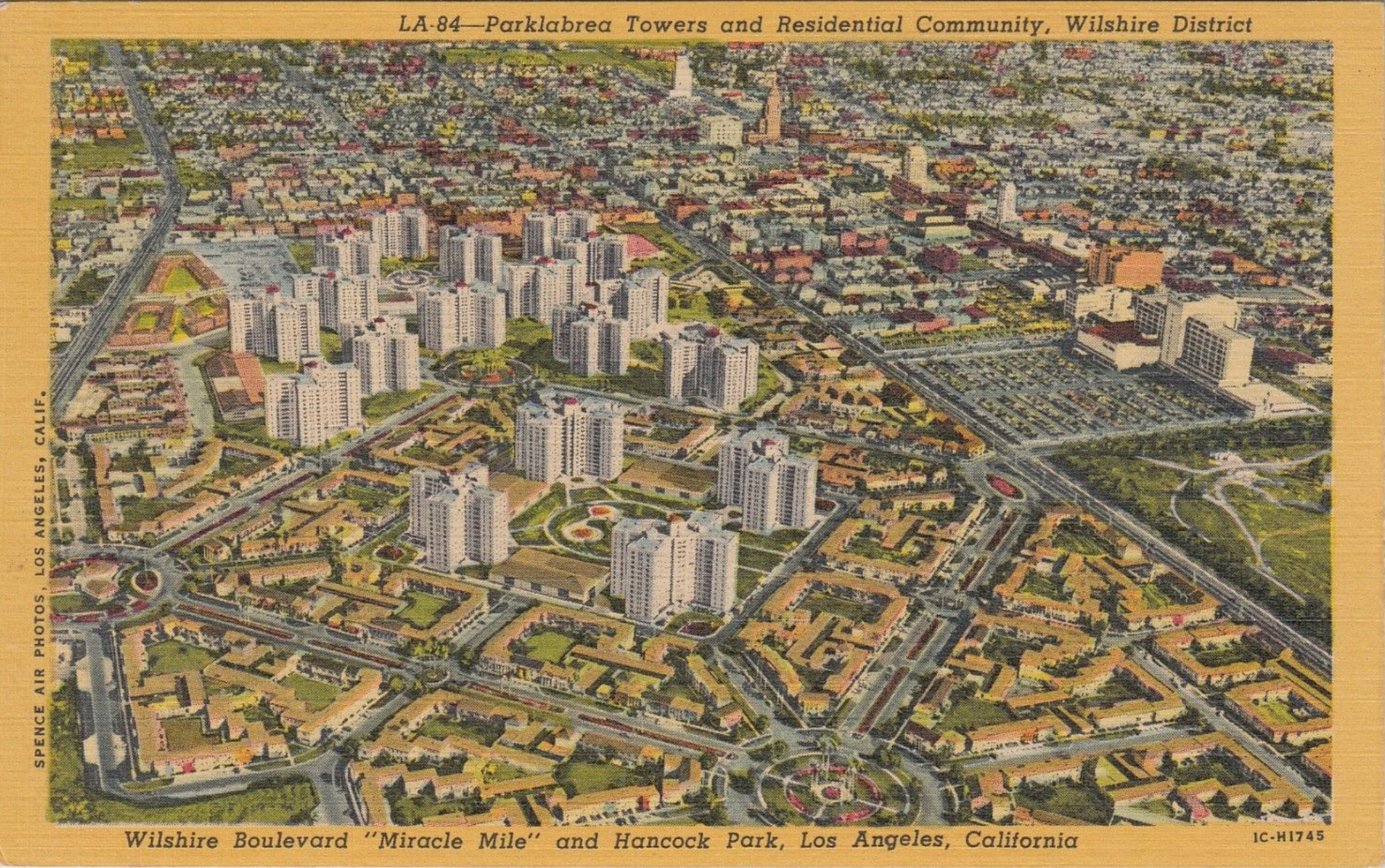

With enough altitude, the suburban neighborhoods of western Los Angeles merge into a uniform sameness – with one exception: Park La Brea. In the mid-twentieth century, on a remnant of Rancho La Brea, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company financed, built, and managed an uncommon design for Los Angeles living. Nearly all of Los Angeles is a variation on “a house in its garden”; Park La Brea is an island of apartment clusters and residential towers that both reflects and contests the city’s pattern of domesticity.

