Always contextualize. This was Reyner Banham’s golden rule in his book Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (New York: Harper & Row, 1971). Now thirty-five years old, the book should not be consigned to some antiquarian bookstore, nor smothered by respectful scrutiny or canonization. Banham discovered new ways of seeing and writing about cities that are just as vibrant and relevant in today’s urbanizing world. His was an architecture in place; he wrote a new kind of urban history, and in so doing irrevocably changed the way the world understood Los Angeles. When observers scornfully mocked L.A.’s “monotony, not unity” and “confusion rather than variety,” Banham claimed that the fault lay with them, not with the city. Their misapprehensions, he averred, resulted because the “context” had escaped them. Any perceived chaos was a product of their minds alone, for it was not something present in Los Angeles.

In place of urban chaos, Banham offered four ecologies as a way of unpacking Los Angeles. To this day, I still use his thumbnail sketches of these cardinal geographies to orient newcomers to the city:

Surfurbia (the beach cities): The beaches are what other cities should envy about L.A., Banham swooned. “Sun, sand, and surf are held to be ultimate and transcendental values,” and one way or another the beach is what “life is all about in Los Angeles.”

Foothills (the privileged enclaves of Bel Air, Beverly Hills, etc.): The foothills are where “the financial and topographical contours correspond almost exactly: the higher the ground the higher the income.” The foothill ecology comprises “narrow, tortuous residential roads serving precipitous house plots that often back up directly on unimproved wilderness even now [in] an air of deeply buried privacy.”

The Plains (the central flatlands): This is where Los Angeles is most like other cities: “an endless plain endlessly gridded with endless streets, peppered endlessly with ticky-tacky houses . . . , slashed across by endless freeways . . . , and so on . . . endlessly.”

Autopia (the freeways): The L.A. freeway system “is now a single comprehensible place, a coherent state of mind, a complete way of life” where Angelenos most feel at home. It is one of the “greater works of Man,” on a par with the streets of Sixtus V’s Baroque Rome or Haussmann’s Paris boulevards. The Santa Monica-San Diego freeway intersection is a work of art, and daily conversations about traffic are a standard rhetorical trope, much as the English constantly carp about the weather.

Writing with a characteristic grace and wit that even his most pungent critics were obliged to concede, Banham’s four-part ecological symphony was constantly interrupted by dissonant improvisations on urban and architectural history. These chapters included riffs on fantasy architecture and architects-in-exile, as well as a brief note on downtown L.A. (because, he claimed, “that is all [it] deserves.”) The text’s non-linearity upset many readers, but Banham clearly intended it as a deliberate metaphor for the fragmented and discontinuous nature of the L.A. urban experience.

I was a graduate student in University College London when Banham taught there. This was at the tail-end of the “Swinging Sixties,” when self-absorption and extravagance were at a premium. It was (supposedly) all happening in London at that time: Twiggy, Carnaby Street, Archigram, and all that. Yet Banham appeared to turn away from it all. Instead, he wrote in hallowed terms of what others regarded as the armpit of urban America. His overheated brain celebrated L.A. surfboards, automobiles, and even hamburgers as works of art. But he was not being inconsistent or obtusely contrarian. In London, Banham had been engrossed in Pop Art, and through it he found easy entry into Los Angeles. He regarded L.A. as urban art, an honorific he wittily extended to Las Vegas, “which takes some of the established trends in the Los Angeles townscape and pushes them to extremes where they begin to become art, or poetry, or psychiatry.”1

Everything Banham wrote still seems fresh, but what would this forensic urbanist make of contemporary Los Angeles? He would probably be most taken aback by downtown L.A., which has experienced several building booms since 1971. Downtown L.A. now even looks like a conventional downtown: a cluster of high-rise office towers, some starchitect-designed civic and cultural buildings, sports venues, top restaurants, and burgeoning residential neighborhoods. Yet it still remains only one out of many Southern California “downtowns,” and I suspect Banham would agree that the best thing to do with Bunker Hill is to put a fence around it and to charge admission.

