In an era of globalization—and of global misunderstandings—we cherish the collegiality of our profession, which spans political and national borders. arcCA has asked a dozen architects from around the world to tell us about the nature and conditions of practice in their home countries. Their replies not only provide insight into their lives, but also help us put our own joys and tribulations into a global perspective.

AUSTRALIA

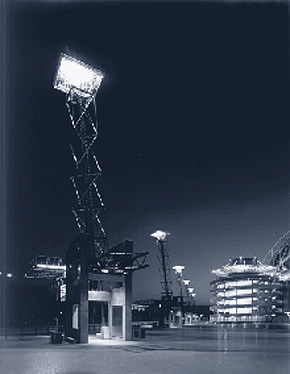

Peter Tonkin is Director of Tonkin Zulaikha Greer Architects, a 24-person firm in Sydney, Australia, whose award winning projects have included the redevelopment of the Hyde Park Barracks Museum in 1992; the Vietnam Memorial, Canberra, 1993; the Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre, 1996; and the Public Domain and solar-powered Plaza Lighting Towers at Sydney Olympic Park

A recent and authoritative poll by the National Trust of Australia counted the 100 “Living National Treasures” of Australia. None are architects, and only five are involved in the visual arts. Dominant are sports and community figures and performers. This probably reflects the real perception of architects in Australia: as not all that important, except when to blame for the eyesore next door. A few current and historical architects stand out for their public presence; the Sydney Opera House’s (non-Australian) Utzon is a household name, while in each major city a handful of architects, alive and dead, would be recognized by most. Well-loved—or hated—built works are the foundation for a public profile, rather than critical acclaim or published writing. Given Australia’s still-present reliance on overseas opinion on many matters, international recognition is a fast-track to local celebrity, while consistent genius over a career can bring an often-posthumous fame.

Recently, however, in the booming property market, the ‘branding’ of apartment buildings by their designer has become common, and a largish group of architectural practices is ‘marketable.’ These firms share a range of prominent and successful built works, a fashionable style, and a defined image. The fact that under the gloss of the latest trend lies sound functional design, good workable spaces, and better than average built quality is unsaid, but it is the real message. These architects are recognized as leaders of taste and affect the overall quality of development in the inner city, leaving suburbia in its usual design vacuum. This trend has been confined to the booming eastern cities—Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane. The other state capitals and the regional centers lag, while the ‘bush’ sees little property investment and less focus on good design.

The Royal Australian Institute of Architects lobbies intensively the three levels of government in Australia—federal, state, and local—and is sometimes listened to. The RAIA tries t o forward the role of the profession and to influence decision making on construction policy, heritage preservation, environmental standards, and the supply of housing. Individual architects find a voice in the press on issues of design and city building, generally as quick ‘grabs,’ not reasoned comments. There are few votes in good architecture, and the time taken for the construction of buildings means that few governments last long enough to get the credit or blame for their design choices. Australia has had a few architect politicians, but not many, and most of them at the local (city) government level. A recent prime minister was noteworthy for his passion for 18th century architecture, but it was a source of satire, not respect, and distanced him from many voters.

Relations among client, architect, and builder vary as much as the situations and personalities. As ever, good buildings rely on a shared commitment and vision and a collaborative approach. Package deals where clients are offered a firm price by a collaboration of architect and developer/ builder are falling from favor due to poor built quality and low levels of control by clients; the best buildings are still procured by relatively traditional client/architect relationships, with good control of building contracts. Architectural competitions are seeing a revival, with several excellent completed results in recent years. The Sydney City Council requires limited competitions for inner-city buildings to foster “design excellence.“

In summary, architects seem to be earning back some of the public esteem lost in the mid- to late-twentieth century, by a combination of better design practice, savvy marketing, and improved public presence. The future does not look too bad.

AUSTRIA

Silja Tillner is principal of a five-person planning and urban design firm in Vienna. She received the Bauhaus Prize for her design for the URBION project for the revitalization of Vienna’s 6km long Gürtel Boulevard. She has also received awards for the retractable membrane roof for the Vienna city hall and for the membrane roof at Vienna’s Urban-Loritz Platz.

The Cost of Being an Architect

The procedure for becoming a licensed architect in Austria is similar to the US; it is required to first pass a licensing exam. After passing the test, one has to join the architects’ association and is liable to subscription in the “retirement fund,“ the “death fund,” and professional liability insurance, as well as being required to pay yearly subscription fees. These mandatory contributions are extremely high. They are calculated as a percentage of income and result, in some cases, in payments as high as 50 % of income. These fees burden especially smaller offices or younger colleagues at the beginning of their careers. There are no exceptions to these rules.

Due to European Union regulations, it is now possible for architects from any EU country to work in another EU member state. Several of the younger Austrian architects have used this rule to open up offices in Holland or Germany, where fees are very low (because there are no mandatory contributions except for administration), i.e., €500 / year compared to €12.000 / year based on a low to moderate income.

One of the big debates here among architects is how to reform the ridiculously expensive pension system. Younger architects would prefer to join the state system, which would allow for more flexibility, especially when changing jobs. The main disadvantage of the separate retirement fund for architects is the lack of flexibility; one cannot change profession or employment status without losing the contributions. This leads to the ridiculous situation that some architects who cannot acquire commissions still have to keep paying their dues.

The Architect In Society

Generally, architecture is a highly respected profession, associated with a lengthy and demanding education and a responsible professional life full of creative opportunities. One setback has been that building contractors are now allowed to call themselves “architect.“ Residential buildings, especially, are realized mostly by contractors who take over 95% of the architect’s design work, as well. Even if wealthy clients build sumptuous villas, very rarely do they consult architects.

By contrast, large public projects are always designed by architects. The public sector is the biggest client for architects in Austria, and respect for the work of architects is evident. Many responsible government officials have studied architecture or planning and value the creative contributions as well as the management qualities of architects. Lately, creative, appreciated architects also have been awarded with large projects. Formerly, only commercial, mediocre offices were trusted with large public buildings.

