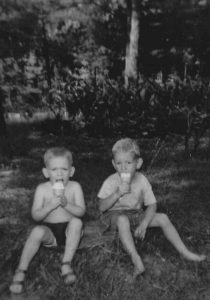

As we began to prepare for this issue, I corresponded with my oldest childhood friend, back in Tennessee: Tom Gibson, who has grown up to be a Methodist minister and semi-professional magician. Here is a bit of our exchange.

[Tim] The fourth quarter issue of arcCA this year is on “Faith and Loss”—religious and memorial architecture, but we’re also interested in stretching the boundaries; any interest in weighing in?

[Tom] How very thoughtful to pair the two. Sometimes loss calls faith into question and sometimes faith grows from, or at least in response to, loss. One of my favorite word-of-the-day entries from a calendar a decade or so ago is “cenotaph.” The Lincoln Memorial is one. I always thought it would be the perfect name for a church, “Cenotaph United Methodist Church.” Folks would ask, “What does that mean?” and I’d answer, “A memorial building dedicated to one whose remains are not there.” The stained glass in the narthex would be a depiction of the angels at the empty tomb, telling the women, “He is not here, but is risen.”

In the past few years, I have been drawn to labyrinths and their meditative properties. There is a bit of literature on walking the labyrinth as an exercise for letting go of loss, entering into the center of pain and working your way back out. You might look to see where some labyrinths are incorporated into architecture and landscape. Grace Cathedral in San Francisco has a Chartres labyrinth indoors and another on the grounds. California has a number of New Age versions too, but I don’t know the scope and range of architectural forms and variations you might find: http://labyrinthlocator.com.

[Tim] There was for a while in the architectural theory realm a notion referred to as “the presence of an absence”— the idea that you can shape a space in such a way as to evoke something that is not there. It got all hyped up and not much was done substantively, that I recall, other than academic posturing, but it is a potent idea; the obvious common example is an empty stage. A Dutch architect, Herman Hertzberger, says, less highfalutin’ly, that the building should be a pedestal; the people are the art; that, contrary to the way buildings are usually portrayed in the architecture press, they should give the feeling that something is missing if people are absent from the scene. I like that way of thinking about it, myself.

There’s a labyrinth in an old quarry in a regional park near us, and the kids like to run around it. In the rainy season, a shallow pond forms adjacent to it, where the newts breed. There’s a road up that way that they close every year for the newt-crossing season. I don’t know that the newts have anything more intentional to do with the labyrinth.

[Tom] Presence of an absence? A packed phrase, that one! That’s really what loss is about, now that you mention it. Not the absence of a presence; that would just be a void. A never occupied building may give that feeling, but a once-busy-but-not-now-occupied building would better convey loss, the lingering sense of no-longer. A pedestal topped only by the un-discolored circle indicating where the statuary used to stand, or perhaps the statue’s crumbling foot and ankle reaching up to the space left by the missing mass once above it, or the distant feet of a broken arch, parenthesizing open air. Loss isn’t just nothingness, but a feeling of no-that-thingness, like that ghost image you get when you stare at a spot then turn your head and blink; retention of vision, we call it in magic circles. Empty space can be very calming. Emptied space has an altogether different vibe.

Originally published 4th quarter 2010, in arcCA 10.4, “Faith & Loss.”