California’s evolving historical self-awareness can be attributed, in part, to the fast-growing and controversial effort to preserve works of the “recent past”—works designed and constructed between the years 1945-65. In California, such works are seen as part of the state’s cultural patrimony; California designers can justifiably take credit for many of the period’s iconic buildings, landscapes, furniture, and other designed objects. Yet, the new interpretation of Modernism visually integrated buildings with their landscapes. Consequently, “seeing” the resulting postwar works at all, much less as historically significant, has been challenging for the general public, as well as for hard-core preservationists.

The individuals leading the charge for the preservation of the recent past are often relative newcomers to the field. In northern California, the local chapter of DOCOMOMO (Documentation and Conservation of Buildings of the Modern Movement), based in San Francisco, is the principal group agitating for preserving Modern works. In southern California, the Los Angeles Conservancy’s Modern Committee (Modcom) is a feisty group of preservation advocates. Individual cities with important collections of postwar resources, most notably Palm Springs, have promoted the preservation of their historic Modern buildings and, in the process, have tapped into a new tourist market. In 2004, in response to these concerns, the State Historic Resources Commission formed a statewide committee to focus on the architecture and landscape architecture of historical significance to the Modern era, and the issues peculiar to their preservation.

Some of the difficult issues associated with the preservation of Modern resources can be illustrated by two recent cases. The construction of new condominiums on the site of the Stuart Company (Edward Durrell Stone, architect; Thomas Church, landscape architect; Pasadena, 1958) raises questions about balancing preservation considerations with civic plans, however well intentioned. Even more controversial, efforts to preserve the Lincoln Place Apartments (Ralph Vaughn and Heth Wharton, architects; Venice, 1950-51) have sparked nothing short of class warfare, with affluent property owners pitted against low-to-moderate income tenants.

Integrated Landscape and Architecture: Stuart Pharmaceutical Company

The City of Pasadena is known for its Arts-and Crafts-period neighborhoods and Beaux-Arts Civic Center, but, during the postwar period, the Pasadena Chamber of Commerce invited manufacturers to establish facilities in the City, particularly if they were associated with scientific research. A number of existing or new firms established facilities in the eastern section of Pasadena, where land was available for larger plants and housing tracts to accommodate the projected influx of new employees. The Stuart Company is, without question, the complex that most fully embodies the concept of the postwar “suburban factory” in Pasadena. It was a pharmaceutical manufacturing and office building, a collaborative effort by architect Edward Durrell Stone and landscape architect Thomas Church, which the AIA named as one of the best buildings of 1958.

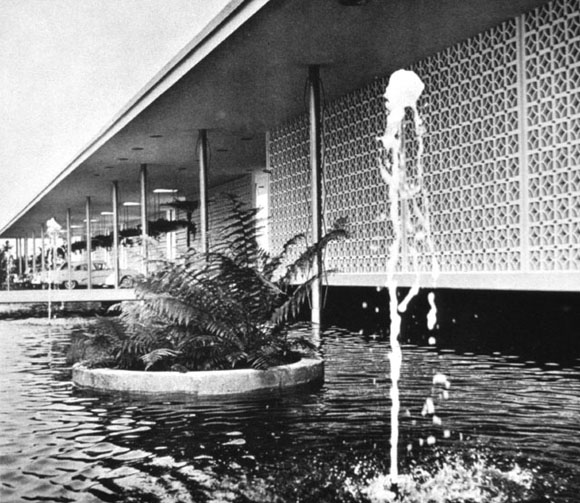

Set back approximately 150 feet from East Foothill Boulevard, a main arterial road, the massive building, which occupied about one quarter of its 9.4-acre site, appears modest and fragile. This effect was achieved by nestling the building into the downwardly sloping site. From the road, the complex reads as a series of low, horizontal elements (exemplifying the type of architecture that is invisible to many). Church designed a landscape of planters, lawn, and a shallow moat; the building hovers above this setting. Stone’s signature cast concrete block screen spans the width of property, uniting the building facade with a series of parking bays.

The Stuart Company was sold in 1991 to Johnson and Johnson/Merck Pharmaceuticals Co. and was later acquired by a public agency, the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA), around 1994. Out of concern for the fate of the building, Pasadena Heritage, the local historic preservation non-profit organization, prepared a National Register nomination for the property, and it was listed in 1994. Unfortunately, the National Register nomination played down the significance of the landscape design. This attitude, landscape historian Charles Birnbaum suggests, is symptomatic of the “invisibility” of modern landscape architecture to many involved with the documentation of historic sites.

In 2000, the City completed its East Pasadena Specific Plan, in preparation for construction near the new Gold Line light rail service linking Pasadena with downtown Los Angeles, which opened in 2005. (Originally, the MTA intended to construct a transit station on the site of the Stuart Company, but then limited their construction to a parking structure located between the building and the 210 Freeway.) One of the commendable goals of the Plan is the promotion of Transit Oriented Development (TOD), and, more specifically, mixed-use or residential development. The Plan calls for 400 housing units to be constructed within the general area that includes the Stuart Company site, with the proviso that the “preservation of the most significant portions of the Stuart Company building and its landscape [are] mandatory.” The Plan anticipated that portions of the Stuart Company might be lost in order to allow area for new construction. This conjecture (and sanction) has been realized with the demolition of the rear fifty percent of the original building in 2005.

