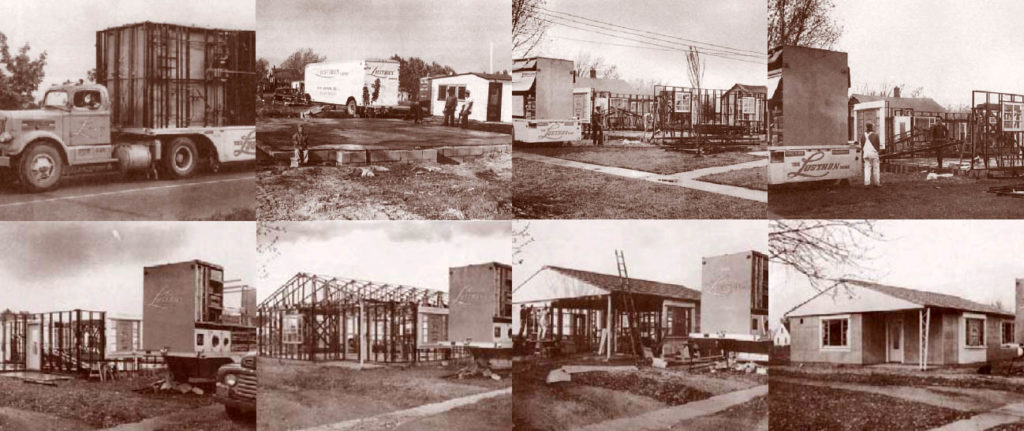

Lustron Home construction sequence, upper left photo, Clyde Foraker files/Dan Foraker Collection; remaining photos by Richard Graves.

In the quest for a definitive “modern” architecture, the notion of prefabrication has been a longstanding interest, if not a preoccupation, for architects. The term “prefabrication” has meant many things and been applied to a wide variety of building types, sometimes including the single-family residence. For the purposes of this discussion, one might nominally define prefabricated building as a factory production process that allows rapid site assembly of a permanent building to a fixed foundation, with little or no custom work. Generally, the objective of such building prefabrication is the creation of construction and assembly efficiencies with the implied benefit of increased affordability and/or profit. While prefabrication has been considered a kind of modern ideal in some quarters, one might also note that the single-family home’s highly personal and symbolic role suggests special challenges for those who would produce standardized buildings.

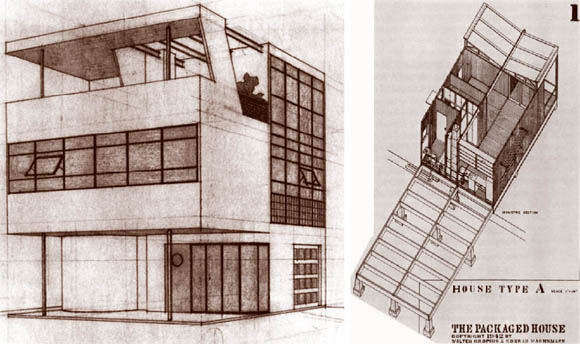

Architects have historically embraced the cause of residential prefabrication with vigor, designing a wide variety of futuristic “concept” homes intended for mass production. Among elite examples of this class are Buckminster Fuller’s “Dymaxion” house (1929–46), Albert Frey and Laurence Kocher’s “Aluminaire” house (1931), and Walter Gropius and Konrad Wachsmann’s package prototypes (1941–50).1 All reflect the conviction that “pure” prefabrication strategies can be fundamental to the production of single family housing, although none reached the mass-market in any significant quantities. Yet the ideal of prefabrication of single family homes—and modern architects’ longstanding affair with notions of building prefabrication— serve as a useful backdrop for an interesting and mostly forgotten example, the “Lustron Home” (1947–50). This brief but significant building experiment resulted in the construction of nearly 2500 units distributed throughout the Midwest and Eastern Seaboard.