Architects are never elected to public office, and they are hardly ever consulted on government policy decisions with one exception—the building code—where usually one or two architects are consulted, but too little, and these are not “design architects.“

In the newspapers, architects are often portrayed as hip trendsetters, always wearing black and having a stern look on their face. They are definitely not perceived as leaders; only very few are trusted to be business people, as well. We are fighting this cliché of sushi-eating, fashion gurus, and would much rather be respected team members in all aspects of building technology and client relations. And many of us are just that!

Acquiring Commissions

The award of contracts in the public sector i s highly regulated and above a certain threshold always results in some form of competition. If the building costs exceed ¤5 million, the competition has to be open to the entire EU. Large private projects in an urban context that are anticipated to cause discussions or need variances for approval almost always are awarded through invited limited competitions.

The open competitions are currently inundated with German participants, due to the major building slump in Germany that has arrived after a decade-long building boom. The 1990s inspired many young architects to open up new offices in Berlin and other cities; they are now out of work.

Similarly, in Austria, studying architecture became extremely fashionable in the last decade, and many young graduates opened up team offices. Now there are by far too many architects competing for work, so it has become more and more difficult to succeed in a competition. The average number of competitions an architect has to participate in before winning a contract lies between 40 and 60. Each competition can easily cost an office around €15 — 20.000.

Yet the open competition is still the only tool for inexperienced architects to win a larger contract. If carried through in a fair and correct way, a competition seems like the perfect instrument to find the highest quality design. Lately, competitions have caused a lot of public debate, due to unfair procedures in which jurors have helped their friends win a project.

Another problem is that the jury often consists of extreme personalities: client representatives who seek functionality, business executives who require economic feasibility, city officials, several architects who demand an inspired solution but often have diverging opinions. The result is unfortunately agreement on the lowest common denominator, quite often a banal solution.

Comparison of Urban Design Tasks and Challenges

Today, in the US and Europe, master plans are no longer only product, but also process: consultation with stakeholders, public participation, project financing, and strategies for implementation have become as important as the use, height, and bulk of buildings. In US cities, the abundance of left-over space is in clear contrast to the shortage of public space, i.e. plazas, parks, and left-over spaces usually become areas of conflict. The lack of communal space, combined with car-dominated streets, leads to an absence of communication in public areas. In European cities, there is comparatively much less residual space, with the exception of brownfield-sites, which have become a main target of inner-city development projects in London, Frankfurt, and Vienna.

A more process-oriented work method has evolved in Vienna recently, with stronger community involvement and active citizen groups engaged in a participatory planning process. In the US, especially in Los Angeles, my experience showed that community involvement has a much longer history and has become an integral part of any planning project.

CHINA

Duanfang Lu and Gang Gang are principals of GZ Architects, Ltd., a fifteen-person architecture and urban design firm in Beijing, P.R. China.

Architecture is among the most respected of professions in China. Architects are admired by the public, who think they are talented, creative, artistically sensitive, and technically knowledgeable. In film and novel, architects are depicted as intellectuals, heroes, leaders, or romantic lovers. In reality, architects are well-to-do professionals compared with most wage earners. Average incomes of architects are upper middle class, better than what attorneys, doctors, and accountants earn. In particular, those who run their own design firms earn large incomes and enjoy costly lifestyles.

While, in the past, most architects worked for large, state design institutes with hundreds of employees, more and more now work in private firms. Most state institutes are interdisciplinary and offer services ranging from architectural design to structural engineering and housing technology. Small firms often need to collaborate with large institutes on making implementation plans.

Architecture in China is a powerful profession. Architects are consulted by local governments on matters of urban development; some serve on important boards and commissions and help shape space-related public policy. In most cities, at least one of the vice-mayors is from the architecture or urban planning discipline. Famous architects gain public recognition and are respected by a constituency outside the realm of architecture.

Architects play a comprehensive role in the building process. They interact with clients, make designs, prepare drawings, help clients obtain approvals from planning departments, offer guidance for the construction team, modify design in the building process, and inspect the contractor’s work. Some clients are more manipulative than others: they would like to select the builders, the materials, and the equipment without following the architects’ suggestions. But, in most cases, architects cooperate with clients and builders to make decisions during construction.

As China is in the process of rapid economic growth, investment is vast and architects are busy. Our firm, GZ Architects, for example, is a mid-size design firm (15 architects). We have frequently received commissions for large-scale development projects, including a 3 million sq. ft. residential complex in Chengdu (2000-2002) and a 2.6 million sq. ft. office complex in Beijing (2002-2003). At times we could not find enough qualified designers or drafters to do the work.

Despite these advantages, architects periodically suffer from disappointments and failures. Some clients are rude and lack education. Quite a few, including some large developers, are not reliable in terms of paying service fees. Several years ago, for instance, an architect who received his training in the US and won many national competitions designed an interesting house for a very successful real estate developer. Although he asked for a very modest fee (about US$1,000), the developer only paid half of the fee in the end. In addition, due to policy changes or financial problems, projects often start and pause abruptly. For firms with only a few commissions at hand, the risk of not having work is high.

Although many architects have the talent to do challenging work, they are frequently forced to sacrifice ideals by doing banal and architecturally unpromising projects, due to severe economic constraints. Local construction technology limitations also restrain the range of possibilities. When the expensive and monumental projects do come out, including some government-sponsored projects, clients often choose to give commissions to established Western architects in order to project a modern and prosperous image of the firm or the city, even when they can find local architects with similar talents. This gesture reveals a lack of self-confidence and the nation’s persistent belief in the superiority of exports from the developed world. Frantz Fanon’s classic depiction, in The Wretched of the Earth, of psychological violence in the context of the colonial situation could just as easily have been applied to the present mentality in China: “The look that the native turns on the settler’s town is a look of lust, a look of envy; it expresses his dreams of possession—all manner of possession.…” How to adjust this mindset and carve a larger space for their creative impulses is the task today’s Chinese architects confront.

ENGLAND

M.J. Long is Senior Partner of Long & Kentish, a twelve-person firm in London, England. Prior to founding Long & Kentish in 1994, she was a partner for twenty years with Colin St.John Wilson & Partners, where she was co-designer of the new British Library. She teaches regularly at the Yale School of Architecture.

