During the past two decades, environmental racism—the disproportionate exposure of people of color to environmental hazards, as well as their exclusion from benefits associated with environmental amenities—gained broad political and social attention, stimulating the rise of a powerful social movement focused on environmental justice. In major metropolitan areas, lack of access to green space—especially parks and recreation facilities—has become a particularly salient environmental justice issue and focus for organizing. Historically, urban parks were widely deemed to be representations of nature that would promote a better society by combating such social problems as poverty, crime, and poor health, and by providing major benefits such as better public health, social prosperity, social coherence, and democratic equality. Today, many of these same reasons for building parks are offered to justify parkland acquisition and facility construction, especially given mounting evidence that access to parks and recreational resources is critical to obesity prevention. But the distribution of park and recreational resources remains a source of social injustice and public health concern.

In this article, I focus on the scale of environmental justice problems associated with access to public “places to play”—namely, parks and recreational resources. I also raise the prospect of potential solutions that ask us to recast the “negative” space of the city—alleys, vacant parcels, vacated streets—as green infrastructure for physical activity, play, and ecosystem services that make for a healthier city. Drawing on my past research, conducted with colleagues and graduate students, on the distribution of park space in Los Angeles, the congestion of park space, and the pattern of public recreational programming across the region, I highlight the profound race/ ethnic differences that exist in access to parks and playspace. At the same time, our new studies of a neglected urban land resource show that one productive strategy to address lack of access to environmental amenities in Los Angeles is to look, if not exactly in your own back yard, then out to your own back alley as a source of inspiration and place to play.

Access to Urban Parks and Recreation as an Environmental Justice Issue

Environmental justice issues have long been especially salient in Los Angeles. Historically, LA’s low-income people and communities of color faced not only economic discrimination and social marginalization, but also environmental racism. For example, in the early years of the 20th century, on the east side of Los Angeles, industrialization prompted growth. As more factories were being built, a greater need for low-wage manufacturing workers arose. Some evidence suggests that communities of color—which are typically weak politically— were preferred sites for certain types of polluting facilities, such as toxic storage and disposal. Also, some cities deliberately created housing for minority workers in close proximity to industrial facilities. Not surprisingly, people of color are currently more likely to be exposed to environmental hazards in Los Angeles and face higher rates of lifetime cancer risk.

Public policy played an important role in shaping patterns of environmental injustice. For example, the City of Los Angeles’s 1904 zoning code, the first in the nation, protected the affluent, predominantly Anglo Westside from such industrial uses. Higher-density housing, commercial, and industrial activities were allowed to locate by right in the city’s eastern and southern areas in which lowerincome workers, including people of color, were concentrated. Public park resources, never very generous in a city whose domestic ideal was the single-family home with private backyard, were disproportionately allocated to other parts of town.

Past discrimination in housing and employment, ongoing environmental racism in the siting of industrial and other polluting facilities, and inequitable distribution of parks and other urban services, mean that low-income households and communities of color in Los Angeles are apt to be relegated to “park-poor” neighborhoods. This deficit in parklands is particularly problematic for older, high-density, low-income LA communities where children tend to utilize park resources more intensively than kids in newer, suburban areas, where most housing units have gardens and there are more recreational opportunities in the environment. In addition, urban nature offers more than just amenity value. Rather, soil, trees, and other vegetation provide ecosystem services that reduce ambient heat levels, act as pollutant and carbon dioxide sinks, and absorb polluted urban runoff, thereby helping to mitigate issues of disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards. Therefore, not surprisingly, the issue of parks and recreation is commonly cited as one of the most critical among residents of the city’s low-income communities of color.

Patterns of Park-Poverty in the Los Angeles Region

The distribution of park resources is highly uneven across racial/ethnic communities of the city. In a study that defined communities according to their predominant race/ethnic population and then considered local access to park space, John Wilson, Jed Fehrenbach, and I found that Latino and Asian-Pacific-Islander neighborhoods had the highest population densities, followed closely by African-Americans; densities in all three types of neighborhoods were two to five times higher than in White-dominated neighborhoods. Latino areas, with two-thirds of a million children, had almost three times as many children, living at five times the density as residents in heavily White areas. Yet those areas with 75% or more Latino population (188 census tracts, with over 770,000 residents) had only 0.6 park acres per 1,000 population, and heavily African-American dominated tracts (11 census tracts with almost 50,000 residents) had 1.7 park acres per 1,000 population. In comparison, heavily White dominated areas (117 census tracts with almost 480,000 residents) enjoyed 31.8 park acres per 1,000 residents.

