Cecil Williams Glide Community House

Interview with Michael Willis, FAIA, the founder of his namesake firm. The firm’s Cecil Williams Glide Community House in San Francisco received a 2003 Merit Award.

arcCA: It’s been a few years since Cecil Williams House first opened. How has it held up? What about the experiment of a high-rise for the homeless?

MW: The on-site social services are the key factor that makes the project successful. The network of support, job training, and recovery alleviates the isolation one might feel living in a high-rise. Support is all around you, so you don’t really have the opportunity to opt out. Having a voice to turn to when you feel alienated is a great help.

When the building first opened, there was a concern for how the homeless people would treat their building. Because of the “gentle” social network, their sense of ownership has happened. The residents identify with the building, not just their apartment. It starts at the front desk and goes all the way to the roof deck that overlooks the city. The residents are not ashamed to live there, they are proud. I am never worried about what I am going to find there when I show it to clients. People still walk in thinking it is a nice hotel.

arcCA: Can this experiment be replicated?

MW: I think the kinds of developers who are interested in replicating this idea are developers who have a sense of social mission. We are talking with another church group that wants to develop housing. Like Glide, they would offer social services as part of managing the building. It would be for low-income families. They are hoping for a financial return so they can build more.

arcCA: What’s happening with affordable housing across the country?

MW: At the AIA Grass Roots Conference this spring, someone representing the President’s Council of Economic Advisors explained why cutting housing subsidies is a good idea. After he left the room, we said, how are we going to continue public/ private financing?

The truth is that the institutions that help fund affordable housing, whether through tax credits or Fannie Mae or some other mechanism—they are going to figure out a way to continue to make a benefit to the financial interests that have been the private part of the public/private cooperation.

There has always been a crisis in funding affordable housing. HOPE VI came out of the desperate genius of Henry Cisneros, and that program benefited a number of cities. It was viewed with skepticism when it was first proposed. A new financing vehicle will be found. If you look at the landscape of people who are funding it on the private side, these are not all bleeding heart liberals. These are people who have figured out how to make money.

However, my concern is if the President does go ahead with his tax program, we may be going backwards. In the interim between one program ending and another approach being revealed, we may not produce housing. I am going to use the President’s own logic to argue why it is good to build affordable housing. The President makes the claim that we need to improve productivity. Americans are understood to be productive workers. The untapped increase in productivity lies in the people who are joining the world of work. And you cannot be a productive worker if you don’t have a decent and stable place to live. You help the economy by helping people participate in it.

arcCA: What are some of the design innovations that we are seeing in affordable housing?

MW: The innovations that we see are ones that people who live in market-rate housing probably take for granted. New units are all being connected to the Internet. This has been very important in terms of live/work, long-distance learning and other training, small business opportunities, and helping seniors stay connected. In terms of renovating units, we try to reduce the isolation of affordable housing while maintaining security. I think you see this at Chestnut Court in Oakland and Easter Hill Village in Richmond. We try to connect the streets to the city’s grid, so the housing is connected with the larger neighborhood. Cul-de-sacs benefited the criminals more than the residents. A connected neighborhood is more easily patrolled by residents and security officers. As it gets better it can be modified. At Chestnut Court we created designs off of Grand that look like the residential neighborhood. On Grand Avenue, the design is a little more contemporary. The colors are subdued. The houses are pushed out to the street, which is the first line of defense. However, the parking is gated. Secure but visible is the idea. All of it adds up to raising the quality of design so we are not building a big arrow that says “affordable.”

Dutra Brown Building

Interview with James Brown, AIA, a partner in Public, a San Diego architecture firm. Their Dutra Brown Building in San Diego received a 2003 Merit Award.

arcCA: Where does the firm name “Public” come from?

JB: My first office was a little shed attached to an apartment house. It housed the washer and dryer. Over the years, various people used it as an office. A former tenant was a notary public, and he had a tin sign. I have always been a fan of readymade art. I collect stuff from the sides of roads, from construction sites; I’ve made a lot of furniture and art. I was trying to spell out something interesting from these letters, and I just decided to throw out the word “Notary” and keep the word “Public.

arcCA: Did you begin your practice with housing?

