Take off something you’re wearing… look at the tag… look at where it was made… how do you think it got here?

Ports are crucial to our economic growth and wellbeing, our quality of modern life. From the time of our earliest settlements, they have provided a means to be supplied with goods (imports) and to collect goods for outside trade (exports). Originally thought of as rough, dirty, industrial areas, unattractive to commercial or residential development and utilization, ports today are considered desirable, vibrant components of the cities they adjoin. This paradigm shift has led to the competing interests of shippers and industrial users and recreational and commercial users vying for access to the same valuable lands. At the same time, the increasing size of port facilities raises important environmental issues. The conflicting needs of these several interests are being reconciled today with strategies for the future utilization of ports.

Ports require unique physical criteria: deep water adjacent to low-lying flat land at the edge of our oceans or rivers. This meeting of flat land and deep water is rare along the California coast. The topography of the coast limits the development of deep-water ports to a few areas, fixing the location of major industrial nodes. In California, the major ports with these characteristics are San Francisco, Oakland, Los Angeles, Long Beach, and San Diego. Other areas where these features are present to a lesser extent are Port Hueneme, Humboldt Bay, Sacramento, and Stockton. The Coastal Act limits port development to these areas, but, historically, the population/economic base along these nodes was the basis for port establishment and growth.

Originally, ports were mud flats served by small skiffs. Piers and wharves were developed to reach ships anchored in deep water to allow more efficient transfer of cargo to shore. Before the advent of containerization, ships were small. Cargo consisted of loose, palletized or break-bulk loads. Loading and unloading cargo were labor-intensive operations. Infrastructure requirements included finger piers, on-dock transit sheds, warehousing for storage, and rail lines, which influenced surrounding land use patterns. Due to the small radius of delivery service, a large amount of land was needed to service a port. Manufacturing and distribution districts (fisheries, shipbuilding, foundries, etc.) grew in close proximity to the waterfront, as did housing districts for port workers. A relatively small percentage of area was accessible to the general public. The traditional port environment was considered a most undesirable place to be.

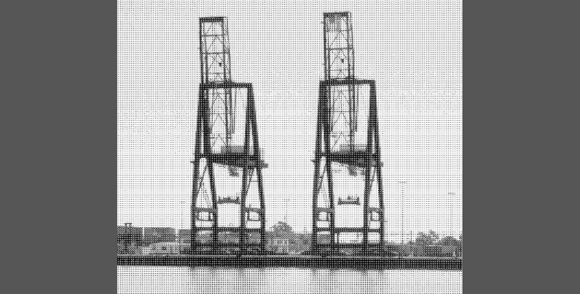

Containerization has significantly changed the characteristics of industrial ports. Break-bulk and palletized cargo have been superseded by universal cargo containers that are essentially self-contained ‘mini-warehouses’ for dry or refrigerated goods. Operations are now mechanization-intensive, not labor-intensive. Vessels are larger, requiring large concrete wharves operated by giant wharf cranes, forklifts, and mobile, rubber-tired gantry cranes that evoke images of Star Wars in all their articulated, robotic qualities. Covered storage facilities are no longer necessary; containers are now stored on large, outdoor, container “parking lots.”

Again, land use patterns are affected. Manufacturing and distribution can now be remote from the port, creating a large, extending radius of delivery service beyond the port and opening up the availability of port-adjacent land for other uses. Competing interests, at times with incompatible requirements, vie for this land. Wider cross-sections of people now live, work, and recreate in close proximity to ports. The demand for waterside access and amenities not specifically involved with port operations has increased, and interest grows for the restoration and adaptive re-use of warehouse and distribution districts. Such areas have been transformed into new waterfront commercial, housing, and recreational uses.