In another study, Chona Sister, John Wilson, and I employed the “park service area” approach to understand “who’s got green?” in the broader southern California region. This approach assumes that every resident utilizes the nearest park at some uniform rate, a broad but generally supportable assumption. This allowed every neighborhood space—and thus every resident—in the region to be “assigned” to his or her closest park, thus delineating a park service area (PSA) and its associated population. The ratio of PSA population to acres of park space is an estimate of potential congestion or “park pressure” for each service area. The National Recreation and Parks Association (NRPA) historically recommended 6 to 10 park acres per 1,000 residents; although a rough measure and no longer officially utilized, this standard captures distributional equity across metropolitan regions. Translated to park pressure, this standard equates to approximately 100 to 167 persons per park acre (or “ppa”).

Only 403 PSAs or 24% are within this range or better, leaving 1,271 PSAs or 76% with park pressure levels higher than the recommended standard. In terms of population, only 16% enjoys levels of park access that fall within the NRPA standard. Not surprisingly, PSAs with lower park pressure typically contain larger greenspaces, while high park pressure areas have small parks and high population densities, and are mostly located in the central LA basin. Latinos are more likely located in PSAs with high park pressure, with the proportions of Latinos increasing as park congestion levels increase. The African-American population also exhibits this same trend, although to a less extreme degree. The proportion of Asian-Americans in the region did not exhibit a consistent discernible trend relative to the park pressure classes. Not surprisingly, PSAs with relatively high densities of children tend to have worse park access, as do low income people.

Park space is an important amenity, but recreation programs are also crucial, especially in terms of rates of physical activity, with attendant implications for public health. Recreation activities are not evenly distributed across metropolitan Los Angeles. In a study that I conducted in collaboration with Nicholas Dahmann, Pascale Joassart-Marcelli, Kim Reynolds, and Mike Jerrett, we analyzed data on the location and characteristics of recreational course offerings that provided opportunities for moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in cities across the region. We found that recreation programs were profoundly uneven in their distribution, with variations particularly stark with regard to race and ethnicity. Cities with greater proportions of White residents tended to have more opportunities for recreation programs in comparison to those with more Black and Latino residents. Similar variations existed based on fiscal capacity, whereby cities with limited fiscal resources suffer from reduced recreation opportunities. Even when controlling for a variety of socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of cities, these patterns of environmental injustice prevail.

