Operation BREAKTHROUGH was a program of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, authorized by the Housing Law of 1968. Under HUD Secretary George Romney, former chairman of American Motors Corporation, it combined a competition to identify promising approaches to industrialized building with a federal effort to aggregate a market for these new models of housing. arcCA spoke recently with Richard Bender, architect, planner, and author of A Crack in the Rear-View Mirror: a View of Industrialized Building (NY: Litton Educational Publishing, Inc., 1973); architect and urban planner Larry Dodge, and UC Berkeley associate professor Nicholas de Monchaux about Operation BREAKTHROUGH and its lessons for prefabricated building today.

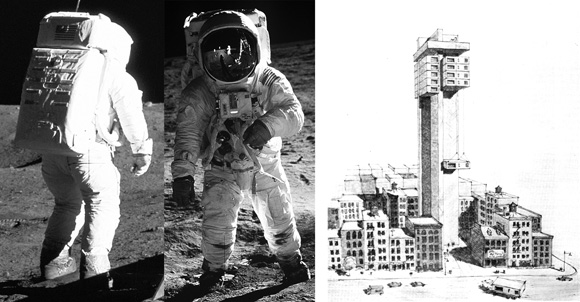

NdM: My interest in how prefab was being conceived in the ‘7os has to do with an investigation I’m doing, an architectural history of the Apollo XI spacesuit. Our enormous military industrial complex, with its vast expertise in systems and management, failed when it came to the task of making a spacesuit. Their hard, one-piece systems, which looked beautiful, failed, and the actual Apollo XI spacesuit was made by the Playtex bra company. It was a twenty-one layered, messy assemblage of different fabrics, only one of which was specifically designed to go into space. It was all adaptation and softness and messiness—the qualities that a lot of human landscapes have.

When I first got into the book, I thought there would be only a conceptual link to human landscapes, but it was interesting to discover that Bernard Schreiber—a developer of the ICBM—ended up founding Urban Systems Associates, a consulting firm for urban problems; or that Jay Forrester, who invented the Whirlwind computer at MIT, which ran a lot of the simulation systems used in the Cold War, wrote one of his last books on urban systems; that Harold B. Finger, who was an administrator at NASA, went to HUD, where he was a principal manager of Operation BREAKTHROUGH. And not only did he go to HUD but, by the time the Apollo program was winding down and NASA was downscaling, a lot of NASA’s state of the art physical technology was rolled down Constitution Avenue into Marcel Breuer’s HUD building, and people tried to figure out how to apply it to the problems of the city.

One of the more interesting parts of the current conversation about digital technology is the notion of parametric design, which can allow you, instead of designing objects, to design systems to design objects. So, based on local conditions on a facade, for instance, a louver can be milled in a particular way. And my limited research into Operation BREAKTHROUGH teaches me that none of these ideas are actually new.

RB: The title A Crack in the Rear-View Mirror came from the fact that a lot of what we’re speculating for the future is actually happening around us, and we don’t see it. For exam· pie, some of the companies that were submitting for Operation BREAKTHROUGH had been in existence during World War II. There had been a program then, preparing for after the war, in which the government solicited proposals for prefabricated housing. If you go back to early San Francisco, you’ll find prefabricated churches (shipped from Boston) during the Gold Rush.

Building Systems Development’s School Construction Systems Development project was a precedent for BREAKTHROUGH. There’s a picture in A Crack in the Rear-View Mirror of a helicopter putting an air-conditioning unit on the roof of the first test building, the first unit made to go on a roof. It came out of the building systems design process, and it revolutionized the way air-conditioning is done in industrial roofs. It was designed for schools as a way to be more flexible.

The idea was to get manufacturers to make things they wouldn’t make otherwise, by first aggregating enough schools with a similar need. A second idea was to make performance specifications for significant parts, like the air conditioning, and to tell people that if you can make a system that meets these specifications, there would be a big enough market to try it.