Architects are in a somewhat anomalous position in England. The British educational system has always played down the visual arts. Words and music are both taken very seriously, but visual matters are not seen as a discipline, and architects’ views on matters visual are not seen as any more reliable than those of the “man in the street.“ Perhaps they are even seen as less reliable, because they are suspected of having been brainwashed by the Corbusian theories that are held responsible for the worst of the London housing estates and highway schemes.

There is also a traditional tendency in Britain to regard “trade,“ and therefore businessmen, as not quite respectable. The country was run by country squires for so long that, even now with most of the population living in cities, anyone in business is likely to be regarded with suspicion.

So, if they cannot be regarded as artists or businessmen, architects must fall into the category of technicians. And this is certainly a longstanding theme in British architecture. Paxton was an ingenious gardener, and much in Archigram, Rogers, Foster, Grimshaw, etc., comes out of that tradition.

Architects here have in recent years lost their traditional role as leaders of the design and construction process. A building of any size is now in the hands of the project manager. Increasingly in Britain, universities and public bodies go to either design build or private finance initiatives to organize construction projects.

Architects are not traditionally part of policy making in government. The exception here is Richard Rogers, who has worked hard to win the confidence of the Labour Party. He is in a position now to be listened to, at least on general issues of policy. It is largely from his arguments, I believe, that the government has begun to encourage the use of brownfield sites for new housing and is willing to put public money into the decontamination that is required to do so.

One significant difference between practice here and in the US is the use here of quantity surveyors. When I first started practicing here in the late ‘60s, almost every project followed the traditional route of a lump sum contract based upon a Bill of Quantities, measuring every nut and bolt and hour of labor. This gave a document that ensured a detailed (and level) playing field for tendering contractors and which also established agreed rates for pricing any variations. Bills of Quantities are hardly ever done now; fast track construction, design build, and other forms of construction management have bypassed the Bill and left the quantity surveyor as general financial advisor to the design team. Many QS firms have now gone into project management.

I am a member of the RIBA, but I have also recently become a board member of the local chapter of the AIA. I am amused at the unconscious pose of cultural imperialism adopted by the local AIA members, most of whom seem to come from the ranks of the big (three initial) US firms. There seems to be an assumption that US firms can show the locals how to do it. In some ways, there is an admirable professionalism about the US projects, but, on the whole, they totally fail to pick up the quirks and local equivocations of the contexts in which they operate. British projects, by comparison, may be too quirky and equivocal, but in the long run I now feel that the attitude of responsibility for the local context (physical and cultural) breeds a healthy modesty.

FINLAND

Juha Ilonen is principal of Arkkitehtitoimisto Juha Ilonen, a one-person firm in Helsinki, Finland. He is the recipient of the Pietilä prize (1998), the Suomi prize, awarded by the State of Finland (1994), and a state scholarship for artists (1990). He is the author of The Other Helsinki, a book about the reverse face of the architecture in the city, and is chairman of the editorial board of ark, the Finnish Architectural Review.

“It’s not a profession, it’s a club.“ This is how, traditionally, Finnish architects have seen their line of work. We are few, and everybody seems to know each other. Work has been pleasure, not business, and weekends or holidays have been no obstacles for the fun. This semi-bohemian life is, however, changing. The increasing number of building regulations, the shrinking time schedules, the computers: these have all pushed the practice toward a more businesslike activity.

But still, we are far from the American way, as I understand it. Most Finnish practices, even the internationally most famous ones, are teams of five to fifteen people. There is not a hierarchy of junior and senior partners and what have you, and the practice is not firstly a money making machine, which just happens to deal with architecture. A few business-minded practices of fifty or so exist, but many practices only have one architect, who also takes care of bookkeeping, cleaning, and the like. This is how I have worked since 1989, after having worked in a handful of small practices for ten years.

Another change is felt in the wallet. The economic depression of the early 1990s hit us hard. When phones eventually started to ring, a new era was entered. A working, solid system of standard fees (so fit for a bohemian lifestyle) was considered a cartel and thus banned. As a sad result, architects found themselves competing with prices.

A Finnish architect is one of the designers in a team, each of them usually chosen by the client. The engineers involved each take full responsibility for their own designs. Yet the architect has the overall responsibility and has to see to it that the various solutions match with each other. This self-evident role of the “main designer“ was recently written into a new law. Very few architects’ firms include services for structural or other engineering or cost calculation.

One cherished side of the profession is the system of architectural competitions. There are many, and their true function is to choose the architect for the job, not to get PR or sponsors for the project. Invited competitions in a variety of forms are becoming more popular, but almost all major public buildings are still results of open competitions. 50 to 250 entries are submitted to each open competition, anonymously, and the jury always has at least two architects appointed by the Finnish architects’ union. And there is no dirty play. Finns are known to be honest. According to a recent study, we have the lowest corruption rate in Europe. For almost every established architectural practice, this system of open competitions has been the stepping-stone to the profession and to further commissions. Many winners have been students, and they have been given the job regardless.

As professional personalities, Finnish architects have a schizophrenic position between all-bohemian artists and strictly professional engineers, which gives us the chance to enjoy both roles. The general public is just as confused as we are. This Jekyll-and-Hyde role is seen in the way we look as some kind of a synthesis. We wear casual, black clothes. Some of us still wear the 1960s architects’ uniform, the black-and-white striped Marimekko shirt. An architect wearing a business suit and a tie is almost a joke (among architects).

Speaking of not wearing a tie, Finnish women architects have over a hundred years of history behind them, and they have almost an equal status with their male colleagues. In the masculine world of construction, many of them are still called “girls,“ but many also turn this insult into a clever tool. And yes, there are many architect couples.

Architecture as a form of art has a solid status in Finland. The shadows of our great masters are long and protecting. Yet, the general public is very unaware of what we are and how we work, or how to reach us, for many reasons. An unwritten law says that we may not advertise our practices. If you look at marketing in media, we are invisible. The Internet is changing a lot of this, but have a look at Finnish architects’ web sites (the few there are): how uncommercial can you get?

