Any architect who has the opportunity of working on an older building usually asks if any original drawings exist. Sometimes the answer is “yes,” and we are brought face to face with the history of our profession. For me, the older building was the Mark Hopkins Hotel shortly after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. With little flourish, I was handed a modest-sized roll of original, ink-on-linen tracings comprising the complete architectural, structural, and mechanical plans for this 1926 Weeks & Day landmark building.

Aside from my first impression of how beautifully crafted the tracings were, what surprised me most about the plans was how integrated the information was. My immediate feeling was that a builder could construct (and probably did) the entire building from just that drawn on the architectural sheets. Structural and mechanical information were both shown on architectural plans, in contrast with current construction documentation canon.

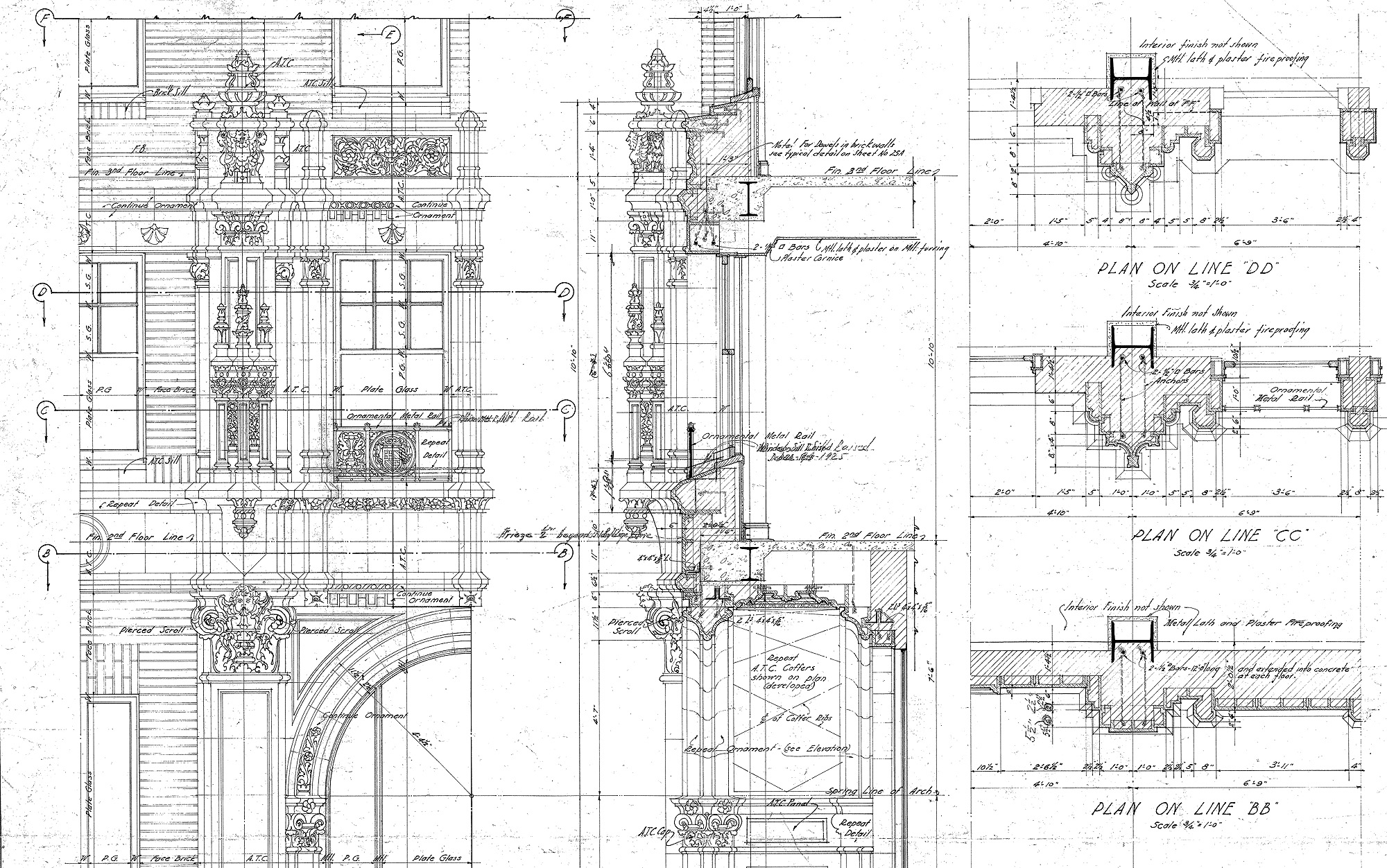

Seemingly missing, however, were sheets of details. While some beautifully drawn details were present in the set, where were the hundreds of drawings needed to show elaborate terra cotta ornamentation, intricate masonry construction, iron work on the canopies, sheet metal cornices, to say nothing of the interiors? How could so complex and ornamented a building be constructed with just these scant, albeit beautifully rendered, plans, elevations, and few, small-scale sections? Clearly the building had been constructed, and looking exactly like the 1/8″ = 1′-0″ elevations, but without the balance of information necessary for all the trades to perform their work.

In the weeks that followed, as I studied the documents further, I became aware of how much material knowledge was imbedded within the architectural drawings. Every convolution of architectural terra cotta demonstrated not only ornamentation but also a thorough understanding of how material was formed, fabricated, and secured to the building. Comparatively few notes appeared on the tracings, but knowledge of materials and assembly were clearly present and crafted into beautiful drawings. It was as though the artistry of the construction drawing equaled the craft of the trade constructing the building. And that was enough.

How different is our profession today? Architects design beautiful and complex buildings, but how do we indicate knowledge of materials and assemblies in our designs? Moreover, is it ultimately important that we clearly demonstrate a knowledge of building, or is it better if the architect leaves the building to the builder and concentrates instead on form, idiosyncrasies of program, coordination with consultant disciplines, and countless lifesafety provisions that every design must integrate? Or, how many of us believe that project specifications can and do carry the balance of information not shown in our drawings?