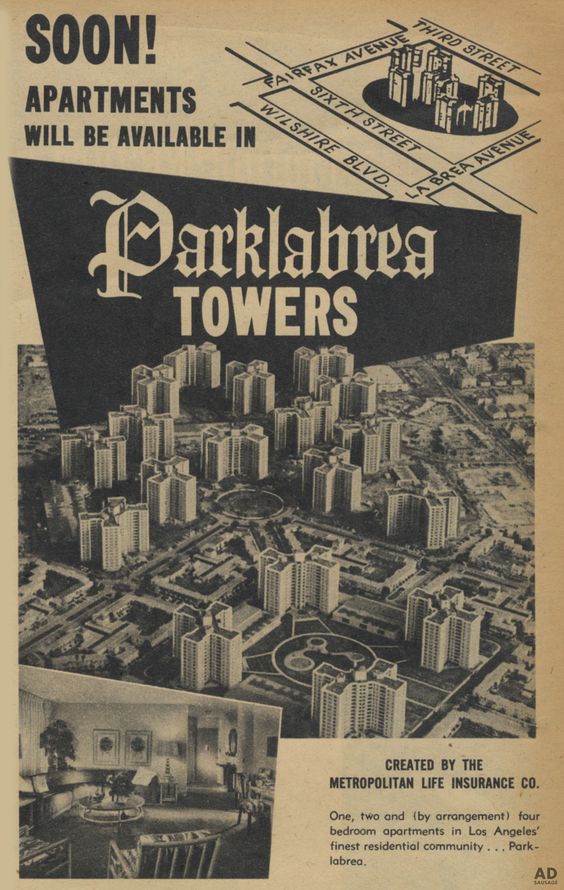

Beginning in the 1920s, Metropolitan Life had built structured communities to make structured lives, starting with Parkchester in the Bronx. In 1941, it embarked on four major projects: Parkfairfax in Alexandria, Virginia; Stuyvesant Town Center-Peter Cooper Village in Manhattan; Parkmerced in San Francisco, and Park La Brea (originally branded Parklabrea) in Los Angeles. The company was confident that it could develop a large parcel west of downtown with model apartments intended to improve the conditions of moderate-income renters. At Park La Brea, progressive design and the company’s watchful supervision would reinforce middle-class values, while leases would be at rates low enough that even hourly wage earners could step up from substandard units to modern rentals. Their design would confront the city’s exuberant architectural diversity with a tasteful and modest uniformity.

Work began in early 1941 on 176 acres acquired from the University of Southern California along the northern margin of Hancock Park. Although Wilshire Boulevard’s “Miracle Mile” was only a short walk away, the land had sold cheaply—just $1.5 million (about $26 million today). Leonard Schultze & Associates of New York produced the designs, with assistance from Los Angeles architect Earl T. Heitschmidt; Tommy Thomson was responsible for the landscape design. The site plan originally proposed 2,600 apartments in clusters of two-story units, each cluster enclosing a lawn bordered by patios. Inspiration came from Ebenezer Howard’s “Garden City” ideal as reinterpreted in the plans for communities like Radburn, New Jersey (1928), and Greenbelt, Maryland (1936). Unlike those developments, building entrances at Park La Brea were oriented toward the street, turning the interior of each apartment cluster into what looked like a small park.

