The artist Robert Smithson once described the natural phenomenon of entropy in the following manner: imagine a child running between two sand boxes, one with white sand and the other with black sand. As the child continues to run in a clockwise direction between the two, the sand increasingly mixes into a uniform gray. He is then told to run in a counter-clockwise direction, though one discovers that this will not undo the previous mixing and re-sort the colors. Given an infinite amount of time the sand could never reorganize — the process of entropy will irreversibly continue.1

A similar observation can be made regarding the physical and social interactions that shape the ongoing saga of the Salton Sea, a 40-mile stretch of inland salt water in the Southern California desert, east of San Diego and 30 miles north of the Mexican border. Accessible by car, it is a surreal index of a sea created by an artificial canal gone awry, vacation communities stopped dead in their tracks, and water so toxic as to create coastal sands made entirely from bones. Mistakenly, the sea appears to be a life- giving oasis (a mirage?) within its arid and rocky setting, and is a mere thirty-minute drive from the super-irrigated green golfing lawns of Palm Springs (a constructed mirage, to be sure). The Salton Sea is out of control in an entropic interplay between organic forces and artificial interventions.

Accidental Rupture

As the Baja California peninsula began its Miocene shift away from the continental mainland, the Golfo de California and the Salton Trough were formed. Formerly part of the gulf sea, the dry trough sank further into the earth, creating the Salton Sink, an isolated depression of land hundreds of feet below sea level.

Fast-forward to 1905, when a man-made irrigation canal, built to divert fresh water from the Colorado River to agriculture in the Imperial Valley, abruptly broke its levees due to an unanticipated overflow of storm water. Through this catastrophic rupture, the entire irrigation flow from the Colorado River spilled into the Salton Sink, force-filling it with fresh water.2 In due time, the levee was successfully dammed (reportedly using scores of discarded railroad cars as filler), but the Salton Sink had become a permanent body of water, renamed the Salton Sea. Adding further distinction to this new aquatic feature, the Salton Sea’s water elevation is 236 feet below sea level, putting it in the same “low” class as the Caspian and Dead Seas.

During the 1950s and ‘60s, the Salton Sea was vibrantly promoted as a vacation oasis within this desert where summer temperatures routinely reach above 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Situated between the aptly named Chocolate Mountains (home to the military’s Chocolate Mountain Impact Area and off limits to civilians due to live aerial bombing) to the east and Anza Borrego State Park to the west, the sea offered stunning views and a bounty of affordable seaside land. The water was stocked to attract sport fishing, and the sea was advertised as a boating and water-skiing paradise. The sea’s coast sprouted speculative communities, the largest being Salton City on the western shore. Names like Mecca Beach, Oasis, and Slab City were sure to attract the curiosity of newcomers, and areas like Bombay Beach (rumored to have been named after a bomb was dropped, creating a small bay) were established as year-round trailer park living environments within the unforgiving landscape. Perhaps in the ultimate spirit of optimism, architect Albert Frey (a longtime resident of Palm Springs who designed experimental desert structures alongside Richard Neutra, John Lautner, and Donald Wexler’s all-metal housing), completed the North Shore Yacht Club in 1959, adding a central pulse to the sea’s newfound existence.

Tainted Waters

The topographical qualities that gave birth to the sea were also indirectly threatening its longevity as an asset in the otherwise harsh environment. Lacking any natural source of replenishment other than run- off from sporadic local precipitation, the sea most likely would have dried up, returning to its original, arid state. As it turns out, however, increased agricultural activity in the hyper-productive Imperial Valley region has brought steady irrigation runoff, flowing downhill into the low level sea and guaranteeing an abundant supply for the recreational waters.

Unfortunately, this “nourishment” has come with a paradox: the irrigation water is heavily laced with herbicides, pesticides, and additional topsoil salts, which exacerbate the already high salinity caused by mineral salts seeping from the sea floor. The result over time has been catastrophic to the marine and recreational life of the Salton Sea, with fish and bird-life dying off in debilitating numbers and visitors flocking elsewhere.

