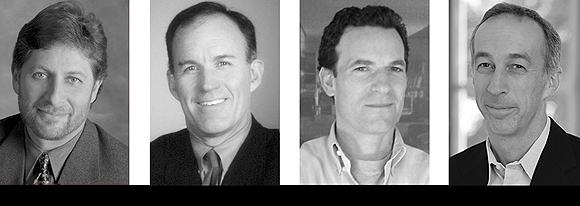

Clark Manus, FAIA, is a partner in Heller-Manus Architects, San Francisco. John McNulty, AIA, is a founding principal of MBH Architects, Inc., headquartered in Alameda. Cass Calder Smith is principal of CCS Architecture, San Francisco. Richard Stacy, AIA, is a partner in Leddy Maytum Stacy Architects, San Francisco. The interviews presented here with Manus, McNulty, Smith, and Stacy were conducted separately. We have interwoven them to highlight common themes and concerns.

Clark Manus: Jerry Weisbach is our father. He and, in a different manner, his partner, Ken Natkin. Jerry has a special place in my heart for what he’s done for the profession. He was an architect, he practiced, he taught, he became a lawyer, and then he helped the architectural profession protect itself from silly, rash decisions.

John McNulty: When we started our practice (MBH), the three partners realized that we were decent architects. We worked well together and respected each other personally. We were focused and hard working. We also realized that there were many facets to operating a business about which we knew absolutely nothing, so we sought advice from people we trusted. We contacted Jerry Weisbach and were fortunate to have Jennifer Suzuki and Steve Sharafian assigned as counsel to our new firm. Jennifer handles issues such as ownership transition procedures and the development of our Buy/Sell Agreement, as well as providing us with guidance in such areas as the nuances of mechanics liens. Steve provides us with insight into the development and administration of our agreements. With his guidance, we have developed our own proprietary Owner/Architect Agreement, as well as our own Architect/Consultant Agreement. We try to utilize these documents with as many clients as possible. Both Steve and Jennifer truly understand who we are and what we stand for. We don’t go anywhere without them, and we trust them implicitly. Steve could make a decision for me, and I would know it was one I would probably make. I wouldn’t put him in that position, but I could.

CM: Steve is very much like Jerry in his approach. Those people are there to help architects understand the legal consequences of our actions. There are probably those rare architects who really do understand the law. But the majority are not trained to see things in that way. The law is black and white in words, but people can make the words say whatever they want. I’ll read a paragraph and go to them and say, “I think I understand this, but tell me the scenario under which it would unfold.”

JMcN: Steve is a great teacher, with a disposition that is immediately calming and reassuring. He has a wonderful sense of timing and knows when to let you ramble on and on and when to interject. He has always provided sound advice upon which we can make informed decisions. He understands the kind of clients that we deal with and how to recognize their posturing and strategizing.

Richard Stacy: We want to understand what we’re agreeing to, rather than just saying, “Our attorney looked at it; I guess it’s OK.” I have clients who have that attitude; they don’t want to bother with it, but that’s not our philosophy. So, half his job is explaining to us what the legal concepts are and implications are, so that we can make an informed decision and have a more intelligent negotiation.

CM: It’s a very difficult field. You go into graduate school to be an architect. How glamorous, how cool. Neat profession. You get to do all these things. You get through school and begin to work. You’re a grunt. You’re basically drawing details. Probably nobody explains to you the consequences of what you’re drawing. At some point along the way, when you make the transition from being part of the project team to running the job, and then to principal or firm owner, the legal consequences are daunting. You’re looking for somebody to call you at night and make sure that you can understand the consequences of your actions.

Using Lawyers

CM: A lot of architects are not sure how to use lawyers well. They say, “Just write me a contract and I can give it to my client,” rather than using their lawyer’s help to understand what the strategy should be and figuring out now to avoid spending lots of money on legal fees arguing about stuff that doesn’t mean anything.

Cass Calder Smith: It’s great to have the ability to call your attorney for a rapid answer to a client’s objection to a contract clause. When a client tries to get clever, picking apart the AIA contract, it’s good to be able to say, “I’ll have to check with my attorney.” It’s nice in a negotiation to be a two-headed party— with your partner, or your wife, or your attorney—because it gives you time to think about the issue. It’s almost always a mistake to agree on the spot. And this is one of the most important things I’ve learned from attorneys: the importance of being patient.

RS: Some people operate such that anything that’s drafted by an attorney they automatically send to their attorney, but maybe because I’m married to one and have done this long enough, we don’t automatically do that. I’ll go through it first, and if I don’t understand something, or we’re not sure what the implications are, we’ll ask specific questions. They’re much better at drafting alternative language than we are.

JMcN: In order to get the most from your advisors, it is important to keep them informed. Never surprise them with last minute issues. It is incumbent upon the architect to keep your attorney—and your insurance broker—aware of your projects and to let them know the status of your high profile projects on a regular basis.

RS: Land use attorneys are the ones we spend the most time with. They’re almost indispensable these days in getting project entitlements. They’re down at the Planning Commission, every meeting, and they know all the players. You don’t want any surprises at the commission meeting. You want to know where everyone stands ahead of time, because you never know where a discussion might go if you don’t. So, they’ll canvass members we probably couldn’t get access to and find out what their hot buttons are, so we can address them up front. And even if we end up not convincing someone to support our project, at least we know what their issues are, where they stand. The ideal scenario is, when you get to the commission meeting, you already know what the outcome is.