We Finns are quiet people, Finnish architects even more so. We don’t explain our work, and we seldom make our opinions heard in the media. Two architects are or have been members of Parliament, a handful have taken part in communal politics. Architects dealing with theories are extremely few. Wild or crazy “artist“ architects hardly exist. We seem to be rather down to earth and pragmatic, yet with a strong underlying sense for the basic qualities in architecture.

ISRAEL

Avigail Sachs was a project architect at Ammar-Curiel Architects, a fifteen-person firm in Haifa, Israel, from 1997 to 2002. She holds a B. Arch. from Technion, Israel Institute of Technology, where she has also taught in the Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning. She received a master’s from MIT and is currently a PhD student at the University of California, Berkeley.

Architecture and Politics: the Role of Israeli Architects

The multiplicity of roles architects can and do assume is inherent in the profession and poses problems for architects everywhere. In Israel, this multiplicity of roles has added significance, because architecture, or more specifically building, has repeatedly been employed as a tool in the bitter Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Architecture can no longer be divorced from its political implications. Israeli architects have, for the most part, remained silent about this link and its impact on their professional roles. A recent controversy, in which this silence was challenged, brought the dilemma to public attention.

Debate arose over an entry to the Architecture Congress in Berlin, commissioned by the Israel Association of United Architects (IAUA) from two young Israeli architects, Eyal Weizman and Rafi Segal. It erupted when the architects presented their completed project, a catalogue of articles and photo essays entitled A Civilian Occupation: the Politics of Israeli Architecture. The director of the IAUA, Uri Zerubavel, protested that the initial brief had outlined a balanced and comprehensive review of Israeli planning, while the finished catalogue focused one-sidedly on the settlements in the Occupied Territories. The association angrily rejected it and cancelled the submission.

Esther Zanberg reported the rejection in Ha’aretz , a daily Israeli newspaper, and the story then received attention in the international press. English publication included items in the Philadelphia Inquirer, The Guardian, and the New York Times. The authors of these articles followed Zanberg’s lead and, siding with the editors of the catalogue, described the cancellation as “harsh political censorship.“ This assessment avoids, however, a discussion of the opposing interpretations of the role of architects that inform both the compilation and the rejection of the catalogue.

Segal and Weizman’s catalogue is not only a critique of architects and their alleged complicity in political decisions, it is also a demand that they assume the role of critical thinkers and political activists and that, as their representative, their association should do so, too. This position is obvious not only in the content of the catalogue but also in the decision to invite Gideon Levi and David Tartakover to contribute to it. Levi writes a weekly column in the daily Ha’aretz about the situation in the Occupied Territories, and Tartakover is well known for his left-wing political posters, among the more recent one for the refusniks association, Yesh Gvul. Both have consistently used their professional media positions for political persuasion. Weizman, moreover, was quoted in the Philadelphia Inquirer as saying, “The settlers have their magazines and newsletters, we think this catalogue is a kind of balance in the public debate,” suggesting that their catalogue is directed at political groups as well as architects.

The IAUA was established only a few years ago in response to the marginalization of architects in the quasi-governmental Architects and Engineers Association. The IAUA founders felt they were only partially represented by this latter organization, where architects were excluded from important committees and government policy decisions. This marginalization was seen as part of a broad deterioration in the standing and viability of the profession in Israeli society. With the objective of restoring professional pride and strengthening the national standing of Israeli architects, the association has organized lectures, tours, and symposia and has gained recognition as the official representative of Israeli architects in international forums. In a society torn by politics, the taking of what would have been perceived as a one-sided position was expected to be detrimental to the association’s objectives. While Zerubavel noted that he personally agreed with Segal and Weizman’s political convictions, he explained to reporters that, “The association is an a-political organization whose role is to promote specialization and not to take a political position.“

The positions of both the IAUA and the catalogue’s editors are responses to the complex situation that Israelis, and architects among them, must confront daily. The controversy over A Civilian Occupation has only begun to outline the possibilities and implications of each position. In the international arena, this debate brought attention to the catalogue that it might otherwise not have received. Several months after the cancellation, Zanberg reported that the catalogue had been exhibited in Berlin and New York and that the editors had been invited to lectures and discussions. It is in the Israeli architecture profession and the four Israeli schools of architecture, however, that this debate must continue, so that in the future, in what one hopes will be better times, Israeli architects can assume a responsible and meaningful role.

ITALY

Pierluigi Serraino has practiced architecture in Italy and France and is currently a project designer at SOM, San Francisco. He graduated from the School of Architecture of the University of Rome ‘La Sapienza’, earned his MArch at SCI-Arc and his MA in History and Theory at UCLA, and is now a PhD candidate at UC Berkeley. Author of History of Form* z (Birkhauser, 2002) and Modernism Rediscovered (Taschen, 2000), his writings and projects have been published internationally.

For centuries, Italian was the language of high culture in European architecture. This historical awareness bestows on Italian architects, still today, an undisputed aura in the public consciousness. Judgments on design issues—whether theoretical or concerning artifacts—are the prerogative of the unchallenged authority of architects, who capitalize on this national legacy. Today, architects in Italy can be consulted on national television, be columnists in non-specialized tabloids, and translate the professional patois in a language understandable for the general public.

The conditions of architectural practice have, however, changed since the Renaissance grandeur. Specifically, the twentieth century marked a transition in the professional status and ideological commitments of architects. In Italy, the Fascist period was the stage for the last unified expression between nation state and avant-garde. Giuseppe Terragni, Adalberto Libera, Mario Ridolfi, and Angiolo Mazzoni were some of the makers of the infrastructure of the country between the two World Wars. Post-offices, railway stations, and municipal buildings were some of the building types receiving design attention to realign the built environment to European standards, on one side, and to the nostalgia for Imperialist Rome, on the other.

With Post-War reconstruction, the climate became radically different. A more populist angle than the earlier period and an embrace of left wing principles—with occasional folk overtones—permeated the built portfolios of architects, who felt unprecedented societal responsibilities for their work. A renewed focus on the living conditions of the working class, particularly in the 1960s and ‘70s, produced countless affordable housing projects tailored to address the needs of those who had limited participation in the benefits of national wealth. Strategies of participation, developed to involve end users in the design process, became mainstream practices in the professional routine of politically aware architects. With significant differences, the early work of Giancarlo De Carlo, Renzo Piano, Carlo Aymonino, and Aldo Rossi is situated in a philosophical perspective imbued with empathy for socially vulnerable groups.