JB: No, with fences. I went to Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. I graduated in 1984, moved to New York, and went to work for my favorite architect in college, Peter Eisenman. I ended up in San Diego. Pretty early on, I teamed up with a friend from college, Jim Gates. We played in the same punk rock band called “The Spurts.” This was the late 1980s, and the economy was not so good. We would design gates and fences and build them. We have done more fence posts than any other architect on the west coast, on the east coast for that matter. We taught ourselves how to build, because we needed to make money. We got our first TI in the 1990s, then a house addition, and over the years we found ourselves where we are. It was incremental from $40 gate jobs—jobs that took us two weeks to do.

arcCA: What else did you build besides fences?

JB: We created a lot of art furniture and also did some public art in San Diego.

arcCA: Do you still do that?

JB: We have a wood shop and metal shop here at the office. We are licensed as architects and contractors. So we are design-build. But we don’t do that much woodwork or metalwork any more. But other folks here do.

arcCA: Do you build all your own designs?

JB: We don’t build the larger projects, like the one we are doing at UC San Diego.

arcCA: How did you move from fences to projects at UC San Diego?

JB: Our first big break after the furniture was the TI project. We thought it was pretty interesting, so I called up the photographers Hewitt/Garrison. I confessed that I didn’t have any money, but they took a gamble on us and it was published in the LA Times Magazine. David Garrison told me to go to UC San Diego and show them my work. Armed with the magazine and pictures of our fences and functional art, I set up an appointment with UCSD Campus Architect, Boone Hellman. He said this is really interesting and to keep trying. So every year, without fail, I showed him what we were doing. After ten years, we had enough of a portfolio that they hired us. But we had to compete and were selected by the users. And Hewitt/Garrison still shoots our work.

arcCA: What is the project at UC San Diego?

JB: The program includes a café with a women’s center above. Then there is another building with meeting rooms and the Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Resource Office above. On one side, there is the student center, a group of structures in a loose arrangement. On the other side is Mandeville Center, a large, rational arts complex by A. Quincy Jones. We are reinventing the “in between” space, what they call “the hump.” We are borrowing from both of the formalistic setups. We are taking a concrete plinth from the southern edge of the Mandeville project, creating a seating platform, and extending it a hundred feet. Above this element is a raised walkway that is the organizing spine for our two small buildings. The activities are more loosely organized off the spine.

arcCA: Tell me how the Dutra Brown Building came into being.

JB: Dutra is my wife’s last name and my daughter’s first name. City Centre Development, the redevelopment agency for downtown San Diego, sent out an RFP for a full city block in Little Italy. I got a call from architect/developer Ted Smith, and he suggested that a bunch of architects and developers go in together on this. There would be individual buildings by different architects and we could have a vibrant city block. We would also look over each other’s shoulders to be sure there were light and courtyards. We got the smallest parcel, and we designed it to hold four or six units. It was stipulated that one of the units be affordable.

arcCA: The design is fairly industrial looking. How did that happen?

JB: This project started in 1995, and the neighborhood has changed. Back then, Little Italy had a lot of industrial shops, and we were trying to relate to that. We wanted to use found materials. One day, I came across a goldmine. An old Navy warehouse at the foot of Broadway was closing, and I bought these two big windows that are 18 feet tall and 10 feet wide. I saved $50,000 in window costs alone. We incorporated a lot of other found materials and strange metal parts. The open living spaces face Beach Street, while the guts of the building, the circulation, bathroom, kitchen, are in the back. I wanted to make the spaces flexible so they could go between residential and office uses depending on the need.

Our building is market-rate apartments with 25% set aside for low-income. Jonathan Siegel’s project along Kettner is a market rate for sale product. Michael Gallaso and Rob Quigley designed low-income rental housing. There is the Merrimac Building, designed by Ted Smith and Lloyd Russell, and the Harbor Marine Building, designed by Robin Brisebois, which were retained. So there is a wide spectrum of design and income on this block. Instead of one monolithic project, it feels like a real city block.

arcCA: Is that a model for development?

JB: I think it should be done more often. There is an increase in administrative hassle because there are lots of cooks. I think it can work if there is one master developer leading a team of architects. This is a great model for design and for improving the quality of life. Housing people in four stories over a brightly colored parking prison is not the solution.

arcCA: Is there a downside?

JB: We helped pave the way in Little Italy, and some of the projects that followed are unfortunate. They are monolithic.

arcCA: You are also doing housing in Los Angeles?

JB: Yes, we have a project just off Santa Monica Boulevard called Lofts at Laurel Court. The developer, Avi Brosh of Palisades Development, liked the Dutra Brown Building.

arcCA: Are you drawing on Schindler at Laurel Court?