A private developer came forward with a project to develop 188 one- to three-bedroom and loft units, with parking for 296 vehicles. Currently under construction are three stories of housing above a raised parking lot on the site of the demolished portion of the Stuart Company. Additionally, two stories of housing are being constructed around the east side of the property, framing an existing pool area. The project, as reflected in approved documents, is sensitive in its treatment of the front portions of the buildings. Similarly, the landscape treatment for the planters and other areas visible from Foothill Boulevard appears to be carefully assessed. However, the new construction bears little relation to Stone’s highly significant architecture in either its composition or detailing. Also problematic is the treatment of the pool area. In the new project, the pool remains, but the bathhouse and the surrounding landscape architecture have been replaced by new vegetation. A large, molded plywood shade pavilion—an extremely important sculptural element of the exterior design—has been removed and relocated to a city park; unfortunately, the plywood panels have been replaced with concrete shells. The new landscape features reflect a southern California Mediterranean landscape tradition rather than a response to Church’s Modern aesthetic.

Property Values and Class Warfare: Preserving Lincoln Place

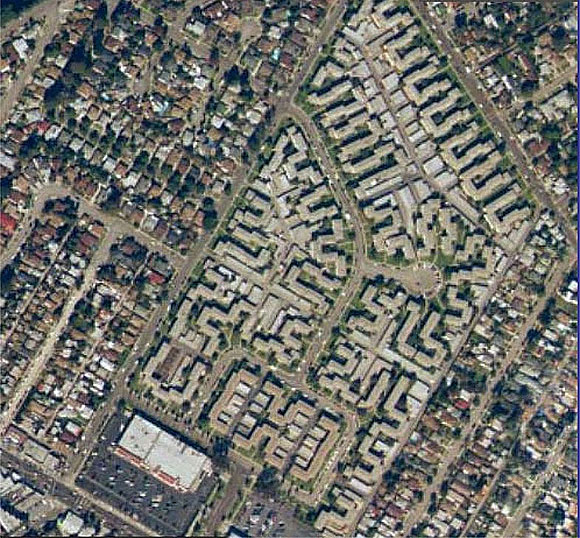

The beach community of Venice, California (distinguished by canals and arcaded buildings that refer to its Italian ancestor) prides itself on being one of the “funkiest towns of America,” home to “artists and visionaries, musicians, entertainers, weightlifters, and many others.” The existence of affordable rental housing is necessary to support these lifestyles. Yet, the soaring value of coastal real estate has made it difficult to maintain reasonably priced housing in Venice. Lincoln Place Apartments is the battleground where these competing social and economic values are playing out. This postwar garden apartment complex was originally comprised of 795 one- and two-bedroom apartment units in fifty-two buildings, sited on thirty-eight landscaped acres of prime real estate.

The case for the historic significance of Lincoln Place Apartments rests on its association with the history and aesthetics of postwar garden apartment development. Lincoln Place was privately developed with the assistance of Federal Housing Administration (FHA) Section 608 Mortgage Insurance. (Section 608 was a 1942 addition to Title VI of the National Housing Act of 1934, intended to increase the number of rental units for defense workers.) Funding for this program increased exponentially after the close of World War II, in an effort to alleviate the critical national housing shortage. More than 400,000 apartment units were built with Section 608 funding, in which rents were kept low.

The FHA published a series of brochures illustrating guidelines for the layout of housing complexes and individual unit plans. It recommended housing blocks framing landscaped courtyards and advocated low to medium density for the entire site, with segregation of pedestrian and vehicular traffic, and buildings designed to convey architectural unity but avoid monotony. As in earlier episodes, the concept of a landscaped, low-density housing development was thought to be conducive to the creation of a harmonious community. At Lincoln Place, such a community was created and thrived for more than fifty years. The project was considered a model of what could be accomplished within the limitations imposed by the FHA; later recipients of FHA mortgage insurance were sent to Lincoln Place for inspiration.

The current owners (and they have changed over the last few years) have demolished seven of the original buildings and evicted all but fifty households of senior and disabled tenants. An early scheme proposed to demolish the site and construct 708 condominiums and 144 affordable units. After protracted discussions and, more recently, mediation sessions, many of the original units (as many as 450 to 500) may be retained; however, the number of new units has not been settled, nor has the fate of the evicted tenants. Whatever the ultimate outcome, a thriving community of middle- to lower-income residents has been destroyed.

The impact of the Lincoln Place issue is not limited to Venice, Los Angeles, or even California. Its repercussions have been felt in our nation’s capital. The case has been used to challenge state and national historical preservation laws. Attempts to list the property at a local level—as a Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Monument—failed. The State’s Historic Resources Commission and the Historic Preservation Officer found the property eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places (February 2003), but the National Register staff, in Washington, D.C., returned the nomination with a request for additional information. Subsequently, the State Commission has found it eligible twice for the California Register of Historical Resources. (The first time, the Commission’s vote was challenged on technical grounds.)

While individual Modern houses may be highly valued, there is still much work to do in getting Modern commercial, industrial, and multi-family complexes recognized as worthy of preservation efforts, especially when increasingly dense urban areas are in search of developable properties. Both public agencies and private developers need to be educated—and when that fails, preservationists must be unafraid to use the legal tools available to them.

Author Lauren Weiss Bricker, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of Architecture, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. She is immediate past-chair of the California State Historical Resources Commission, where she founded the statewide Committee on the Cultural Resources of the Modern Age. She is the author of a forthcoming book on the Mediterranean house in America (Abrams, 2007).

Originally published 3rd quarter 2006 in arcCA 06.3, “Preserving Modernism.”