Some of you are probably already nodding your heads in agreement or girding yourself for battle after such an audacious set of questions. Nevertheless, this very subject is being actively debated within our profession and affects how we perform our work and our role in the building process.

The profession of architecture has changed since the building of the Mark Hopkins Hotel. Construction documents are not the same device now that they were in 1926. Today’s construction documents serve many roles: They must give the contractor what he needs to understand design intent and construct the building; they must also clearly define information that regulatory agencies need to understand in order to review and permit the building. Construction documents are also key instruments of coordination with our numerous consultants; they serve as a road map for where information is found and how it integrates with the architecture of the building. And construction documents are a critical vehicle for constant pricing that takes place during the genesis of a project, culminating with a final bid, pricing that can and does determine the fate of our designs. Lastly, for those of us with a passion for how things are built, construction documents represent an apotheosis of design evolution, a point at which vision is meshed with knowledge, innovation, and artistry in order to bring ideas into reality.

Who among us have the fees for that? Better yet, for those grizzled veterans of construction administration, who among us have the fees not to do that? In this age of complex, highly integrated buildings, it’s no secret that architects are drawing more than ever. Projects I work on daily are multi-volume mammoths measured in thousands of sheets, with boxcars of specifications hitched to each drawing. Still, it is often not enough to build a building.

I return to the example of Weeks & Day and contrast those drawings with the knowledge invested into our documents today. Can each of us say that our drawings have imbedded within them knowledge of materials, assembly, and construction process like that of our predecessors? How many of us are using systems or products for the very first time? Have we been just a bit rushed to get the project out the door? In today’s environment of compressed schedules and reduced fees, how many of us look to construction documents as the most likely place to achieve schedule and fee savings? Can this phase be contracted out to a third party to complete? Can architects today relinquish direct authorship of construction documents and still maintain the control necessary to complete our designs? Or, do we instead follow conventional documentation practice, which states, “If you want it, draw it”? Should the architect who wants more draw more?