JB: I wish I could tell you that. We were trying to create great indoor/outdoor spaces. We wanted large openings and courtyards. The project contains 20 market-rate condominiums. One of our big moves was counterintuitive. At the busiest part of the site, on the corner, we chose to place a private, quiet, outdoor room behind large concrete block walls. That “hinge” allowed us to have a lot more flexibility with the rest of the site. The other outdoor space is a larger, more public courtyard, which the three residential buildings face. The exterior is beige stucco, not unlike the neighbors. The difference is that when you get to the courtyard the bright colors come out, it’s like the buildings were opened and the histories spilled out.

arcCA: Are we going to see a trend towards more medium—or high—density housing?

JB: Yes. I know there is a tremendous need for housing in San Diego and in Tijuana. Tijuana is larger than San Diego. We cannot keep traveling further and further to work.

arcCA: What is the link between building fences and these larger projects?

JB: We are able to eke out more design. We work with basic building blocks and put them together in an intelligent way. And we understand developer pro formas. We are starting to do small developments ourselves. Fences led to a table and eventually to something like the Dutra Brown Building. We are talking about incremental knowledge.

Colorado Court

Interview with Lawrence Scarpa, AIA, a partner in the Santa Monica firm Pugh + Scarpa. Pugh-Scarpa- Kodama is a partnership with Steve Kodama that created the Colorado Court housing in Santa Monica, which received a 2003 Merit Award.

arcCA: How did you get into affordable housing?

LS: We always wanted to do it, and one of our partners, Angela Brooks, had won a PA Award for her housing work. We tried very hard for many years, but it was a difficult market to get into. So in 1996 we formed a partnership with a San Francisco architect, Steve Kodama, who has 35 years experience doing housing. Pugh-Scarpa-Kodama is a separate firm that focuses on affordable housing. Kodama grew up in LA and he wanted to be more active here. We had a mutual friend who helps cities put together housing programs, and he introduced us. I think we’ve done about ten projects together.

arcCA: Do you worry about diluting or confusing the brand of your firm?

LS: People in the affordable housing sector don’t care about the brand thing.

arcCA: What was your motivation?

LS: We believe in giving something back, doing something for the greater good. We have a lot of film industry clientele. So, it’s a way to look at the other side of architecture, but I think they turn out to be one and the same. You can bring the same ideas to affordable design as to offices for movie stars. I don’t think tight budgets preclude good design.

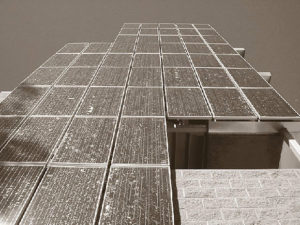

arcCA: How did you get so much sustainability into Colorado Court, an affordable housing project?

LS: We have always been interested in sustainability. Six or seven years ago, we designed the only totally solar-powered electrical vehicle charging station in the U.S., next to Santa Monica City Hall. To do that we had to be pretty creative about our strategy for funding. We found public money nobody knew about.

For Colorado Court, Santa Monica provided the land on a long-term lease and provided construction financing with the stipulation that the project would be green. However, there were no guidelines as to what that meant. We could do what we wanted as long as it didn’t cost any more. Of course it did, so we had to find the resources. Our strategy was two-pronged.

In affordable housing, there is no real resource for additional funds. In this case, they set aside a larger-than-normal project contingency. Our strategy was to design a super simple building, so simple that we would minimize potential change orders that would eat into the contingency. Every unit stacks vertically. Variety is in the horizontal elements. We used the balance of the contingency for green items at the tail-end, like natural linoleum, formaldehyde-free cabinets, paints without VOC, and recycled carpet.

The other strategy was to look for money like we did at the electric vehicle charging station. We got some money from the State through DOE in a buy-down program most people are familiar with. We also found a little known source of funding that is now called the Six Cities Program, which sets resources from utility bills aside for clean air projects.

arcCA: How did you create an “energy independent” project?

LS: A combination of tools. Solar PV panels, a micro turbine, breezeways, and cross-ventilation. The south facades have shade and the north facade has glazing. When we designed the project, we went under the assumption that we were going to make it happen. We would subtract the element if we didn’t. We were well into the process before we knew it was actually going to happen.

arcCA: With the new technology, did anything go wrong?

LS: The solar panels were by Atlantis Energy, BP Solar. They quit producing the panels we wanted, so we had to redesign the structure in the middle of construction.

arcCA: What about some of the design elements? What do they do?