Broadly speaking, the contemporary role of the Italian architect is molded on the split between the memory of a by-gone cachet and their current actual influence in public policy decision-making. Such a predicament can be partially attributed to the post-war rise of a technocratic strand led by engineers, trained to take over the technical expertise on building matters. From a legal standpoint, a licensed architect and a licensed engineer can perform exactly the same job. Engineers can sign off on architectural design, and architects can stamp structural drawings. This is not unproblematic, due also to the continuous surplus of architecture graduates and the even more numerous engineering graduates. As architects are unable to benefit from the protection of the law for their distinguished monopoly of competence and professional distinction, they have to contend with the uncertainties of an unregulated market.

When it comes to taste, architects maintain a leading voice in the public forum. Contention over courses of action are particularly frequent when interventions are located in the historic fabric of the city. The old centers of Rome, Florence, Venice, Bologna, are considered city museums occupying monumental roles in the architectural identity of Italy. Each region of Italy carries unique architectural traditions that frame the conception and collective absorption of an architectural artifact. Architecture as modification of existing structures is a disciplinary specialty that has emerged since the late ’70s. Ever since, preservation is preferred to new intervention when both options are feasible. And architects do lead the process of urban modification as sensible experts on the aesthetic demands of the built environment.

The size of architectural firms is primarily geared toward the domestic market. An office staffed with 80 employees is rare in Italy and likely to be found in either Rome or Milan. If it is true that Renzo Piano is Italian, it is also true that his practice is a national exception shaped around Anglo- American models of organizational efficiency. More common are small and medium firms who often undertake infill projects in a rather dense urban tissue.

Being an architect in Italy is synonymous with being an intellectual. Sooner or later, architects with a public presence engage in literary self-reflection about the conditions of practice and broader questions of public interest. Often, writing is related to obligations in academia, but not exclusively. Renzo Piano’s Dialoghi di Cantiere is a classic example of autobiographical accounts of architectural projects as personal adventures. In addition, as intellectuals, architects regularly get involved in the political life of their community, either as informed voices dealing with the local authorities or directly assuming political office.

JAPAN

Hajime Yatsuka worked for Arata Isozaki from 1978 to 1983 and established his own office in Tokyo in 1984. His work has been widely published; projects most familiar to overseas readers include “Tarrlazzi” (1987), “Athene Multimedia Center” (1997), and “Nagaoka Folly” (1998). Author of numerous books, he is an editor for the journal Ten Plus One and a regular contributor to Shikenchiku (Japan Architect). Mr. Yatsuka served as deputy commissioner for the Kumamoto Artpolis from 1988 through 1998, assisting the prefecture to select non-Japanese architects for projects and coordinating interactions between overseas designers and local architects.

Let me begin with an old memory from the early ’80s, when I had been working on the design of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles for Arata Isozaki. The L.A. Times came to the office of Gruen Associates (our local architect); they wanted to make a report on the work-in-progress. Unfortunately, Isozaki was not there. They asked me to stand by the model, together with the president of Gruen Associates, for the publicity photos. Obviously, they wanted to show some Japanese guy working on the project. I was impressed, because that was quite unlikely to happen in Japan, as architects were not popular figures in the mass media yet (with a few exceptions, such as Kisho Kurokawa, who married a popular actress, and Kenzo Tange, who was a national hero).

Some twenty years later, this week, I saw a train-car advertisement for a popular journal offering fashionable information for urbane people in Japan. These advertisements provide us what Route 66 in Las Vegas perhaps offered the Venturis more than thirty years ago. On the advertising poster was a large image of Rem Koolhaas. This was for an issue on what is now happening in Beijing; the flying Dutch architect, who was mentioned as a “charismatic figure of the contemporary architectural scene,” was taking photos (of course with a small digital camera) of the central plaza in Beijing, a place where students were killed more than a decade ago. Koolhaas is now involved in a huge project there. The model photo looks very exciting and very capitalistic!

This is the reality (anti-reality?) of how architects are perceived in Japan. They might be a hero at some moment, some place, on some occasion; but likely not for people in the provinces, where there is no dense network of railways(!), and they are mostly overlooked by the mass media, as if they are non-existent. (Western readers might have no image of the Japanese countryside. Japan is not formed only by several metropolises; more than 60% of the Japanese population are still living in rural areas.)

Another popular figure, Tadao Ando, with whom I share a client (and honestly speaking, who was even kind enough to introduce me to them) once told me an extremely illuminating episode. A potential client came to him and, after asking his opinion on the project, put the final question, “You don’t seriously need a fee for the design, do you?” Architects, if as well known as Ando, are influential persons worth being associated with, but scarcely treated as professionals with skill and responsibility, of which these people have no idea — “OK, Mr. Ando, it is our honor to have your sketches or whatever, but our contractor could produce drawings. You didn’t spend too much time on the sketches, which is why we actually do not understand what is the nature of the fee for architects….“ That kind of reaction is still, even today, likely, even if many clients are not rude enough to give it voice.

There used to be a rumor (before the 1980s) that a respected intellectual magazine made it a rule to feature an attack on architects when they found no better subject to deal with — although there were hardly a sufficient number of publicly known architects at that time to become targets. I do not know if this rumor held any truth or not, but it is perhaps illustrative that many of us referred grimly to it. But one memory of a piece as it was actually published was quite clear: a well known modernist (and leftist) literature critic blamed Kenzo Tange because the knob of one of the doors of a recently completed building of his design was too easily broken, insisting this was caused because his design neglected practicality and thus showed the architect’s social irresponsibility! It goes without saying that this door was for some insignificant room and not designed in a singular way. This episode illuminates the idea of the architect’s social responsibility held by the left wing intellectuals. It is rather an old story, but one that could happen today.