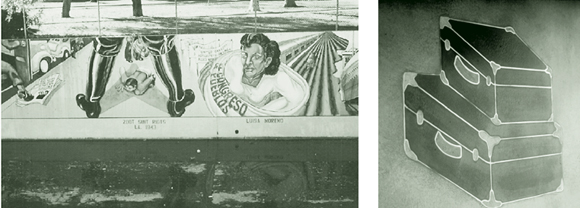

Always driving, rarely a flâneur afoot, Banham would be unmoved by the proliferation of pedestrian-oriented shopping malls, seemingly so essential to today’s urban experience. He would feel less warmly toward those “psychotic forms of territorial possession” that we call “gated communities.” But he would be genuinely delighted by L.A.’s resurgent sense of history, most evident at the grass-roots level in (for example) the murals of the Great Wall of L.A., or the Power of Place projects in Little Tokyo commemorating the World War II internment of Japanese-Americans, or Biddy Mason Park. These are much more democratic forms of remembering than conventional forms of public memorializing, which in any case remain rather rare commodities in L.A. I believe Banham would cherish these small spaces as something completely consistent with L.A.’s cartography of diverse, fragmented memory.

The sheer size of contemporary Los Angeles would likely leave Banham speechless, if only momentarily. The five-county metropolitan region (incorporating the counties of Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, and Ventura) is today home to more than sixteen million people, twice what it was in Banham’s locust days only thirty-five years ago. It comprises 177 cities spread over 14,000 square miles. It is an emergent world city, molded by an urban dynamics that Banham could not possibly have imagined. His immediate reaction to L.A.’s demographic diversity might simply be annoyance that his 1971 book could so underplay race, immigration, and gender issues. But then he would remind himself: Always contextualize! What are the forces that today determine L.A.’s efflorescent urban ecologies? In my judgment, five matter more than most:

- Globalization, the rise of an integrated global economy characterized by the emergence of a closely linked hierarchy of world cities that act as centers of command and control;

- Network society, the transformations wrought by the arrival of the “Information Age,” including a global media connectivity;

- Social polarization, the ever-increasing socioeconomic divide between the very rich and the rest of us;

- Hybridization, the mixing of racial and ethnic groups and traditions brought about by the shrinking of distance, an ubiquitous media, and large-scale domestic and international migrations; and

- Sustainability, the emergence of a global consciousness regarding the finitude of resources, habitat, flora, and fauna, plus the consequent threat to planetary survival.

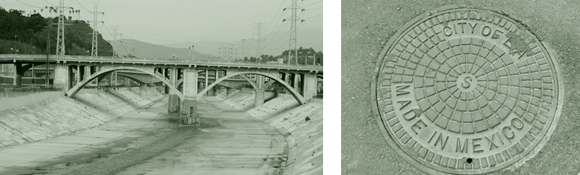

These five tendencies—globalization, network society, polarization, hybridization, and sustainability—are common in the landscapes of Southern California. In the “wild east” around Ontario, for instance, vast acreages of distribution centers house and move the goods that arrive at the nation’s largest port complex (Los Angeles-Long Beach). In West L.A. and the Valley, names like Sony, Yahoo!, and MTV attest to L.A.’s role in a globalized media society. The landscapes of poverty are everywhere; in downtown L.A., for example, the region’s largest concentration of emergency shelters for homeless people emerged during the mid-1980s. The rise of “ethnoburbs” in the San Gabriel Valley testifies to the arrival of affluent Chinese immigrants who take up immediate residence in well-to-do suburbs, bypassing the traditional immigrant experience of inner-city Chinatown. Finally, the Los Angeles River was a forgotten, channelized, concrete gulch until the Friends of the L.A. River (FOLAR) began to make the river a centerpiece in a revitalized region-wide environmental consciousness.