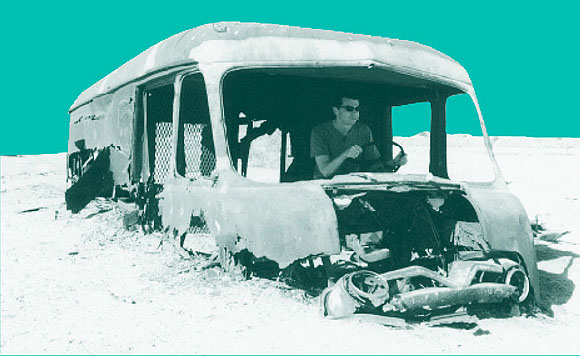

Along with the rise in contamination, the water level itself has continued to rise with the increased agricultural development, creating permanently flooded communities and forcing many remaining residents to flee. Not to be defeated, the Bombay Beach community constructed earthen dikes between its village and the sea, with sump pumps strategically placed to guarantee dry land for its occupants. Presently, it rests approximately 10 feet below the water level, and visitors find themselves driving up to the beach. Half-submerged mobile trailers and cars litter the coast, and telephone and power line poles march perpendicularly out to sea, indexing underwater roads. A road map of the region still touts the Salton Sea as a vacation haven, yet warns water enthusiasts (those brave enough to enter this murky fluid) to be aware of such underwater obstacles as trees, structures, and automobiles when boating or water skiing.

The panoramic beauty of the sea provides a contradictory façade to what lies beneath. Enormous algae blooms have voraciously multiplied, sucking available oxygen from the water and killing fish strong enough to survive the rising pollution and salt levels. A walk along the water’s edge provides a curious yet startling realization: the aggregate crunching beneath one’s feet in many places is not sand, but the crushed ribs, spines, and scales of dead fish — an animal sand. Many more fish float lifeless in the water. A rank, pervasive stench rises from the water and lingers in the air.

Emblematic of the convoluted relationship between nature and the man-made, the Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge and the Salton Sea Military Test Base approach within a mile of one another at the sea’s southern end.

Zone

In Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 film, Stalker, a small group of truth seekers ventures into the “zone,” an area of wasteland surrounding the ruins of a nuclear power plant. Though spoiled by its past, the land- scape is rumored to contain hidden forces worth seeking and protecting, and thus its torment creates its attraction. The visitor to the Salton Sea region confronts the same enigmatic presence. The sea’s crises, though serious and many, have nevertheless intensified this area into one of the most provocative landscapes in California.

Further layers complete the picture: the San Andreas Fault lies directly under the Salton Sea’s eastern shore; its northern vicinity is one of the windiest places in the country and home of the Tehachapi Valley Windmill Farm, the second largest windmill cluster in the world. Nearby Slab City, surprisingly designated on a regional map, is a nomadic “non-city” where residents park their mobile homes on concrete slabs that are the residue of military buildings long since demolished. Marking the entrance to this surreal desert conglomerate is Salvation Mountain, providing a colorful beacon amidst the beige desert sands. It is the creation of a desert eccentric, who for years has been painting an entire hillside with a concoction of house paint, mud, and straw in dedication to the afterlife.

Today, Albert Frey’s yacht club stoically stands, boarded shut, its outdoor pool and walkways cracked and contorted. Undeterred visitors and high- way nomads stop to inspect this once hopeful relic and to gaze upon its silent land and seascape. Across the water, Salton City lies poised for a future that has not yet arrived: most of its infrastructure of roads, sidewalks, and street lights remains empty and silent at water’s edge, awaiting new occupants who surely will never come. Robert Smithson created an active exchange between artificial and organic forces with his “Spiral Jetty” earthwork in Utah. Visitors to the Salton Sea are treated to the same entropic interplay, but on an extreme scale. It is high-speed geography, appearing to change between every visit.

Notes

1. As discussed by Rosalind Krauss in Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind E. Krauss, Formless, A User’s Guide (New York: Zone Books, 1997), pg. 73. From Robert Smithson, “A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey,” Artforum, December, 1967.

2. Center for Land Use Interpretation, 2000.

Author Thom Faulders is the founder of FAULDERS STUDIO and Professor of Architecture at California College of the Arts in San Francisco. Opening photo by the author.

Originally published 4th quarter 2001, in arcCA 01.4, “H2O CA.”