Teaching the Client

CM: The public believes that buildings are like cars. “I bought this design, you designed it for me. Don’t I get a warranty? When it breaks in fifteen years, don’t I call you up and you come and fix it for me?” Steve helps educate about such simple things. What’s the difference between providing architecture as a product versus a service? “I want you to design this building for me, but keep in mind I may sell the project to somebody else, and I want to be able to sell those drawings with it.” Wait, time out. I’m not designing your product, okay? I’m providing a service. Sure, we can part company, but there are parameters guiding what you can and can’t do with it. Steve gets into that gray zone where you’re not talking about creating a paragraph for other attorneys to review. You’re talking about how you approach a subject with your client, about what it is to provide architectural services.

RS: I mentioned that my wife is an attorney. One thing I’ve learned from her on a professional level is the art of thinking and writing clearly. She feels strongly that legal language is often overly complex and jargon-filled, that it doesn’t have to be, and that the better product from an attorney is something that is clear. It’s something that a good attorney has been well trained in, and something that I value a lot more than I did before I knew her, and I think I’ve gotten better at it.

CCS: Residential clients are sometimes naïve about what we provide. We try to come across as professional not only in creative terms but also in business terms—timelines, thoroughness of proposals, etc. Most people can relate to the business side of things and appreciate working with others who do.

JMcN: Effective communication is an art form, and I do believe that we get better at it as we mature in this business. An architect must first seek to understand all of the issues from the client’s perspective, design and scheduling issues as well as contractual issues. Contracts should be fair and balanced. We strive to act as professionals at all times, and we expect the same from our clients. Your first glimpse into the future relationship with your client will unfold during contract negotiations, and it is vital to have a clear agreement in place before you proceed. An architect should understand the value of their agreements, the scope of work and responsibilities that are delineated in order to manage the risks. During contract negotiations, we want to show our client that we scrutinize every detail and that this trait is an indication of how vigilant our firm will be in all aspects of the relationship. There was a situation once in which I told a client, “If an architect actually signed this agreement, I would fire them on the spot. This is the most poorly written agreement I have ever read, and anyone who would sign this either did not read it or did not understand it. Either way, you do not want to work with them.”

arcCA: Did that increase your credibility with the client?

JMcN: [laughs] No, not that time. We felt good about it, though. It’s immoral to agree to something you can’t do.

Negotiating Contracts

JMcN: Architects are born with a passion do things at an “all or nothing” pace, and we are always striving for perfection. Despite this emotional attachment to perform architecture to the very highest level of our abilities, Steve has always been very clear that we must define the standard of care within our agreements as negligence. We are not perfect. Our contracts must acknowledge that the architect does not control everything and that the practice of architecture is performed by human beings.

CCS: Lawyers can help with limitations of liability that won’t scare clients away and that can also help to lower insurance costs. And they help structure consultant involvement in ways that can limit liability.

JMcN: Our practice includes relationships with many corporate clients; therefore we often negotiate Master Agreements. Steve has been a tremendous asset in understanding the differences in the scope of work and the risks involved with each relationship and how to differentiate and manage those risks. We must understand the responsibilities that the firm has signed up for, the scope and the schedule of the work and how these corresponds to the fee, how we are going to be paid, what we are expected to produce over what period of time, and how much insurance we are providing to our client and for how long. We have come to describe ourselves as a business that provides architectural services. Architecture is an important—even fundamental—component of our culture, and it is up to us, as architects, to help society recognize it, so that we are compensated fairly.

CCS: Always insist on a quid pro quo: we’ll limit our fee if we can limit the scope.

CM: In public projects, cities demand indemnification from architects. But it’s uninsurable. What am I going to do? The attorney says it’s your choice. You can make a business decision and sign the contract. You can resist and try to change it. And if you can’t change it, you’re just going to be back to your business decision. I hear this a lot from Steve: I’ve crossed the point where I can be your language attorney; I can advise you, but you need to make a business decision based on what you’re going to get out of it and the risks. At the end of the day, you need to make the decision. Your lawyer can’t make it for you.

JMcN: Jennifer has stepped in many times to provide us with guidance when we have difficulty in getting paid for our services, usually toward the tail end of large projects, when the posturing begins. She really understands the concepts behind lien rights, how to protect them and how to effectively use them.

CCS: About 40% of our work is restaurants. With restaurants, getting paid is often hard. We now require a personal signature from the corporate director, so that both the corporation and the individual are responsible for the bill. It’s best to get paid up front for each phase. In one case, we were asked to do a project by a client who was notorious for refusing to pay his architects for completed work that he claimed was in some way inadequate. But it was an interesting project, so we negotiated a process whereby I met with the client every Friday to review that week’s work and have him sign off on it. Then he would pay in advance for the following week’s work. Things went fine.

arcCA: At this year’s Desert Practice Conference, the big topic was Building Information Modeling. One heard a lot of questions concerning the fear that, if a set of documents becomes much more comprehensive, so will the architect’s liability.

JMcN: We all have heard many times that “the architect screwed up!” We always seem to be the first ones to blame for a problem on a project, so it would seem that anything that changes or advances construction techniques will have an impact on our liability. We always demand to have a clear Means and Methods clause within the agreement to accurately delineate the contractor’s role during construction. Recently, Jennifer Suzuki asked me if we ever thought about doing work in Asia. I said we have, but we didn’t want to do any work that would distract us. Everybody has twenty-four hours a day to live, for however many years you get to spend here. You have your family and all the other important things in your life. Our goal is to have a workplace that is energetic and fun, that is focused and professional, and that can be counted on to perform at the highest level at all times. If we can live up to those goals and manage our risks properly, by structuring fair contracts and fulfilling our responsibilities, than we will be financially profitable. Distributing the wealth throughout the firm will keep our great team together. And we can maintain balance in all aspects of our lives.

Originally published 1st quarter 2005, in arcCA 05.1, “Good Counsel.”