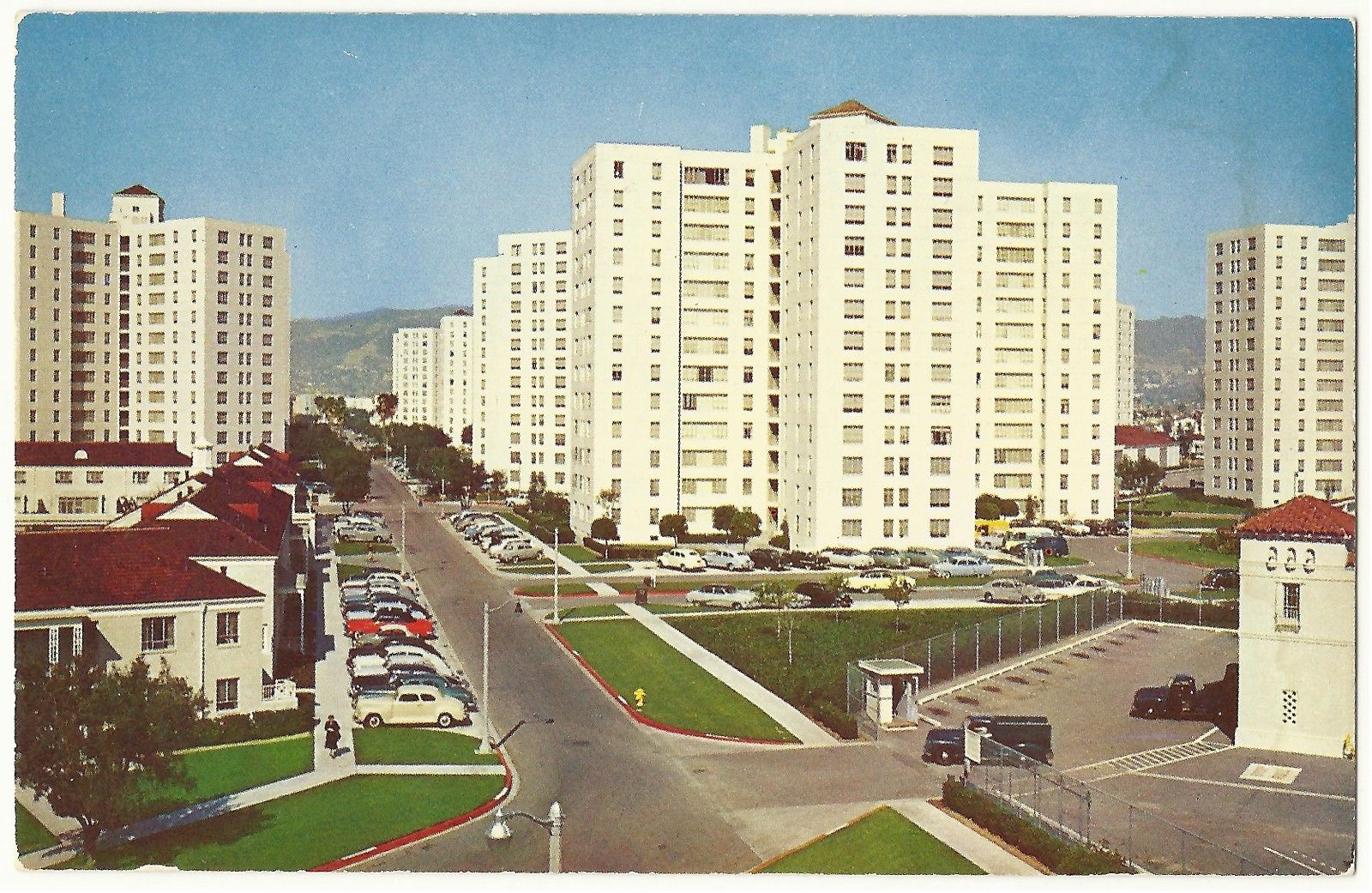

The scale of the clusters and their relationship to the out-of-doors responded to their context. The configuration of landscaped open space referred back to the courtyard housing and bungalow apartments of an earlier Los Angeles, where sunshine was synonymous with health. The two-story height limit answered concerns about urban encroachment on a neighborhood of small homes. With only 13 units per acre, density was not even double the surrounding, single-family tracts. Park La Brea’s architecture – stripped-down Georgian – was in the locally popular style called Hollywood Regency.

Park La Brea mirrored the city around it, but the reflection was distorted. The Los Angeles Times in 1941 thought the plan of Park La Brea was “in keeping with the California climate for outdoor recreation,” except tenants weren’t permitted to barbeque on their patio. Children were prohibited from playing on the lawns or leaving toys outside. Promotional materials emphasized broad windows that overlooked the lawns, as if the outdoors were mostly for observation.