Banham taught us to see Los Angeles differently, but he made no large claims about the wider lessons of L.A. for other cites at home or abroad. He remained wedded to the notion of L.A.’s uniqueness, and yet his book contains the seeds of a more general urban theory whose potential is only now being realized. At the core of Banham’s putative revisionism was the observation that L.A. “has no urban form at all in the commonly accepted sense” of an “outward sprawl from a central nucleus.” For him, downtown L.A. would never qualify as the heart of the city, partly because Wilshire Boulevard already existed as a “linear downtown.” The problem, in Banham’s view, was that observers of L.A. had once again got it wrong; they were forcing the city “into categories of judgment that simply do not apply.” What we are in fact looking at in L.A. is an agglomeration of suburbs without a single center, an arrangement that profoundly contradicts existing conventions in urban theory.

Although Banham himself did nothing to develop the implications of these observations, the revolutionary potential of his L.A. road trips was recognized by Tony Vidler in his introduction to the 2001 reissue of Banham’s book. Vidler observed that Los Angeles provided a “tightly constructed part manifesto, part new urban geography.”2 For myself, looking back over two decades of research and practice in L.A., only now do I appreciate the extent to which I absorbed the insights of Reyner Banham’s Los Angeles—though with consequences totally different from Vidler’s.

My involvement in the emergence of the “Los Angeles School” of urbanism is profoundly rooted in Banham; so is my approach to “postmodern urbanism”—whose core conviction is that contemporary urbanism no longer follows a modernist core-to-hinterland logic, but instead insists on a postmodern conceit in which the hinterlands organize what remains of the urban center.3

Any revitalized urban theory, in which urban peripheries dominate what is left of the core, will require a new language for describing urban growth and change. For example, in many cities it no longer makes sense to speak of “suburbanization,” understood as a peripheral accretion to a center-dominated urban process; edge cities may look like suburbs, but they are not. Neither can “ethnoburbs” be equated with traditional concepts of immigrant ghettoes, as I have already explained. New ways of seeing cities will also require a fresh approach to making urban places. For instance, it seems hopelessly naïve to assume that an urban policy for downtown renewal can restore vitality to a city center that has been bypassed by a non-core-oriented urban process.

Reyner Banham loved L.A. because it was (and is) a place permeated by a palpable “sense of possibilities still ahead.” He understood that L.A. “threatens… because it breaks the rules” of conventional theory, practice, and pedagogy. Thirty-five years after Los Angeles, Banham would still get a kick out of L.A. He would extend his ecologies to include the San Diego-Tijuana borderlands and the miles of fencing today separating the U.S. from Mexico. He would revel in the mestizaje urbanism of L.A.’s phenomenal diversity. He would drive every corner of the Inland Empire and find a prominent place for the desert in his urban ecology. He would be amazed by the variety and geographical reach of Southern California’s artistic, intellectual, and cultural scenes. He would grieve over L.A.’s status as the homeless capital of the USA. And he might even agree that L.A. has altered the ways we understand cities everywhere.

- Banham, “Las Vegas,” Los Angeles Times, West Magazine, November 8, 1970, pp. 38-9.

- Anthony Vidler, “Introduction—Los Angeles: City of the Immediate Future” in Reyner Banham, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), p. xxxi.

- An introduction to the precepts and concerns of the L.A. School is to be found in Michael Dear (ed.) From Chicago to L.A.: Making Sense of Urban Theory (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2002); see also Allen J. Scott and Edward W. Soja (eds.) The City: Los Angeles and Urban Theory at the End of the Twentieth Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996). My personal view of the L.A. urban problematic is found in: Michael Dear, The Postmodern Urban Condition (Wiley-Blackwell, 2000).

Author Michael Dear is Professor and Chair of the Department of Geography at the University of Southern California and Honorary Professor at the Bartlett School of Planning at University College London.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2006 in arcCA 06.2, “L.A.”