“Our dangers, as it seems to me, are not from the outrageous but from the conforming; not from those who rarely and under the lurid glare of obloquy upset our moral complaisance, or shock us with unaccustomed conduct, but from those, the mass of us, who take their virtues and their tastes, like their shirts and their furniture, from the limited patterns which the market offers.”–Judge Learned Hand1

The popular residential landscape in any American suburb is a disturbing sight for most architects. Whether one sees “little boxes made of ticky-tacky,” environmentally unsustainable sprawl, or a world without architects, our professional values are offended. How did this happen? Popular American taste is the canonical explanation given for residential modernism being overtaken by the conservative postwar house and subdivision. Conservative taste en masse, this explanation goes, turned the postwar home into nothing more than a traditional cabinet for a wide collection of modern wonders, from dishwashers to TVs to air conditioners to wall-to-wall carpet.2 If we challenge this canon, however, we will see other reasons why the suburbs evolved basically without benefit of architects.

The idea of some homogeneous “popular American taste” in fact runs counter to the increasing heterogeneity of the postwar middle class, the clearly more progressive taste for other domestic products, and the logic of the media and postwar consumption, which suggests that desire is not only reflected in, but actually constructed by, the products themselves. Moreover, what evidence do we have that these postwar homebuyers had exercised their values or their taste preferences? It is hard to see that they had much choice, given the limited housing stock provided.

In the early stages of suburbanization, from the interwar years to the postwar period, architects designed prototypes that represented real options to the Levittown model that eventually overtook suburban development.3 From the twenties through the years immediately following the Second World War, architects were poised to produce a new residential landscape for America. It seemed certain that new technologies bred by the war effort, particularly prefabrication, would transform the housing industry and, with it, the form, program, and technology of the single-family house. “The Postwar House” became a synonym for the house of the future that would usher in more modern, more efficient, more spatially fluid architecture and the life-style to go with it.

The inevitability went beyond technology. Often called a “crisis,” emergency housing conditions since the Depression and throughout the war had fostered a willingness to experiment in various ways to produce homes. The hiatus in housing construction produced enormous pent-up demand. This lack of continuity and the surge in expected production were perfect conditions for a new direction set by new strategies in homebuilding. At the same time, the American family underwent change, with the increasing dominance of the nuclear family organized around childrearing as well as consumption in the privacy of its own home. Architects shifted their attention from custom homes for the wealthy to small houses for the emerging middle class, including all the men and women who would return from the war abroad or the war effort at home to live the American dream in the modern world.4

Numerous modern, model homes held unrealized promise, primarily because so few were actually built. Beginning in the late ’20s and early ’30s, we find the first examples of modern mass housing experiments. Buckminster Fuller’s 1928 Dymaxion House was a radical blend of industrial materials, prefabrication, flexible adaptation to individual site conditions, and existenz minimum, not to mention packaging and marketing. In spite of Fuller’s department store demonstrations of Dymaxion’s beauty, it was Wally Byam’s Airstream trailer eight years later that captured the popular imagination. Like a blend of the Dymaxion car and home, the Airstream Clipper made mobile living a recreational pastime. Its use of aircraft aesthetics and technology points to a terrain where “American taste” about forms of domestic life was less conventional than commonly assumed. From Wright’s Usonian House to Gropius and Wachsmann’s Package House to Breuer’s Exhibition House for MOMA, architects worked on new forms of domesticity that seemed immanent.

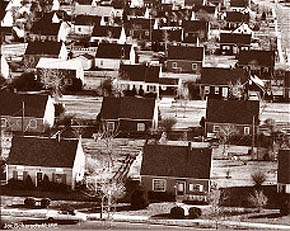

Yet builders across America rejected the architect’s vision of the postwar house, assembling their own models instead: Levittown and all its minor variants. A traditional if stripped-down house, complete with ridge roof and mullioned windows, was multiplied acre after acre. It was built by traditional construction methods, with little or no prefabrication. The builder’s house utilized principles of industrial production, not in the factory, as predicted, but in the field, with swarms of semi-specialized tradesmen moving lot by lot across immense sites. They built Cape Cod model homes by the hundreds, accompanied by the Ranch Style, each defined by a minimal amount of trim and minor reorganization of the façade.

Modernism took up residence within the house primarily in the kitchen and the bathroom, where hygiene and morality were embodied in a smooth, white, shiny iconography. Only a few modern spatial moves were made elsewhere in the house: the removal of the wall between the dining room and the kitchen, a related informality of program accomplished by moving the kitchen to the front of the house and the living room to the rear, the displacement and extension of the picture window to the private back yard as floor-to-ceiling glass or sliding glass doors, and the continuity between the interior and exterior ground plane achieved both by glazing and slab-on-grade foundations.