LS: They are abstract patterns. It is not a machine. We don’t live in machines. Those facades are sculptural and also provide shading. We are interested in place-making, a space for people. We are not interested in making a machine that is 100 percent efficient. The key is to make a new architecture, a new paradigm. We made some sacrifices in efficiency for how people use and enjoy the building.

arcCA: Can this project become a model for affordable housing?

LS: I think it can. It’s the perfect scenario. You’ve got a building type with long-term ownership. That is how these energy strategies pay off. This is the tenant population that needs savings the most. These are the people who can least afford the utility bills. In low-income families, utility bills might represent as much as 50% of a family’s income.

We have to change the way we think. In our society, we think about the least possible amount that a project can cost in capital expenditures on day one. Not what does it cost three, five, ten years from now? These kinds of project are an investment in the future. We cannot afford not to do it. We have wars over oil. We have to look at the long-term damage of our resource consumption. Interestingly enough, the strong energy savings have proven to be a marketing edge.

The State of California has changed some of the ways they fund projects because of Colorado Court. They view environmentally friendly projects more favorably with points through tax credits. There is much you can do that costs little or nothing more. For example, using polished concrete floors is less expensive because there is no need for carpet. High content fly ash in the concrete is stronger and no more expensive. Water recycling is a minimal additional cost. Of course, the orientation of the building helps. A huge thing is to scrutinize the engineering data. My partner is an engineer and an architect, and so we questioned the engineers closely. We get them to remove some things. All of that saves money.

arcCA: What has been the reaction from the occupants?

LS: They like it. The head of the housing department in Santa Monica said, “We have done a lot of housing; this is the first one that everybody likes.” I hear that and I get a little bit worried. It must be too soft. They had 3,000 people on their waiting list for 44 units. The clients are proud that it is an environmentally sensitive bldg. They were surprised how well the tenants like the building.

arcCA: What is going to happen to affordable housing?

LS: We don’t have enough. A few years ago, I helped start a non-profit housing development corporation (www.livableplaces.org). I think well-intentioned people sometimes lose sight of their vision. Livable Places wants to influence policy. We want people with creativity and commitment to have a chance to design, even if they have not done this kind of work. We were frustrated at how affordable housing was developed and how it looked. I wanted to show that it does matter. Most affordable housing developers don’t want to do mixed-use because of how these projects are funded. We are doing mixed-use because it makes sense. So we bring together different funding sources and don’t use some of the typical sources that try and tell us how to do things. I think this group has the potential for becoming a new model for the development of affordable housing. We did this because it seemed to be the only way to make significant change in how we think about affordable housing. We’ve received almost one million dollars in grants, so someone must be listening.

Eucalyptus View Cooperative

Interview with Eric Naslund, FAIA, a partner in the San Diego firm studio e Architects. Their Eucalyptus View Cooperative in Escondido received a 2003 AIA Merit Award.

arcCA: How did your firm get involved in affordable housing?

EN: When we first started out, we did market-rate tract homes. The experience was frustrating. Very formulaic, generic, any ideas we had got shot down. We thought there has to be a better way to do this. So we entered and won a competition to design 17 affordable homes for the Redevelopment Agency of Riverside in the early ‘90s. We did things in those homes that we were telling developers they ought to do. Take technology and budgets that the for-profit world was dealing with and rearrange a kit of parts to make something else. That was what kicked it off.

We thought, this is pretty cool to do housing like this. This first project coincided with the Federal government starting to finance affordable housing with tax credits. We started working with some of the early housing organizations as they were figuring out the low-income tax credit program. We were also approached by Davids-Killory Architects, to be the architects of record for Sunrise Place and Daybreak Grove in Escondido.

arcCA: Was it your intention to design affordable housing?

EN: We didn’t have a grand plan to do affordable housing. But we wanted to do work for people who cared about the environment they were creating, people who were interested in experience, not formulas. We started to see that there are people who appreciate this, who also have a mission.

arcCA: How do you get design with these strict budgets?

EN: We embrace the problem. We don’t approach it by whining. You take what you got. What can the materials, like wood and stucco, do? We have also worked hard to set an agenda about what we are trying to do with the projects relative to better neighborhoods, quality of life, and sustainability. Those goals help us figure out how to arrange the spaces and open up the buildings. I think our skill is more in how we plan the site. When you design a good armature, it is easier to put stuff on it.

arcCA: Do you still do any for-profit housing?