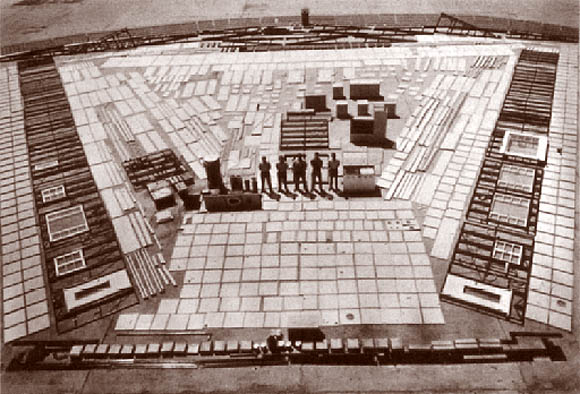

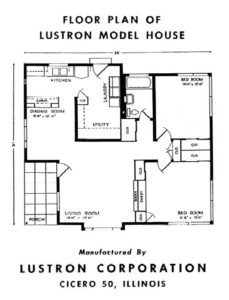

When compared to modern architecture’s most visionary projects, the modest Lustron Home was an unlikely protagonist in the century-spanning exploration of the idea of prefabrication. While the Lustron was indeed a concept home, it was also a cultural by-product of innocent, “Popular Mechanics” inspired notions of the future and the enthusiasm generated by wartime mass-production successes. Promotional literature promised low maintenance costs, since all interior and exterior surfaces—including the roof—were constructed of porcelain enamel panels. The original, 31’ x 35’ (990 sq. ft.) two bedroom house was priced at an affordable $7,000 and included built-in fixtures throughout. Among these fixtures were a combined clothes and dishwasher, lighting and bathroom fixtures, automatic water heater, exhaust fans, plumbing, electrical equipment, a 275 gallon water heater, and radiant ceiling heating.2 The steel in each unit weighed 12.5 tons, and the enamel weighed one ton. All 3,000 parts could be shipped from the factory in Columbus, Ohio, in a single 35 foot tandem trailer and be site-assembled in 350 hours. Land costs were not included, and local dealers were set up to assist with customer orders and lot selection.

The idea of living in an all-metal house was seemingly so unconventional as to reject traditional notions a family might associate with the idea of “home.” Yet the Lustron Home’s astonishingly widespread dispersion serves as evidence of its acceptance in the American heartland. By the end of the company’s short existence in May, 1950, it had constructed a total of 2489 houses, with a significant number of remaining back orders. While never reaching its break-even production rate of 35 houses per day, in July, 1949, it reached a peak production rate of 15 houses. Overly ambitious initial projections had indicated that the factory would produce at a rate of 400 houses per day. Projected site assembly times were similarly aggressive and were projected at 150 hours per unit, although typically under the best conditions the time usually amounted to 350 hours. When the company repeatedly failed to reach its predictions and required significant additional loans, bankruptcy followed.3

The hopes for the Lustron Home’s success were fueled by a postwar political climate in which mass production efforts of private companies had played an important part in helping to win the war; with such successes in mind, the U.S. government poured $37.5 million in loans into the Lustron Corporation. The company was the outgrowth of a Chicago parent firm whose decision to produce prefabricated houses was born out of a frustration with the lack of postwar steel for the company’s principal product—porcelain enamel metal panels for gas stations—and the government’s offer of support for firms that would address the serious shortage of housing for returning G.I.’s. Although it had not previously produced an all-metal single family home, the company was politically astute enough to exploit the government’s shifting priorities. While architects might think of Siegfried Giedeon’s mechanization polemics as the inspiration for such an ambitious prefabrication effort, the real impetus for the investment was the shortage of housing and the desire for new market opportunities in the existing metal panel industry. In retrospect, the significant losses that followed the failure of the Lustron Home left a peculiar and scandal-ridden legacy.

Despite this history, the Lustron offers an abundance of useful experience, including some important successes, regarding the opportunities and pitfalls of architectural prefabrication. First, and perhaps most prominent among the Lustron’s successes, was the surprising degree to which it reached its target market and captured the popular imagination. The most reasonable explanations for this aspect of its success were an aggressive marketing program (which included one Life magazine ad that elicited an amazing 150,000 responses) and its appealing, highly practical layout. While modest in size, the Lustron’s design successfully integrated evolving concepts of modern convenience with traditional ideas about the single-family domicile. Its bungalow-style layout attracted conventional devotees of the single family home; meanwhile, it offered the unusual convenience of fully integrated modern appliances, included in its base price.

Second among its lessons was its role as a test case for understanding the efficiencies required of house prefabrication. The company’s lack of discipline in limiting the number of dissimilar parts significantly reduced both the speed of factory production and site assembly. As architect Carl Koch recalled of his efforts to redesign the Lustron shortly before the company’s closure, a reduction in the number of dissimilar components, an increase in interchangeability, and a reduction of total component weight all would have reduced production costs and assembly time in the field.4 While the company did not last long enough to integrate his redesign strategies, the intended reduction from 3,000 dissimilar parts to 37 would likely have dramatically affected the Lustron’s prospects for success.

