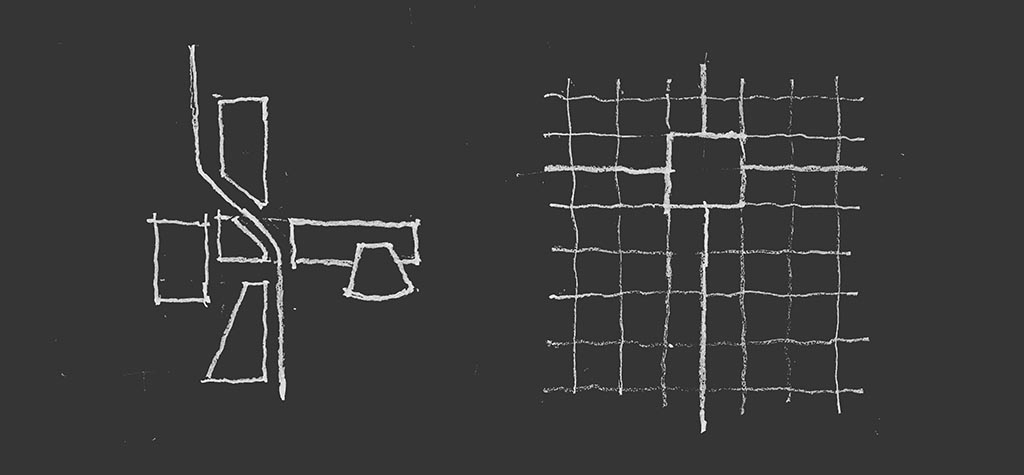

In 1978, while I was in college, I saw the historian-critic Colin Rowe speak at Rice University. He began by apologizing: his luggage had gone astray and, with it, his slide carousels, so he was going to have to manage without. He made two drawings on a blackboard, which looked something like this:

The one on the left, he said, represented the plan of a typical British new town of the 1960s, like, say, Telford; the one on the right represented the plan of Austin, Texas. His argument, as it unfolded, was that the grid of Austin was a much better way to lay out a town, because it was both ordered and easily adaptable. In contrast, the British new town, with every element tightly tailored to a particular use and the whole a precise concatenation of these idiosyncratic elements, was instantly obsolete. It was extremely hard to make changes or additions to Telford without violating its over-specified logic, whereas Austin’s grid could survive almost anything, while maintaining its dignity.

The Royal Crescent in Bath, England, offers an analogous strategy to that of Austin’s grid, but in three dimensions and at a finer scale. Built between 1767 and 1774, it was put together in an unusual way: owners purchased a length of the front façade, designed by architect John Wood the Younger, then hired their own architects to design the houses that would rise behind it. The upshot is a particularly vivid instance of a common pattern: the difference between front and back. The front of your house is what the public sees, so you put extra effort into making it proper and attractive, to contribute to the larger order of the town or city. In back, you do what is easy and convenient. There, you can make whatever changes you like, whenever you like.

Some might argue that there’s something disingenuous about the highly ordered façade of the Crescent, that it’s a skin-deep illusion. I don’t think so. To me, it’s not an illusion but a commitment, a commitment to neighborliness, to the common good. And it’s a manageable commitment, straightforward and easy to fulfill.

Forty years after I saw that lecture at Rice, I told a fellow architect about it, saying that I had been deeply impressed by Rowe’s ability to improvise. The architect said, “Hmm. That’s curious. I saw Rowe speak in Cincinnati around that time, and he’d lost his luggage then, as well.”*

*Editor’s note: It might not have been Cincinnati.

From arcCA DIGEST Season 17, “Adaptive Reuse.” The article itself has been adapted from an entry in the author’s blog, Matter and Mode.