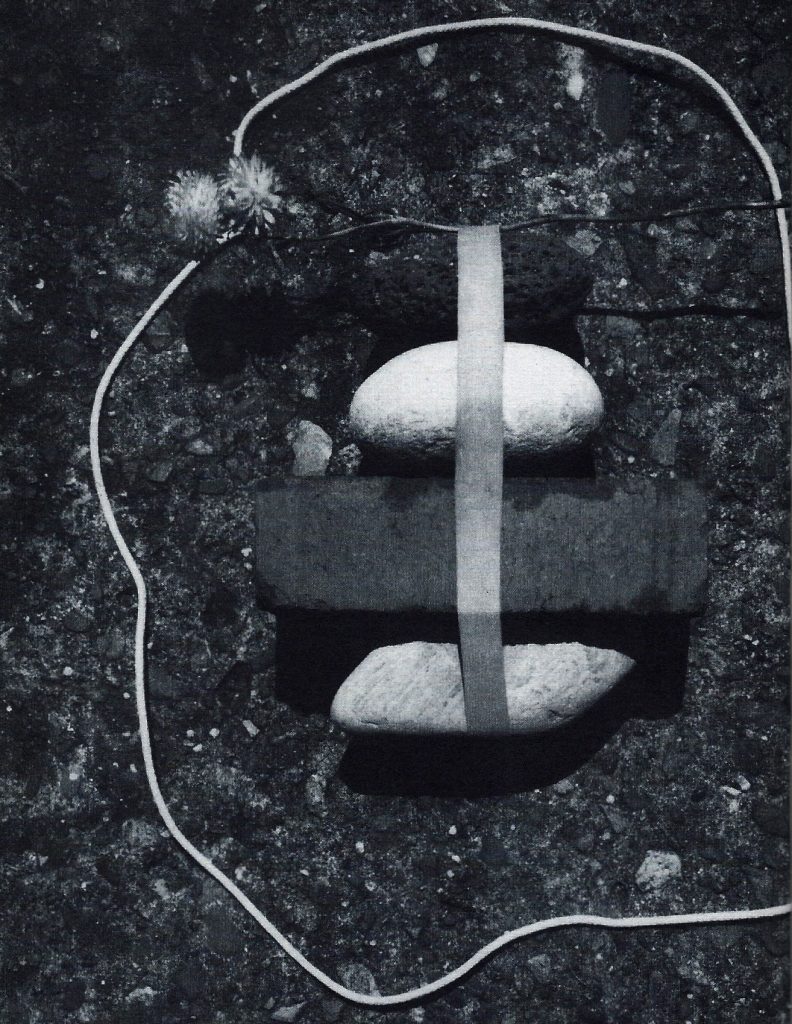

Places—spaces that you can recognize and call to mind—become reference points in a mental map that we can share. Like stones, though, they must be invested with human imagination if they are to endure. Even more than stones, places need constant investments of energy and care—of maintenance and reinvestment that attract and absorb the energies of change.

Good places are distinct, offer their inhabitants many choices, reward curiosity and attention and receive many types of investment, enduring and transitory (monuments and flowers).

To be distinct and memorable they are likely to incorporate a full complement of the elements of architecture. Platform, frame, canopy and marker, something to stand on, something to create and modulate borders, something to be under and something to be next to.

Venice, of course, does this exceptionally well—with its platforms underfoot, landings, passages and bridges that celebrate the miracle of being able to walk in the middle of the lagoon, with its rhythmic borders that play endlessly with syncopated pairs in a recognizable beat that most surely echoes in our blood stream, and with the array of little and large canopies and domes that break out of the fabric to house saints. With congregations forming parish landmarks that are articulated by towers and statues to measure your distance from—and with the great rooms that suddenly appear in the fabric of passages and gather all elements, even the watery reflective floor, into silhouettes against the sky.

Places that will endure change must be cared for by people who will attend to such things. We cannot any longer count on “native sensibilities” for change. Places need to recruit new companions, not confirm old habitués, and they need continuous, inventive care.

All this is a big order—the task we are setting for ourselves. As a simple offering, I suggest three of the many things we may do as architects:

- Stay with a place and a vocabulary and show that it can adjust to various conditions.

- Understand city fabric, invent vocabularies and new uses for the context, and articulate guidelines for their (changing) use.

- Reintroduce community leaders to the places they are responsible for and show them options that yet adhere to fundamental principles.

Author Donlyn Lyndon, FAIA, editor of the design journal Places and Co-author of Chambers for a Memory Palace, is a professor in the University of California, Berkeley, Department of Architecture. This excerpt from a talk given at the ILAUD (International Laboratory of Architecture and Design) conference in Italy is reprinted by permission of the author.

Originally published in early 2000, in arcCA 00.1, “Zoning Time.” Re-released in arcCA DIGEST Season 17, “Adaptive Reuse.”