The Architect as Master Builder

Architecture is rooted in the concept of a “master builder”: an individual who is fluent enough in all building technologies not only to assemble materials as they are intended but also to combine them in new and different ways. This need to innovate is not just an expression of design in our age; it is also a response to budget pressures, codes, local building practices, and an avalanche of new materials, products, and systems. Each of us must, in turn, assess new products as any knowledgeable builder would: in light of construction methods, ease of assembly, warranty, exposure to liability, and complete fulfillment of our design. Any architect who holds himself distant from the master builder paradigm is delegating responsibility for his design decisions to another and runs considerable risk of losing design control altogether.

How then can today’s architects, with today’s fee structure, possibly function in this high-stakes model of construction documentation, where we must thoroughly document each material and building system extensively for fear of someone misunderstanding—wittingly or unwittingly—our design intent?

For years now, the answer seems to have been efficiency. Construction documents in the computer age have stressed standardization and the benefits of only having to draw something once and then make “minor” modifications. Others praise the efficiency of specifications that, in contrast to the adage of “a picture being worth a thousand words,” can describe a system and eliminate our need to draw multiple conditions. We talk of constructing “intelligent” models that can be sliced and diced at any scale, virtually eliminating specialized detailing. While all of these notions contain a promise of efficiency, they have not yet allowed us to substantially reduce our increasing load of documentation.

For my part, I believe an important concept of architecture is first to build our designs abstractly. Only when the architect can build his design in his mind and then on paper can someone even hope to build it with his or her hands. This process also connects the architect with traditions of building and the process of construction that is inextricably tied to how we work. This is the imbedded knowledge each of us must place in our construction documents in order that they fulfill their goal of transmitting a great complexity of information, as well as the careful study that each of us puts into our work. Successful communication of that knowledge to a skilled work force is the greatest challenge any of us will ever face. Designing increasingly complex buildings only intensifies that challenge. How, then, are we to work in a world that requires us to know more, say more, and draw more in order to see our designs complete?

The Architect as Master Collaborator

One future of construction documentation may be a process that teams builders and architects together early in the design process and charges them with successful completion of a project. Many of us are already using this model in one form or another. Known by many names, including “design assist” or “designled/ design-build,” I prefer to call it what it is: collaboration. Developers have successfully used this process for years, because they long ago realized that savings in time and efficiency of construction can easily outweigh savings achieved by competitive bids based upon enormous sets of plans and specifications.

In this process, the design vision of an architect is augmented by the specific construction expertise of builders who will construct the building. Architects benefit, because design ideas are quickly evaluated, and his or her efforts are focused upon refinement of design rather than inefficient excursions down paths of construction methods and materials that are not often the best way to accomplish design objectives. Builders benefit by taking on much less of the financial risk associated with “guessing” what it will take to build a design as well as covering commensurate risks of his subcontractors doing the same. Owners benefit by having real-time evaluation of project costs and much less exposure to cost overruns.

This is not a simple task, however, and, if anything, demands a more focused and greater knowledge of participants involved in this process. To be successful in this collaborative model, architects must not only bring design leadership to the table but also the qualities of successful construction documentation: namely experience, knowledge with systems being considered, and ability to rigorously research new materials.

Contractors, for their part, will more than likely be preparing shop drawings to a greater level of detail than they are used to submitting. In some cases, those shop drawings are incorporated directly into the construction documents and reviewed by building departments. The architect’s role in documentation will be to coordinate between subcontractors, much as he or she does with engineering consultants.

In an era of greater and more detailed documentation, this collaborative approach is a good way to leverage experience and knowledge at an early point in construction documentation. The architect, by conducting an open and informed dialogue with a builder and owner, has the ability to push design and innovation without unilaterally bearing the brunt of documenting and pricing that innovation.

As in the example of Weeks & Day in the early part of the twentieth century, it is clear that, when architects strive for innovation or even excellence in design, we must bring a great amount of knowledge to our drawings and specifications. While design doesn’t start with construction documents, it will be severely tested in this phase, and it is up to our profession to recognize the importance of construction documents and their role in the practice of architecture.

Author Brett Roberts is Director of Technical Design at Anshen+Allen.

Originally published 1st quarter 2006 in arcCA 06.1, “Imbedded Knowledge.”