The situation has both changed and remained unchanged. The Ando episode is based on the Japanese building tradition in which the aristocratic client, when sophisticated enough, made a decision on the design and the builder provided technical skill and labor on the site. This tradition survives in the contemporary custom in which general contractors produce shop drawings and, consequently, legally share the responsibility for the completed buildings with architects. If they do, what is the architect’s role? But on the days in which architects were hardly media darlings and there were a more limited number of jobs, there was some appreciation by our clients for the work of architects. People had the choice of using the contractors’ designs and did not have any other reason to give a commission to the architects than an appreciation for their work. As a selected few architects became celebrities, expectations have changed. I have elsewhere written on the Expo ‘70 in Osaka, the event that was an ambitious experiment by architects led by Tange. But the experiment succeeded only as a popular, mass culture event, to their bitter disappointment. This moment marked the shift from modernism to postmodernism in architecture in Japan, in which the media (e.g., advertisement agencies) took command. After thirty years, architects themselves are becoming the object of advertisement, media heroes.

Quite recently, I attended a lecture by an architect from the US, speaking in Europe. To my surprise, he showed two Japanese projects. I was surprised, because I knew both projects (but not his design). One was an open competition. I also participated; both of us failed. So viewing his scheme was no surprise. But the second one was a large complex of research and other facilities. The project—and I am not sure if it was finally built or not—was never made freely open to architects’ proposals, as far as I know. By coincidence, I myself was also consulted about the possibility of being involved in it. Apparently, this architect was commissioned after I quit the project. I left it without producing any scheme at all, because I realized one of the agencies involved had no intention of building my proposal, regardless of its content. They simply wanted publicity images for raising interest (and funds) from other investors. The actual design would be done by some large commercial firm (or contractors), with no ambition in terms of design. I do not know if my American colleague was informed of this or not, while working on the project. If not, that is our shame apparently; I was not either, but I simply had the advantage of realizing this background. I am sure he got paid, but he was paid for a marketing image, not for the substance nor the responsibility that accompanies an architect’s design. Maybe our situation is not so different from the US, in reality. It is rather natural in the age of globalism.

Forgive me for only juxtaposing these examples. Your question—if architects are admired in my country—is too difficult to answer in a definitive way. So I only hope you might draw your own conclusions.

MALAYSIA

Laurence Loh is principal of a twenty-person private practice in Penang, Malaysia. His earlier working experience included work with a 150-person practice with three offices, as well as with the Penang Island local authority, architectural department. He apologizes for suggesting, by constant use of the world “he,” that the architectural profession is a male domain. There is no gender prejudice intended, but what is the reality?

When a graduate starts his working career in a Malaysian practice, he quickly discovers that the profession is regulated by law. (Terrorists take note. Don’t come to Malaysia disguised as an architect.) In 1967, the Architects Act was promulgated by Parliament, and this single piece of legislation starts to shape the aspiring architect’s career. So a fresh graduate’s short-term mission would be to obtain a license to practice, to be sanctified to put his d h o b y mark on plans to be submitted to the regulating authority for approval.

In order to get there, he must first register as an “architectural graduate” with the government’s Board of Architects. But this can happen only after he pays his dues to the Pertubuhan Akitek Malaysia (PAM) or the Malaysian Institute of Architects as a “graduate member.“ Why? Because the law says so. Without being a member of the Institute, you cannot be registered. Then he religiously maintains a logbook for two years and sits for an exam prepared by PAM after prior screening of his logbook. If he passes, he can then apply for his license. This process generally takes three to five years.

After thirty years of practice, I know of only two successful Malaysian architects who have gained public prominence and the respect of the profession (albeit given very grudgingly), despite their non-conformance with the system. Both are graduates of the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London, and both have chosen not to take the conventional route for one reason or another. A coincidence? Recently, I interviewed both of them.

A contentious interpretation of the law was the initial catalyst for their rejecting the registration route. The law specified that, prior to sitting for the professional practice exam, the aspirant had to accumulate two years of working experience from the date he registered with the board as an “architectural graduate.“ Both had worked for several years in prominent British practices (Foster, Rogers, Grimshaw). One had even been registered with the Architects Registration Board of England. Many returnees had been caught unaware by a narrow interpretation of the registration requirements. Having failed to register immediately on completion of their respective courses, most served extra time to meet the requirement’s interpretation. These two architects, however, chose not to and stayed out of the “unfair“ system.

Both interviewees confirmed that, although there were initial disadvantages, the AA spirit prevailed. “The AA taught me to be street smart,“ said one. With partners who are registered, his firm has grown to become one of the most sought-after practices in Malaysia. To this day he maintains it is the “AA survival kit“ that kept him going.

The second architect I spoke to said, “The AA doesn’t brand you. You learn how to be flexible, inventive, with an edge on perception.“ He found that the design of individual houses (“doing the smaller projects“) became the ground for “experimentation through implementation, backed by a strong theoretical base,“ which he then articulated in international forums and competitions. This process has kept the edges sharp in his approach to new-built work. These architects have my admiration.

Talking about admiration and the public’s view of architects, I would say that the Malaysian press, which creates the myths, does not see architects as popular heroes. And if what is given credence and space in the local news is a reflection of interest, attention, and taste, then I would profile a newsworthy architect as one who owns a publicly listed company, appears in the Business Top 100 chart, is quoted in the business section of the dailies, is seen in public with the prime minister, drives the latest Mercedes Benz or BMW (the higher number series), and has aspirations of being a politician. (He would have registered himself with the appropriate political party on the same day he got his badge to practice.) I can think of two architects who are ministers in the national cabinet at the moment.

Notwithstanding the above, most architects, especially those who do not have an entrée into the privileged class, get on with their modest lives. Technically, they work with what is being promoted by the building industry, exemplified by what is displayed, year in, year out, at the local international building materials trade fairs. They eagerly await the arrival each month of the foreign architectural magazines they have subscribed to and check them out for new ideas, especially whatever is being promoted as flavor of the month. Arbiters of taste? Whose taste? Does Shanghai’s skyline look different from Kuala Lumpur’s or Singapore’s? Architects are mainly followers.

In the Malaysian architectural profession, architects work with laws based on British models. For example, the Town and Country Planning Act and the Code of Ethics in the Architects Act impose traditional contracts and tendering systems introduced by RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) expatriates. The architect is the supremo in a system that would have worked when it was a gentleman’s profession, but now every institutionalized discipline, especially project managers and planners, wants to wear the pants in Malaysia.