EN: Because of the early for-profit work, we understood the technology and costs and where you can stretch. We have come back to the for-profit work now. We became concerned that we might get pigeon-holed into affordable housing. What happened is that potential clients saw that we could make something out of nothing and thought we could help them. We are doing a charter school that will open in the fall. Charter schools are mission-driven, like the housing. We are also doing market-rate housing in downtown San Diego and in Long Beach. Savvy developers know that the type of person who is going to rent in downtown San Diego now is looking for edgy space. They want “cool stuff” for this audience.

arcCA: Interesting that market-rate design is coming out of affordable housing. Why has San Diego become such a hotbed of innovative, medium density housing?

EN: I think it goes back to the late 1970s, when Ted Smith was building his “go-homes” in the suburbs of north San Diego County. Several residents share one kitchen—an early cohousing prototype. Ted was knowledgeable about how development works, and he pushed the envelope. Also, Rob Quigley came along in the early ‘80s, saw the old SROs going away, worked with the City of San Diego to rewrite their ordinance to allow new SRO units to be built, and then did the Baltic Inn. He went on to do a series of SROs and almost single-handedly brought back a housing type.

arcCA: Could you tell me a little about your inspiration for Eucalyptus View?

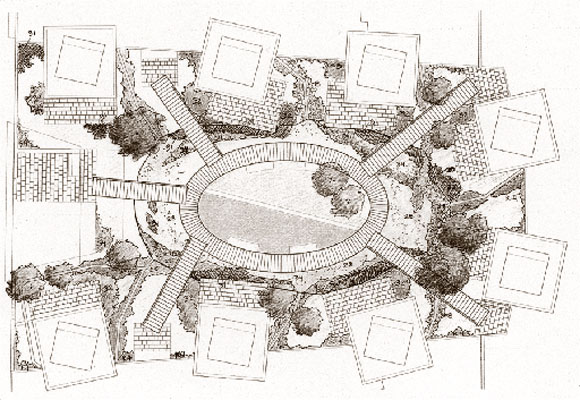

EN: We were inspired by the Southern California bungalow courts. They are a long and much loved tradition here in San Diego. There is a community space that can be shared and observed. Also, the site is located where there is a mix of commercial and residential uses. The city wanted to develop South Escondido Boulevard into a quasi-commercial area. So we placed the daycare and laundry functions along the edge of the boulevard. The residential units face the courtyard.

arcCA: What about security?

EN: There is real security and perceived security. The real security in this project is in the shared concern of the neighbors, the eyes. You mark the threshold when you come into the courtyard, so everybody recognizes a stranger. In another project we are doing in Long Beach, we are exploring a higher level of security, where the project is on a major boulevard and there may be more people up to no good.

arcCA: Can you tell me a little more about the design?

EN: We tried to have fun with the building section. We stacked units with tall living spaces displaced to create two interlocking Ls. The higher volumes and the level changes that resulted are unusual in affordable housing. Also, we don’t hide the fact that these are simple stucco boxes. But we create contrast to get more mileage out of each move. The plantings, trellises, lattice work balconies, and roofs all create interesting shadows on the broad surfaces of plaster. You can create a dialogue with small, fussy pieces and plain backgrounds.

arcCA: What kind of construction costs are we talking about?

EN: The medium-density affordable housing ranges from the low sixties to the high seventies. Market-rate would be a little more.

arcCA: With your affordable housing, have you experienced community resistance?

EN: Initially, we did. We have done a lot of work in Escondido, and every possible fear would come out. As the projects got built, people moved in, property values did not drop, and the non-profits took care of their property. The quality of the developments helped secure future approvals.

arcCA: What about the fees?

EN: We get paid a similar percentage for the affordable as the for-profit. The total fee might be a little less with affordable housing, because of the lower construction costs. What is different is when you get paid. Depending on the funding sources, it can be less frequently. Since we enjoy the work so much, it is worth it.

arcCA: What is the future for affordable housing?

EN: I have heard mixed reviews. Tax credit financing is popular on both sides of the aisle in Washington. Republicans like tax credits and Democrats feel like they have been effective. But there has been some discussion recently about the impact of the new tax bill. If you have large corporations receiving tax breaks, there is fear that it will diminish the market for purchasing tax credits.

arcCA: Do you think the medium-density housing that we see in San Diego’s Little Italy and elsewhere in San Diego is going to happen elsewhere.

EN: I think it could happen anywhere. This is not a trend that is exclusive to San Diego. What is important is integration with the rest of the city.

BoO1 “Tango” Exhibition Housing

Interview with James Mary O’Connor, a senior associate at the Santa Monica based firm Moore Ruble Yudell. Their BoO1 “Tango” Exhibition Housing in Malmo, Sweden received a 2003 Merit Award.

arcCA: How did an LA firm end up designing a 27-unit housing project in Malmo, Sweden?