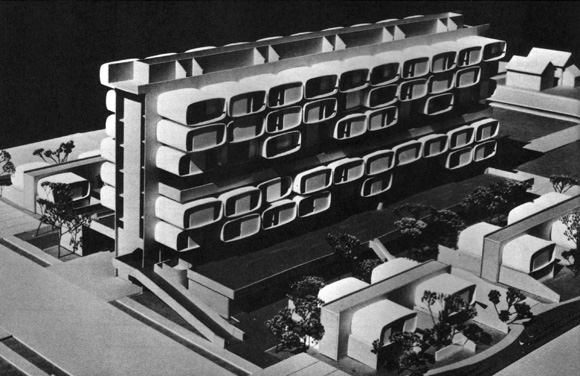

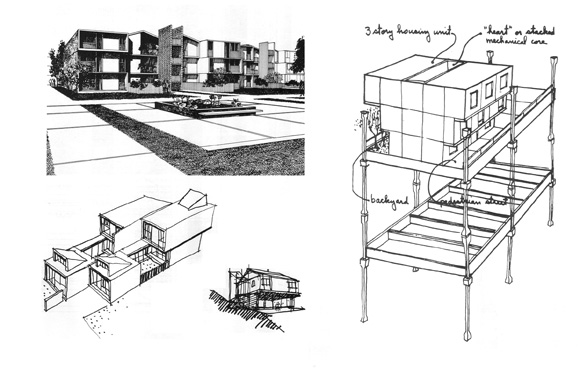

LD: BSD also did an industrialized housing project for HUD, which served as a model for BREAKTHROUGH, a bunch of small, scattered sites-1 can’t recall the number, maybe 2,000 units scattered throughout 200 sites in East St. Louis, Illinois. The response was not to make whole units but to be as efficient as we could in off-site fabrication that would still be responsive to particular site conditions. We tried to fabricate smaller scale elements of commonality off-site plumbing walls, for instance. There’s a tendency, however-whether to make more money, or to demonstrate a difference from somebody else for marketing purposes-to make things bigger and simpler for the producer. So even though I thought we had been too crude, when it got transferred to BREAKTHROUGH it was cruder yet.

Subsequently, we worked on one housing producer’s BREAKTHROUGH project that envisioned spinning Fiberglass housing modules in shapes with inherent strength. But the next step was: well, these are going to be for low-income folk, and the constraints were enormous. You couldn’t stigmatize the poor by doing some weird-shaped house.

RB: The best way to introduce innovation is from the top down. If you build prefabricated luxury houses, then eventually it becomes acceptable. If you introduce an innovation at the lowest economic level, there’s a feeling that you’re experimenting. And you are. The Katrina trailers are an example. They found out after families lived in them for a while that they poisoned people.

When you talk about the low end of the market, very often the advantage is not in the factory but in the way things are financed. As you put more into the module, you put more into the mortgage. When I was young, the refrigerator didn’t come with the house; if you go back further, the closets didn’t. We put more into the mortgage, and you finance the dishwasher and the refrigerator over a thirty-year period, and they don’t last more than five years. So you’re still paying for that first refrigerator. If you put less in the building and let people accumulate and finish it later, you may have a better strategy for making low-income housing than to try to build a finished house.

LD: Another problem was that the military thought in terms of a single housing market and one product. That wasn’t a response to the varied conditions of each project. It was too far away—a kind of space-view of the project.

NdM: That’s one of the points of my book. When it came to the individual bodies of the astronauts, one of the biggest battles that Playtex fought was to be able to size individual elements of the spacesuit to small, medium, and large for each astronaut. Even the slightest tailoring modification didn’t work in the institutional context.

RB: Boeing came to us at the time the supersonic jet was canceled. They had big layoffs, and they were trying to get into housing through BREAKTHROUGH. Boeing was fascinating: they were making the wings in Kansas and the body in Seattle, some of the engines were made by Rolls Royce, they all had to come together, and they were all working on them at the same time. That’s one of the keys with prefabrication, the idea that different people can make complex products in different ways but with the same interfaces.

NdM: A lot of this can be traced to the ICBM development. You bad an engine system and a fueling system and a gyroscope, systems so sophisticated that they needed to be developed separately. So systems engineers became interface designers, the new profession that came out of that process.

But even though the ICBM was complicated, it was in a way simple. This thing has to go up. it has to come down, it needs to hit the right spot and blow up. It’s rare that you get a problem that has a line drawn around it so clearly. One of the dangers in the systems approach, at least in the context of the military, was to say, “All these lessons we learned on this simple problem, we’re going to apply to things where the line is much harder to draw.”

LD: I feel I was a Neanderthal in a lot of ways, because I thought we were inventing rules, as though we can invent rules, or I know what’s best and it’s brand new. There’s something erroneous about the way industrial society has sliced up the world and then assembled new rules, whether it’s religion, or the Congress, or us inventing a new way of doing something, instead of seeing what happens and responding.

That there has to be a picture of the end product is the bane of every project. It could be because of financing, it could be land use organization, it could be somebody saying, “Well, we have to ensure a certain level of quality for the future.”

RB: A preoccupation of mine in this regard is evolution. The state of the art in evolutionary thinking focuses less on the traditional notion of evolution in search of optima, and instead on the idea of the best adjacent possibilities. That’s how systems change. A lot of what we’re talking about in the design of these systems is optima. Well, even if we identify what is optimal, we may not be able to get there from where we are. So we might look instead for possibilities that are better than where we are and adjacent to where we are, and we might look for systems to manage change.

Siegfried Giedion said that architecture begins with construction and ends with city planning. I started my career as a civil engineer. In New York, you could make a flat slab in an apartment house six inches thick and in a twenty-story apartment house get an extra floor. And you could just paint it. I realized architects were doing all the interesting work, so I went into architecture.

But one of the things you find out is, if you want to do low-income housing, you have to build a lot of houses. And when you’re talking about a lot of houses, you’ re going to need to become a planner, because everyone says, “That’s a good idea, but not here.” So my career moved from construction to planning before I realized it.

LD: If you look at things in a systems way, the end product is anywhere along the line. Everything is a component of some larger system. If you look at the world that way, then what’s the product? There isn’t any isolated product.

Originally published 4th quarter 2007 in arcCA 07.4, “preFABiana.”