Alley Greening as an Environmental Justice Strategy

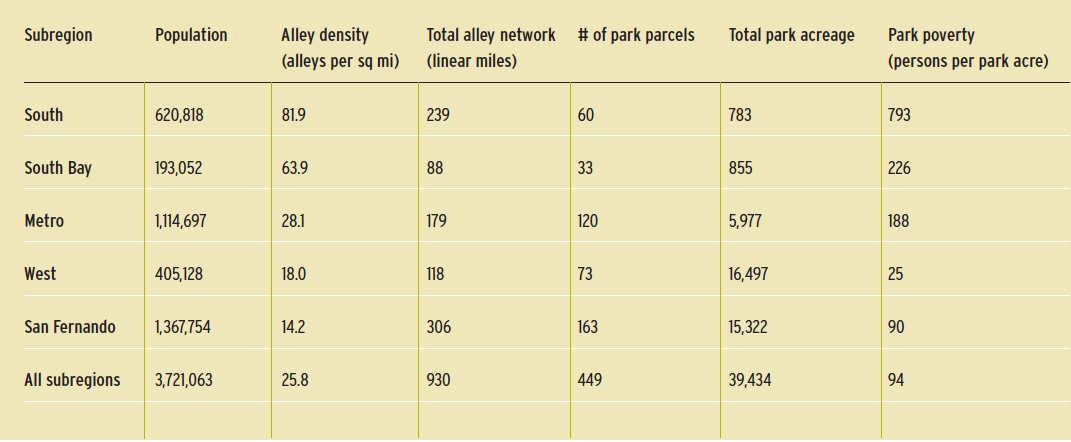

One innovative strategy starting to gain currency among cities, including Chicago, Baltimore, Vancouver, and Los Angeles, is to “green” long-neglected back alleys to enhance access to urban park and playspace, achieve public health goals, and increase urban sustainability. Alleys are a significant but typically overlooked public infrastructure resource of the urban landscape—they are classic examples of “terrain vague.” In the city of Chicago, for example, there are approximately 1,900 miles of alleys, comprising more than 3,500 acres. The city of Los Angeles has an estimated 12,309 alley blocks, a network of more than 930 linear miles, or approximately 1,998 acres, while Baltimore’s alley network encompasses over 600 linear miles. This represents a sizable underutilized urban land resource, particularly for those neighborhoods that suffer from park poverty.

Why are alleys so neglected? For more than two thousand years, alleys have been a feature in urban design, serving as spaces for neighbors to interact, as access points for infrastructure services, and for a variety of other purposes. In the U.S., alleys fell into disfavor in the late-nineteenth century, because they were often seen as dangerous, unhealthy places. By the 1930s, federal housing policy officially disallowed alleys, and urban design and municipal services evolved to focus attention on front yards.

But revitalizing alleys as a means to provide social and green infrastructure for urban areas has great potential. Green alleys can provide a variety of ecological services, such as urban rainwater management through runoff filtration, groundwater recharge, heat island reduction, wildlife habitat, and urban forest cover. As safe, attractive, usable social spaces, converted alleys can help renew neighborhoods by fostering increased visibility and use of previously underutilized, feared spaces. And they can provide park and recreational space for park-poor neighborhoods.

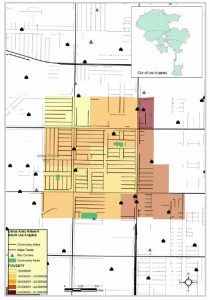

A detailed study of alleys in Los Angeles that I conducted with Josh Newell, Mona Seymour, Jennifer Mapes, Kim Reynolds, and Hilary Bradbury, provided the empirical data and policy design necessary to transform alleys into green urban infrastructure. The central question was: What if the city’s 930 miles of alleys were transformed from ambiguous spaces into valued places? Alleys are widely but unevenly distributed across the city, with alley density (alleys per square mile) being much higher in older communities in South LA and the South Bay, than in West LA or the San Fernando Valley (see table opposite).

To highlight possibilities, one particularly park-poor, low-income community in South Los Angeles with a dense alley network was studied as a hypothetical planning scenario.

A low-income community of almost 60,000 Latino and African-American residents, this part of South Los Angeles is characterized by older single family and multifamily housing. Obesity and related chronic disease rates are high, and so are rates of failure in the State of California body composition test of school children in grades 5–12, highlighting the future health risks facing this community’s children and youth.

Park poverty is severe here; the community has just three parks (22 acres), roughly one park acre for every 2,593 persons. Yet this park-starved area is alley rich, with 577 alley segments or 160 alleys per square mile, almost eight times the city average. With 40.12 linear miles, the area of this network is approximately 87.5 acres, or more than four times the community’s existing parkland. Converting these alleys into greenspace would dramatically reduce park congestion or “pressure” to roughly 528 people per park acre. Although this is still much higher than the citywide average, and not all alley space could literally become parkland, an alley conversion strategy would still entail a radical reduction in park poverty.

In such contexts, the alley network is a significant untapped public resource. Redesigned in simple, cost-effective ways, safe, clean and green alleys could facilitate walking and informal recreational use via the provision of micro-exercise equipment sites, park benches, swings, and other infrastructure for local residents.

Conclusions

The extent of residual urban land varies widely from city to city. Few studies have systematically considered how such parcels could be aggregated and reconceptualized as green infrastructure that might simultaneously address environmental injustices in the distribution of places to play. Yet the days of expansive single-purpose suburban-style parks and playfields may be over. Environmental designers can create alternative, multi-benefit networks of urban greenspace and, in so doing, promote social and environmental justice in the city.

Author Jennifer Wolch, PhD, is Dean of the College of Environmental Design and William W. Wurster Professor of City & Regional Planning at UC Berkeley. She was previously Professor of Geography and Urban Planning and Founding Director of the Center for Sustainable Cities at the University of Southern California.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2010 in arcCA 10.2, “The Future of CA.”