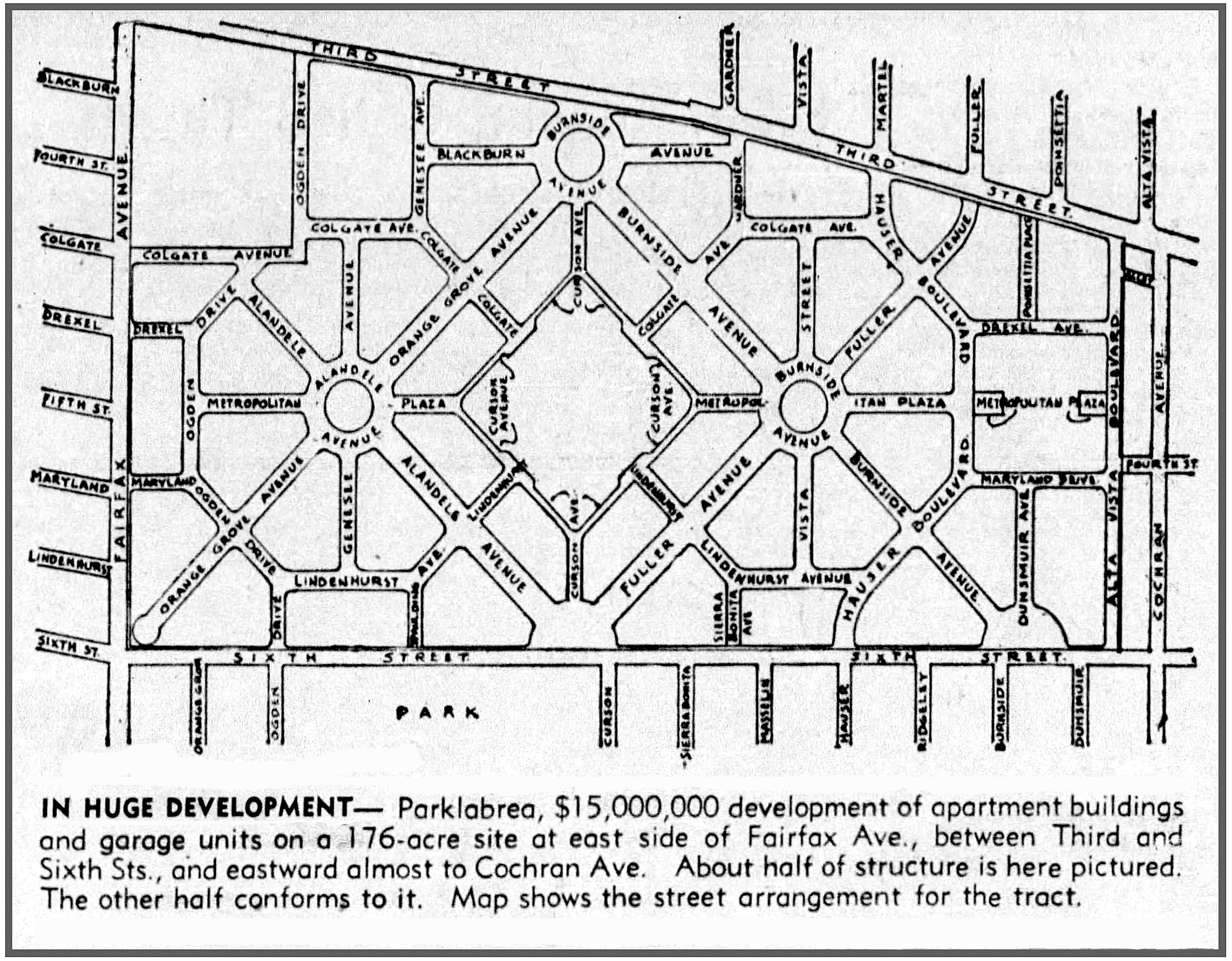

Park La Brea’s street plan created a further distortion. The surrounding neighborhoods were built on an orthogonal grid, but Park La Brea’s axial grid is as intricate in its geometry as a Tudor garden. It is a quincunx of octagons (two complete and two partial) overlaid by a diamond whose vertices intersect the roundabouts in the centers of the octagons (forming an inner quincunx). Streets radiating from the roundabouts cut roughly wedge-shaped plots in the octagons and rectangular plots within the diamond. The resulting street plan was bewildering. Visitors and pedestrians often got lost. One resident, quoted in a 2012 Los Angeles Times story, called it an “Orwellian maze.” It effectively limited traffic speeds but left Park La Brea aloof and inwardly focused, uninterested in the long vistas of the Los Angeles grid.