But wait! WTO and changes are around the corner. Two-thirds of the Malaysian architectural profession, trained in Britain and Australia, do not have a clue about American systems of procurement and marketing. So heaven help them, if China’s condition is anything to go by. Get ready to welcome free enterprise, no-obligation proposals, no fixed scale of fees, aggressive marketing. The only consolation is that the word “Architect“ is still a legal entity, and the term can only be used by persons registered with the Board of Architects as such beings. Having said this, nobody to date has been prosecuted for calling himself an architect when he has not registered as one.

SOUTH AFRICA

Leslie Mukwakwame Musikavanhu is managing partner of Cre8 Design & Innovation, a six-person firm in Johannesburg, South Africa.

A new revolution simmers across the African Plains. It entails that we take time to look back to our past—sometimes it is there that we will find the answers. In a trying time like this in Southern Africa, it is difficult to fully address any topic without bringing in politics. The issues of land have brought about selective amnesia and interpretive disagreement among the peoples of Southern Africa. The question is about how far we go back in time to correct the errors and omissions of the present.

The sankofa bird (of recent past West African teachings) is a bird that flies forward and constantly looks back to its past. It is my humble opinion that, in trying to design spaces that are purely African, one has to look back at how and why it was done back then.

The revolution is eternal

The revolution is internal.

It is also paternal and maternal,

All in the same breath.

All in the same death.

The revolution knows –

No Death;

The revolution enjoys more breath.

The revolution deploys more berth.

The revolution implores more birth.

I greet you with all the titles and totems to which you are rightfully born.

My love affair with Architecture is one that stretches far beyond the reaches of this lifetime. Rooted in allegory and meaning— the architecture of our forebears has quickly lost its ground.

I have been fortunate, since my return, a little over three years ago, to have worked in a number of Southern African countries at the same time. A great number of them are seemingly locked in a time warp—a mere shadow of the happenings of a time gone but not forgotten. The paint peels off the walls, as if the pain has taken its toll on the buildings as well. It is history locked in structure—it is honest about its time.

A strong cultural upbringing and “The Tuskegee Experience“ have gone a long way towards readying me for the many challenges of being a young, black architect in Southern Africa. It is going to take a while for the prejudices to be eradicated, if that is at all possible. It is out of the desire to have power and control that we develop the habit of prejudice. We still need to find ways to even the playing field properly. Sometimes the act of doing so comes at too high a cost. It is, however, an exciting time for architects practicing in the region. I say exciting because of the boundless opportunities to influence the way space is perceived for generations to come.

Historically, African architecture has primarily been about mediating between defense and culture. Defense in its broadest definition possible, from the elements and would-be invaders. If ever there is a more fitting essay of the history of the people than that of the architecture of Africa, I surely hope to experience it someday. Some of the purest structures I have ever had the pleasure to experience are also the simplest. Examples are the ancient ruins scattered throughout this region.

Architecture in present day Southern Africa is caught between the most glaring and amusing clichés and the most intoxicating expressions of cultural inflection. There are those who feel that African architecture is about the random appliqué of traditional features and motifs. Then there are those who religiously mimic the trends and designs of the West. In our recent past, it has been about how one mediates among all affected parties within the context of the site—inside and out. It is no surprise that the architects of yesteryear were also the mediators (vessels for translation).

TURKEY

A. Ipek Tureli is a Turkish architect trained at the Istanbul Technical University and at the Architectural Association in London. She has taught at the Middle East Technical University and has worked in firms in the UK and in Turkey, most recently the fifteen-person practice of Arthur Collin Architect in London. She has collaborated on voluntary community projects in Anatolian villages while pursuing a PhD at METU in Ankara. Currently she is continuing her doctoral studies in architectural history at UC Berkeley.

If one were to make a survey on the street, asking passersby to name a Turkish architect, the reply would be, “Mimar Sinan,“ the Ottoman architect of the 16th century. Nobody would be able to cite any contemporary architect. In Turkey, architecture is not part of popular culture; construction, however, is. This state of affairs is not due solely to economic unviability or public lack of interest, but also to the self-organization of the profession.

In the Ottoman Empire, architects functioned as bureaucrats; they did not have a social standing as “artists.“ The academic education of the discipline of architecture was initiated in 1847 within the Royal School of Military Engineering. The first law defining the practice was issued in 1927. The law regarding the Chamber of Turkish Architects was issued as late as 1954. The number of schools of architecture was three in 1960, thirteen in 1990 and thirty-two in 2000. In the 1970s, the duration of education was reduced to four years, and constraints regarding practical training were loosened.

A striking aspect of the current Turkish education system is that, since the early 1980s, the Turkish Institute of Higher Education (YOK) has governed all universities and university entrance examinations. Hence, schools of architecture are not independent in administration, and they cannot choose their own students. The students are blindly placed according to the points they earn and the preference lists they have submitted. In these listings, architecture, along with medical studies and law, has been consistently in the upper middle range. Architecture is respectable, but not that popular, since it will not bring a lot of income.

The number of architects in Turkey was only a couple of hundred in the 1930s and around three thousand at the beginning of the 1960s, according to the Chamber of Turkish Architects. As of February 2003, there are 29,164 architects in Turkey, proliferating each year, and the market demand is simply not enough. From an elite, well-respected profession throughout the early Republican period, architecture has swiftly turned into a technocratic one whose main duty is providing service. Starting in the 1960s, building became a type of investment for the middle classes. Moreover, in the early 1980s, with economic liberalization, big capital started systematically investing in the construction industry. Many development companies, which are both the client and the contractor, emerged. Small-scale commissions became almost obsolete. Refurbishments and interior decorations constituted the majority of the jobs for practicing architects. (Here, I am recording a general opinion and not an empirical finding. To my knowledge, there have not been nationwide surveys conducted on what kind of work architects are doing, how they are practicing, or if they are practicing.)