Although the Lustron’s populist design pedigree and strained financial history make it seem a distant cousin of more ‘heroic’ examples, there are significant parallels to be drawn. For instance, Frey and Kocher’s Aluminaire house substantially emphasized the use of new materials, most notably the “miracle metal,” aluminum. It was a sponsored exhibition pavilion intended for mass visitation, not unlike the Lustron prototypes, although mass production was never attempted. Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Dwelling Machine, similar to the Lustron, was to be produced in an aircraft factory by the Beechcraft Aircraft Company, with production anticipated at 200 per day or 50,000 per year. Its production fell through, however, when financing needs and Fuller’s own design objectives were not met. Wachsmann and Gropius’ General Panel house and early Package house also appeared to be headed for intensive mass production efforts at about the same time the Lustron experienced its best years, but the most successful General Panel house production effort only reached 150 to 200 units.6

Compared to such projects, the Lustron can rightfully claim a substantial success in prefabrication, albeit with substantial public investment. While it lacked the visionary pizzazz of Buckminster Fuller’s prototype, the Lustron Home reached the markets in numbers that few other experiments in prefabrication ever would. Evidence that the Lustron had captured the public imagination is surprising: in one city, for instance, nearly $200,000 remained waiting in escrow for production orders to be filled, while continued mail and telephone inquiries throughout its distribution areas overwhelmed the company. By the end of 1949, the Lustron Home’s distribution network included 234 dealers in 35 states, reaching from New York to Florida and South Carolina to Texas. North Carolina received the most houses (339), while Illinois (307), Ohio (275), and Indiana (142) also were leaders. Even North Dakota (12) and Florida (16) were represented, and a few made it as far west as Kansas and Texas. Although the Lustron experiment was distinct from other, more radical experiments in prefabrication, it offered a useful case study in execution which few other similar projects ever achieved. Not surprisingly, a large number of Lustron Homes still exists, spread widely throughout the Midwest and eastern seaboard. Current owners’ documentation of repair strategies, original sales information, and other historical details recall the impact of the experiment.7 They also remind us of the Lustron’s strange mix of visionary and pragmatic influences and the dream of a technologically advanced domicile for a new and better world.

1 H. Ward Jandl, Yesterday’s Houses of Tomorrow: Innovative American Homes, 1850 to 1950 (Washington, DC: Preservation Press, 1991). Jandl’s survey of experimental housing provides a useful reference for these examples. The other natural source for a summary of ‘heroic’ steel houses is Niel Jackson’s recent The Modern Steel House (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1997).

2 Thomas Fetters, The Lustron Home: The History of a Postwar Prefabricated Housing Experiment (London: McFarland & Company, 2002), p. 55. Fetters provides the most complete survey of the Lustron production history, including factors that contributed to both its creation and demise.

3 Fetters, p. 7.

4 Carl Koch, At Home with Tomorrow (New York: Rinehart, 1958), p. 122. Koch’s comments are valuable principally due to the timing of his involvement with the Lustron project. While his suggestions were apparently received too late to alter the course of the production effort, his investigation helps reveal some of the more important shortcomings at the time of a high rate of production. He questioned a number of managerial and design strategies that had been fundamental to the Lustron since its outset.

5 Fetters communicates these issues in a variety of locations, including p. 77.

6 Gilbert Herbert, The Dream of the Factory-Made House: Walter Gropius and Konrad Wachsmann (London: MIT Press), p. 304.

7 A variety of Lustron-related historical and photographic information resources are available on the internet, including: “Things you want to know!,” the Lustron brochure provided to buyers; “Lustron Registry, A list of Houses Across America”; “Garage and Breezeway Variations with Lustron Homes” (approximately 1950); “Answers to Questions about the Lustron Home” (Iowa Sales Brochure); “The Lustron Home—A New Standard of Living; A Camera Tour Through the New Lustron Home…The House America Has Been Waiting For” (July 1948 company brochure); “Camera Tour Through the Lustron Home, A New Standard of Living” (December 1948 company brochure); H. Walton Cloke, “Government Sponsored Housing Failure!,“ Stag Magazine, December 1949. Two such useful sites are http://strandlund.tripod.com (select “Pamphlets and Brochures”) and http://www.piranhagraphix.com/Lustron/ (current images are provided).

Author David Thurman is a senior associate at Barton Myers Associates in Los Angeles. The author thanks Edward Levin, Margaret Hannaford, Peter Robertson, and Sigrid Geerlings for their assistance with the development of this topic.

Originally published 3rd quarter 2002, in arcCA 02.3, “Building Value.”