JMO: We’ve been working in Malmo a long time, designing and completing a 300-unit project named Potatisakern that had won the Building of the Year award for the city the previous year. The city officials of Malmo contacted us after visiting one of our other housing projects in Germany, the Tegel Housing Project. In Sweden, there is a long tradition and a commitment for every citizen to live in good housing. They build experimental housing projects for a housing exhibition every two years. It is in a different location each time and is open for four months and features new ideas and designs. As a country, they want to explore how they should live in the future. This time around, the government invited thirty firms to participate. I think they were all Scandinavian except for our firm.

arcCA: What kind of site was it?

JMO: In this case, the government had a brownfield site, a former SAAB factory near an industrial harbor, which they were reclaiming. Swedes are ahead of us in terms of environmental consciousness and sustainability issues.

arcCA: What about China? What is the model there? A: We are working right now in a new town outside Tianjin, east of Beijing on the coast. The new town will have a population of 60,000; our project is for 10,000 units. We work with a local associate architect on the drawings. Historically, towns grow incrementally. In this project, we are doing all of those units all at once, and they want it very fast. They want the center of the project to have exclusive, expensive villas, while we are trying to explain the importance of a rich public space dominating.

We don’t want to privatize the public space. They’ve become the capitalists and we’ve become the socialists!

arcCA: But this is larger than anything you’ve done before. Why did you take it on?

JMO: This is a whole new scale. But we could affect the lives of so many people. I am amazed at the number of projects over there. Even given the scale of our work, it is a drop in the ocean.

arcCA: Who is funding your multi-family projects in Asia?

JMO: We are working with private developers in Asia. In China, the developer borrows money from the government. The clients in Asia have seen our housing projects in Europe, and they want high-income housing based on those designs for the middle class! The developers want us to replicate our European work in a very different climate and culture. The reason the European work gets noticed is that we are good at going to a place, understanding that site, and not coming up with the previous thing, even though that’s what the client often wants.

arcCA: But do you bring something of California?

JMO: Because we live in California, we do bring something different. In the Philippines, they also have those extremes of suburban and high-rise housing in the large cities. Our clients there are looking for something different. They are interested in the European model, in which you have relatively high densities with four to ten stories. They liked the sense of openness in our buildings in Sweden. I asked a German developer why he always included us on his list, and he said that we offered another alternative that is neither traditional nor ultra modern. I think the California experience of openness, of living in the landscape, of the interior and exterior informing each other is key.

arcCA: Is your firm working on large multi-family housing here in the US?

JMO: Not at the scale that we are working in Asia. Our multi-family housing reputation was built in Europe and abroad. Quality architecture in the US is not associated so much with multiunit housing, but with private homes, institutional and cultural buildings. Here, in the larger cities, most people seem to live in private suburban homes or urban high-rises. There are not much of the denser low-rise buildings—the sort of “fabric” buildings. And in Europe, most of the housing is subsidized, for middle-income as well as low-income tenants.

arcCA: Do you think we are going to see denser middle-class housing like we see in Europe or some parts of the developing world?

JMO: Yes, things are changing. We have a 60-unit project in Santa Monica. It is private sector rental housing, where the units are between 700 to 1,000 square feet. The developers here are starting to believe that there is a market for people who want to live in better-designed housing. The university clients are building better quality student housing and faculty housing. What’s happening in downtown Los Angeles is important. I think it’s interesting that some of these AIA awards are for middle-class and affordable housing.

Most of these winning projects are also experimenting with sustainable design. Certain cities, like Santa Monica and San Jose, are very committed to sustainability and a high level of design. San Jose has built a lot of good high-density housing downtown.

I also think it is important to point out that at our “Tango” housing project in Malmo, the sustainability features that seem exceptional now—how they generate more electricity than they need and sell it back, clean their own water, incorporate sustainable materials—will probably be the only way you can build in the future. It will become the norm, and we will all have to do it.

arcCA asked Kenneth Caldwell to interview architects who received 2003 AIACC Design Awards for their multi-family housing projects. All of the five projects have some element of affordable housing, ranging from a high-rise tower for the homeless to a live/work building with an affordable requirement. Although each architect approaches his work differently, all of them show us that it is possible to design affordable, multi-family housing that offers dignity and joy.

Originally published 3rd quarter 2003, in arcCA 03.3, “Done Good.”