The number of non-academic architectural journals rose from three to a dozen, all of which publish relatively little of Turkish architectural practice. Newspaper stalls are filled with an ever-increasing number of “interior architecture,“ decoration magazines. Many people do not know what an architect does and conflate it with the draftsperson. Today’s equivalence of the female to male ratio in the student body is not reflected in professional practice. Yet, among the wider public, architecture is increasingly seen as a “feminine“ profession, one that can be carried out from home.

Many practicing architects have been left out of the construction process and on-site project control. Architects frequently complain that the developers have altered their schemes. The legal architectural project becomes a hindrance to acquire the approval of the local authorities. Once the construction starts on site, there are not any strong mechanisms of official control to assure the one-to-one realization of the architectural project. Because of the disastrous 1999 earthquake, people have become more conscious of where they live, but market forces dominate and even capitalize on the fear by promoting suburban developments.

In summary, market forces have re-defined the profession in a way that does not exactly match its Western counterpart. This divergence creates a big dilemma within the profession, which itself is a Western invention. In addition, its education is a Western, specifically central European concept. In schools of architecture, the curriculum privileges Western design. For example, as Gulsum Baydar writes in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (March 2003), in architectural history survey courses, “the priority of Western architecture over native histories remains unquestioned.“ Although with some delay, almost all the style-isms and trends are experienced deeply. Architectural practices generally operate in an amateur fashion; they do not archive their work or promote themselves in architectural journals, because commissions are acquired by personal references and not design/brand promotion. What is also interesting is that, given the large number of architects, there is little intellectual production among architects on architecture and little professional support from fellow architects or the Chamber of Turkish Architects. Finally, the pro-Western elitism of academia persists to the level of denying the “architect-ness“ of the very architects they have produced, because, alas, once in the market, they do not conform to the ideal of the “designer“ architect.

Despite these impediments, Turkish architects are excited about the possibilities of global practice. International and national recognition in the past two decades have fostered this view. The Aga Khan Architecture Awards (1977-) have played a special role in the reception of Turkish architecture, both abroad and in Turkey, by awarding seminal figures such as Sedad Hakki Eldem, Turgut Cansever, and Behruz Cinici. International architectural journals like Space Design ( 1 9 9 3 ) and Architecture & Urbanism (2000) have opened up space for a younger generation of architects, such as Arda Inceoglu, Deniz Arslan, Nevzat Sayin, and others. XXI Architecture Culture Center of Turkey has promoted young architects by organizing the “Quest For New Approaches in Architecture: Young Turkish Architects“ traveling exhibition in 2000. Among the participants were Han Tumertekin, Can Cinici, Gokhan Avcioglu, Teget Mimarlik, Emre Arolat, and Semra Teber.

VENEZUELA

Enrique Larrañaga is partner of Larrañaga-Obadía, Arquitectos Asociados C.A., a six-person firm in Caracas, Venezuela. He teaches at Universidad Simón Bolivar, where he was previously Coordinator de Arquitectura.

My Turn to Complain

Whenever I have ventured to compare my architectural practice in Venezuela with that of friends all around the world, I have come to the same conclusion: whoever speaks, wherever he or she has practiced, always endures the least respect, the lowest fees, the worst working conditions, and the most absurd regulations. This may mean that architectural practice is not all that different, however different cultural, economic, climatic, and technical contexts might be, and/or that architects, everywhere, think of themselves as more dedicated, valuable, relevant, and groundbreaking than what common people believe. If you think that no one suffers architecture more than you and are not willing to accept otherwise, stop reading, because I am going to present my case and, following the above described silent pact, demonstrate the difficulties of architectural practice in a developing country.

Let me start by raising the envy of American readers: architects in Venezuela are seldom liable for what they do, and no malpractice suits have been known. Then—and going back to my right to complain—not being liable also implies not being reliable; at no legal risk, details, specifications, and even shapes and measures stated in drawings and documents become just generic indications of how things might look. With architecture schools only some fifty years old and derived from engineering schools, architects are mostly seen as estranged sons of a respectable profession with nicer taste, who tend to make things prettier but also more expensive. Their opinions should always be distrusted and often ignored. This situation, of course, grants great professional alibis, for you can always claim the contractor changed whatever looks awful or argue that anyone, but you, made the wrong decisions. And this might even be not untrue.

No one seems to care much about this lack of respect. Professional organizations are weak, to say the least, and their legality is only relative (“Colegio de Arquitectos“ is just an association within “Colegio de Ingenieros,“ the only organization you need to belong to in order to practice). Adding to the obvious implications of this pariah condition on the questionable value of what architects do, no official honoraria parameter has been set, and deciding on that is one of the most exhausting parts of any job. Having been as afraid of losing the project for going too high as of leaving money on the table, when you believe you have made up your mind, some just-out-of-school nephew working in mom’s garage might pop out and take away the opportunity for half the price. In Venezuela (advantage, aberration, or just a condition?) your diploma is your license, and no registration exam is required to keep it valid.

But sometimes you do get work. Lucky? With inflation rates of “two low to mid digits,“ even the best fees evaporate in a short period of time (something you, your employees, and your consultants notice promptly but your client pretends never fully to understand). Hard as it is to work on a project when no projections are possible and “inflation clauses“ are unfeasible, you just hope the uncertainties brought by inflation won’t deflate your client’s will (and account) while your time, payroll, and patience all keep going on and running empty.

Crisis has taught Venezuelan architects to survive and develop creative abilities. One of them is the skill to draw a project that will comply with regulations to pass official review but can later be changed without permit to answer actual requirements. Loose controls and ample irregularities make this possible, although at some cost, which the client will gladly assume as a sign of both power and shrewdness. And as a sign that you, the architect, did what he wanted and not what you pretended, as it should be.

By now, you must agree that my practice is worse, harder, and braver than any; or wait for your turn.

However, the hell I have described is also the one I know and the one I (please do not repeat this) enjoy. We architects exercise optimism to naïve heights and pretend a not less naïve transcendence, as Quixotes fighting against code windmills with CAD spears. Perhaps that is our essential tragedy: thinking that this outstanding thing we do and nobody cares about is the best and the worst possible life anyone could choose, having done so some years ago and insisting on it every morning, while putting on the armor. Another professional commonality that comes with the black T-shirt.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2003, in arcCA 03.2, “Global Practice.”