This inward turn was an accurate reflection of a sheltered, orderly, private, and racially exclusive mid-century Los Angeles. Metropolitan Life was earnest in its desire for social uplift, but only on the company’s terms. Lease agents manipulated waiting lists to exclude African American and Latinx tenants. There was a quota for Jewish renters: when the towers opened in 1951, Jewish tenants were limited to just two of them—a sort of high-rise ghetto—despite vacancies in the others. Young families were placed in apartment clusters on the periphery to spare older tenants the sounds of children at play. And vigilant management and snooping neighbors did more than keep children off the lawns. As the Los Angeles Times reported in 1993, “strict rules that kept everyone quiet” and a “uniformity that bordered on militaristic” gave tenants shelter from a boisterous and increasingly diverse Los Angeles.

World War II delayed and eventually stopped construction in 1944, leaving thirty-one, two-story apartment buildings completed and about a third of the site unbuilt. When development began again after 1948, the direction of architectural modernism had changed. The communitarian ideals of Radburn and Greenbelt had faded, the housing shortage was acute, and Metropolitan Life now put higher returns above social engineering. The second phase of Park La Brea was denser and taller, making the project one of the largest multi-family housing developments west of the Mississippi.

Build-out of the site was completed by 1951 with the addition of eighteen maximum-height towers (thirteen stories, a limit imposed by city charter), designed by Leonard Schultz and Associates with Kaufmann and Stanton, Architects. The stubby, X-shaped towers, each surrounded by a lawn, increased the number of rental units from 1,316 to 4,255 and the density to twenty-four units per acre. The towers were initially praised as a cost-effective interpretation of modernist architecture for a city suspicious of “Manhattanization” and hostile to public housing. Unlike the linear geometry of a Corbusian Radiant City, however, Park La Brea’s towers were fitted into the site’s fussy quincunxes. Quiet and distant, the towers penetrated the sea of Park La Brea’s garden apartments like a headland awash in breakers.

Contrasting images of urbanity sorted out lives in Park La Brea. The garden apartments appealed to tenants who wanted a familiar setting not far removed from the single-family tracts nearby; the towers were positioned for sophisticated consumers who were ready to adopt Park La Brea’s design for “metropolitan living” in suburbanizing Los Angeles. The apartment clusters were intimate and judgmental (much like the set of Alfred Hitchcock’s “Rear Window”); the towers were impersonal and outwardly focused as vantage points for surveillance and speculation on the city below. The apartment clusters were defined by Park La Brea’s street grid and oriented to it; the towers were indifferent to the grid and rose above it. Families with children chose garden units, while older couples and singles moved into tower apartments. Some garden apartment families stayed for years, but tower residents were more transient.

Metropolitan Life sold Park La Brea in 1985. New owners installed fences and gated the street entrances, giving historian Mike Davis another image of the “carceral city” he describes in “Fortress Los Angeles.” Park La Brea was sold again in 1995 to a limited partnership. Some older residents lamented the lack of community feeling, as Park La Brea’s ethnic demographics became more like the mid-city’s diverse community. There were renovations to the apartment units, but complaints about upkeep and tenant policies persisted. Limited-stay rentals have become a problem in recent years. Maintenance has declined. (Tenants won a $3.5-million judgment against Park La Brea in 2017 for the effects of a bedbug infestation.) Online reviews in 2018 depicted unhappy tenants and management focused on ROI.

Idealistic modernism and the practices of neoliberalism have not mixed well at Park La Brea. The low-rise buildings are almost 80 years old and expressive of values that depended on Metropolitan Life’s version of social housing and strict governance of tenants’ habits. The towers are nearly 70 and starkly assert a design philosophy no longer so utopian. Although Park La Brea gave western Los Angeles an urban-appearing skyline and had, for a time, joined the city’s few publicly financed housing developments in imagining what a future Los Angeles might be, the contradictions within Park La Brea and the rapid evolution of the city beyond rendered doubtful whether Park La Brea’s unreconciled images of urban life could ever have been a design for Los Angeles living.

__________

Author’s Note

I am indebted to historian Aaron Cayer, whose detailed analysis of Park La Brea – “Metropolitan Living: The Los Angeles Parklabrea Apartments” – appeared online in The Journal of Urban History, 2 May 2018. He graciously permitted arcCA Digest use of “Metropolitan Living” as a resource. My interpretation of Park La Brea and any errors are entirely my own.

__________

D. J. Waldie is a historian of Los Angeles whose books and essays consider how the past and present cities are connected through the built environment. He last appeared in arcCA with an essay, “What we lost when we came here,” in 2010. He was the 2017 recipient of Cal Poly Pomona’s Dale Prize for Excellence in Urban and Regional Planning.

__________