photo by Susie Coliver.

Design can strengthen interaction within a community and promote social sustainability. The siting and design of housing are integral to the vitality of our social fabric and can make a positive impact on the social sustainability of the urban environment. In a recent discussion with Sam Davis, FAIA, Professor Emeritus of Architecture at U.C. Berkeley and author of The Form of Housing, The Architecture of Affordable Housing, and Designing for the Homeless: Architecture that Works, Davis described the relationship between housing and social sustainability:

“Social sustainability is an area unto itself, and it’s not mutually exclusive from environmental sustainability. If your intention is to nurture a planet on which people live comfortably, then that means everybody—you can’t leave somebody out. That’s the underpinning of all sustainability. Social sustainability is characterized by healthy, vibrant communities. They’re not polluted, the infrastructure is modern, and we don’t have gaping holes or blight. It’s an all-encompassing, healthy city. If you have people who are left out, you’re not fulfilling the mission. A consideration in this is that, when people leave a city because it’s unpleasant or not filling their needs, they leave behind those people who cannot afford to relocate. We no longer have a cross-section of people, a truly integrated, heterogeneous population that makes a place interesting. That’s where the housing part comes in—housing for different kinds of people with different kinds of lifestyle at different levels of income, at different points of their lives, with different physical and mental abilities.”

Three strategies for housing development have recently been implemented in the Bay Area, each with a different impact on social sustainability:

“Top-down” San Francisco

The Millennium Tower is designed to attract high-income residents, those with economic resources. The residents are attracted to amenities that the city offers, and their presence eventually supports jobs in the area. The tower is designed with support functions such as a fitness area, children’s playroom, and outdoor terrace, accessible to the occupants only, not the community at large. While it may be that, at this point in time, the building occupants are the primary community, with opportunities for interaction with the surrounding neighborhood only during the business day, nevertheless this is an exclusive, hermetic, vertically-oriented enclave, where community interaction may consist of little more than getting to know the few neighbors on your floor or in the fitness space. It is an example of “top-down” vitalization of an area, the fruits of which may materialize only over time. As long as the services are contained within the building, it is limited in its impact on the surrounding neighborhood.

“Uptown” Oakland

In the 1990s, then-mayor Jerry Brown vowed to bring 10,000 units of housing to downtown Oakland. A substantial number of units has been constructed, and the “uptown” area near the 19th Street BART station has become enlivened with conversions of existing buildings to living units. Along with new restaurants, the recently renovated Fox Theatre has become a venue for entertainment that appeals to a different demographic than that which frequents the Paramount Theatre a few blocks down the street. Not all the housing is “high-end,” yet there has been criticism that not enough of it is low-income. To Davis, “This is the beginning of a sustainable model: the type of housing that keeps people in town, supports local businesses, and is accessible to a broad range of people of various incomes.”

“Intergenerational” Palo Alto

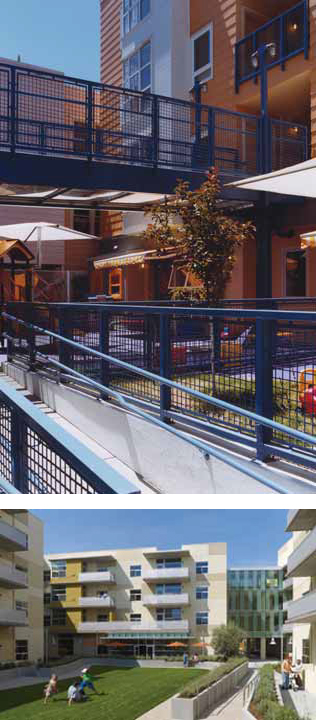

The Taube Koret Campus for Jewish Life, designed by Steinberg Architects, is located on an eight-acre brownfield site in the midst of an existing mixed residential and industrial area—a transition zone between Stanford University to the west and East Palo Alto. The project has 192 units of senior housing; in addition to continuum-of-care functions such as independent living, assisted living, and skilled nursing, there are fitness and cultural centers as well as an early childhood development center. The combination of programs on site supports an intergenerational community, whose members benefit from each others’ presence. The design of the outdoor campus itself promotes connectivity and interaction among the community. The City of Palo Alto has embraced this project as a catalyst for revitalization of the surrounding area.

Low-income housing: segregated or integrated?

“People choose, when they have the option, housing that fits their needs—whether there’s a school, or a church, or a job nearby. So, in a way, they’ve self-selected. But those with low income have limited options, and the homeless have even fewer. We have to provide them options in a reasonable way. Some people would like to see the homeless ‘out-of-sight, outof- mind,’ so sites like surplus military property such as Hamilton Air Force Base may be selected, effectively putting them in a remote part of town. Some people in the homeless service community think that’s a good thing—it gets them in a protected environment, they don’t have to deal with mean streets, they can be focused on getting the support services and employment and education they need. I don’t see it that way. I think re-integration into the community is the best approach. The problems with the non-integrated model are that there are typically fewer jobs outside the urban core, there’s limited or no transportation access, and there are no social services other than those provided within the development. I don’t think that’s a sustainable model.”

Integration includes programs that serve the community

“The homeless and very low income populations are themselves not heterogeneous. People are homeless for all kinds of reasons. Some have mental or physical disabilities, some just cannot make enough income. So, we need solutions that are as varied as the population and their needs. For example, homeless and low income parents, typically women, have specific needs: they may have a job, maybe they have more than one job, or they need to get to the job, they need a car or transportation. Where are their kids going to school? Where are the kids after school while the parent is still working? All these are needs that should be addressed.”

In Designing for the Homeless: Architecture that Works, Davis shows an example of the Canon Barcus Community House in San Francisco, designed by Herman Coliver Locus Architecture. Of it, he says,

“There are many communities in that building. There’s a play area and daycare, so that when the kids come home from school they go to the daycare on that site, so the parents have some level of confidence, some peace of mind, that the kids are near the home. That’s a perfect example. Another one is that the social services for the homeless families that live there have an entrance through the building, and there is also an entrance from the street. Here’s a way to connect the people that aren’t living there with the needs of others in the community that may overlap. To me, that’s what really helps knit the community together. The architectural aspect of that is that the social services are at street-level, similar to commercial space, a ground floor use that has some visibility and interaction during the day, that’s not a blank wall, that fits in with the city.”

Integration and vibrancy

Housing can be designed to foster and nurture our social interactions with each other. In these interactions, we may learn to appreciate the diversity of our community. The value of design is to build on the foundations of civility. Davis observes,

“It’s tough. I’ve been around the homeless a lot, so I know it can be very intimidating, very tough, which is why I think we need to get them off the street into good housing. But there are still going to be people of low income around, and for the most part good cities are like that. The ‘membrane’ of civility is incredibly delicate, and it does not take much to pierce it, whether it’s road rage or intolerance of someone who does not resemble you. I think we need to do the kinds of low-income housing that Herman & Coliver, David Baker, and Leddy Maytum Stacy are starting to do in San Francisco. Unfortunately, it’s just a drop in the bucket, yet it is needed in addition to the ‘vertical neighborhoods,’ in order to diversify the community. Good housing is critical to social sustainability, which supports a vibrant community with a broad range of demographic and economic strata.”

Author Grace S. Kang, SE, LEED AP, is a structural engineering principal at Forell/Elsesser Engineers, Inc., a San Francisco-based structural engineering firm focused on improving the safety and sustainability of the built environment. She is a professional affiliate member of AIA.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2010 in arcCA 10.2, “The Future of CA.”