While not the first American middle class subdivision nor particularly inventive, Levittown can be taken as the benchmark of postwar mass housing. It is the primary exemplar of the genre. Except for the single amenity Levitt packaged with his houses each year, starting with a Bendix washer followed by a built-in TV, it is hard to imagine construction with greater economy. Economy is the obvious starting point for a critique of the popular taste explanation: the postwar family bought what it could afford, and this was the least expensive house on the market. But economy is not the full explanation.

From a review of the Case Study House program, archival records of housing architects, and the history of American public housing, it seems evident that modernism and the architects innovatively addressing the small house were offering a viable alternative. This impression, however, stands in direct contradiction to parallel research into government documents, homebuilders’ records, and interviews with homebuilders operating in the ’40s and ’50s. These sources offer, instead, rationales both political and pragmatic for resisting the modern house while propagating its traditional counterpart.

A number of factors pushed the postwar house toward standard building conventions and traditional formal manifestations, and these can be briefly summarized here. First, the two primary agencies regulating housing, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), instituted highly conservative practices in order to reduce the probability of another Depression. FHA guidelines insisted upon “no flat roofs,” and the HOLC issued instructions that modern homes were a lending risk.

Second, prefabrication did not easily dovetail with local building regulations that governed home construction region-by-region. Moreover, for various reasons, prefabricated housing—even that with government funding—was unable to deliver its product in a cost-effective or timely manner. One reason was that defense industries received priority for a wide range of building materials, yielding a shortage of steel and aluminum as well as wild price fluctuations when those materials did become available in limited supplies. Housing that relied on anything other than wood frame construction, including most experiments in prefabrication, was jeopardized.

Third, this pressure went hand-in-hand with standard home building practices. The interwar years had witnessed the emergence of a bona fide home building industry,5 which resisted change in labor practices or construction methods. There were few alternatives that could compete in terms of cost with the loosely detailed system of wood frame construction that depended on trim and plaster (and, later, stucco) to cover the consequences of speedy, moderately-skilled building.

Fourth, a most significant factor was the newly organized homebuilding industry, politically astute and knowledgeable about public relations. Its representatives lobbied successfully at local and national levels to resist changes that were not in their best interest.

Fifth, the postwar growth of the speculative real estate market lent strength to conservative building practices and to the creation nationwide of a relatively homogenous house marked by minor product differentiation. Lastly, in the anticommunist era of McCarthyism, modern aesthetics were dangerously associated with leftist, progressive politics.6 All together, these forces effectively restrained modern housing, limiting it to experiments rather than developments.

If, as I have tried to show, there was no shortage of design vision for the postwar house, and if a good many middle-class Americans held values that were consistent with more modern, more industrial, indeed more radical housing, then Levittown’s explanation lies elsewhere. The innovative, modern, postwar house was rejected not by the American public, but by other forces including the conservative regulatory and lending institutions governing housing. That conservatism was reinforced by the building industry, which was already established and clearly interested in maintaining the status quo. Finally, it must be said that we architects were not prepared as professionals to step into the political fray to argue effectively for our view of the future. The suburban canon was reified without that countervailing view.

Architecture for the popular American landscape is of course a matter of vision and careful design, as architects argued through their plans, but it is also entangled in webs of politics and prevailing practices. Our innovations depend not upon our designing houses and neighborhoods that fit into those patterns, but ones that recognize the real contexts within which change will take place.

1 Quoted in Bernard Rudofsky, Behind the Picture Window (New York: Oxford University Press, 1955), p. 201.

2 Thomas Hine, “The Search for the Postwar House” in Blueprints for Modern Living (Cambridge: MIT Press in association with the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 1989), pp. 167–182.

3 This article stems from research into residential modernism for my book, The Provisional City (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000), and from an architecture and urban design graduate seminar I taught in Spring, 2002, at the University of California, Los Angeles. My thanks to the students in that seminar for their thoughtful discussion and research into model homes and housing.

4 See Dolores Hayden, Redesigning the American Dream (New York: W.W. Norton, 1984).

5 Marc Weiss, The Rise of the Community Builders, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987).

6 Harold Zellman and Roger Friedland, “Broadacre in Brentwood?: the Politics of Architectural Aesthetics,” in C.G. Salas and M.S. Roth (eds.), Looking for Los Angeles (Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, 2001), pp. 167–210.

Author Dana Cuff is Professor and Vice Chair of the Department of Architecture and Urban Design at UCLA. She is principal of the consulting firm Community Design Associates of Santa Monica. She is the author of Architecture: The Story of a Practice (1992) and The Provisional City: Los Angeles Stories of Architecture and Urbanism (2001), both published by MIT Press.

Originally published 3rd quarter 2002, in arcCA 02.3, “Building Value.”