Environmental issues are also undergoing changes after containerization. Increased operations have led to tighter restrictions and tougher standards for air and water quality, to control the impact of storm-water runoff, vehicle and maritime emissions, and airborne dust. Increased truck and intermodal rail traffic brings additional crossing and freeway congestion, affecting near-port communities. Larger terminals are needed to accommodate larger cargo surges. Consequently, ports must create additional land area by filling between finger piers and out into portions of the bay, or they must remediate and reuse former industrial sites, such as oil fields and manufacturing areas. More cargo equals larger ships, which need deeper water, forcing most ports to dredge to accommodate the deeper drafts. In the face of such pressures, the preservation of sensitive environmental sites along with growth has become a major port policy issue.

Responding to the Paradigm Shift: the San Francisco Bay Ports

California ports have responded in creative ways to the forces applied by economic conditions and by public regulatory and environmental agencies. Continued growth of port cargo volume and the impact of potential growth in the Far East have ports scrambling for additional area for expansion. The Coastal Commission and San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC) play a major role in shaping future port development and waterside access projects, allowing increased input from diverse stakeholders. Competing interests for available waterfront land and the effect of new technology on land use distribution have affected land use patterns. In addition, the recent move from mechanization to automated/information technology will have a far-reaching effect on all facets of port operations, transportation systems, and labor utilization.

The forces directing growth in the case of the two Bay Area ports, Oakland and San Francisco, are increased cargo volume for Oakland (which has the advantage of easy rail and freeway connectivity) and maximum utilization of the waterfront for entertainment and commercial uses for San Francisco.

Port of Oakland

The Port of Oakland occupies 19 miles of waterfront on the eastern shore of the San Francisco Bay, with 665 acres devoted to maritime activities. It is in the midst of its Vision 2000 (V2K) expansion, the first step in a long-term plan to double the container terminal coverage from 500 to 1,000 acres, to meet regional and national cargo needs into the new millennium.

Since World War II, the former military base has restricted public access to the shoreline of the Middle Harbor. Recently, through the closure of the Army and Navy facilities, additional land has become available for expansion. The southern end of the waterfront development provides commercial/ office, entertainment, housing, and recreational facilities. Recent developments have focused on the adaptive reuse of warehouse and manufacturing facilities into offices and lofts. The north end of the waterfront contains the industrial port, intermodal rail yard, Middle Harbor, and the innovative Shoreline Park. The creation of the park, mandated by the BCDC as a condition of approval for the port expansion, returns the best piece of real estate to the public. The public will regain access to the San Francisco Bay, with magnificent views of San Francisco; Oakland citizens will have views to the working waterfront; and the environment will benefit from the creation of a new major habitat carved out of former finger piers.

Port of San Francisco

While cargo growth drives the Port of Oakland, tourism and recreation are the forces behind the development of the San Francisco waterfront. The port does, however, retain a small container facility, ship repair, and bulk cargo area at the southern end of the waterfront.

New waterfront development is strongly linked to the existing urban fabric through the reuse of former warehouse and manufacturing buildings, with plazas and open areas provided by new projects. The Embarcadero, a grand boulevard and esplanade, provides the connection to activities along the waterfront, which include entertainment areas, a cruise ship terminal, future recreational piers, and a ferry terminal and transportation node.

The common thread running through the two ports is the development of strong connections between the waterfront and nearby, “downtown” urban uses. Meanwhile, even though these are mature ports, enough adjacent land not in the downtown area has allowed for necessary expansion, and the radius of delivery service infrastructure has remained small, as in a pre-containerization port.

Overall, our California Ports face new challenges with precious few acres available for growth. Our ports are faced with finding creative solutions in the technology and land-use arenas to respond to higher cargo demands as well as providing waterfront access and amenities that respond to public and environmental needs. This new awareness of the waterfront is the beginning of a shift in the perception of desirability and necessity of developing urban experiences at our waterfronts.

Co-author Louis J. Di Meglio, AIA, is an associate at Jordan Woodman Dobson, an internationally known architecture and engineering firm in Oakland, specializing in maritime planning and architecture; co-author Lourdes M. Garcia, AIA, is Vice-President and Director of Design at Jordan Woodman Dobson and an adjunct professor at CCAC.

Originally published 4th quarter 2001, in arcCA 01.4, “H2O CA.” Photo of Port of Oakland by Marc Phu.