Driving west down Oakland’s High Street on a fall afternoon—with the setting sun blinding you as you weave between cars turning left and cars parked on the right—can be a stressful experience. Pinned at both ends by congested Bay Area freeways, High Street is too narrow for the speed that drivers insist on when they strategically shift from one freeway to the other to avoid traffic. One of the left turns is to Courtland Avenue. Here, the drop in elevation and a row of purple-leaf plum trees announce a space qualitatively different from the hectic world you just escaped.

Ten years ago, when I first visited this neighborhood, I would have driven past that turn without registering the slightest interest. A five-block swath of vacant land was all that remained of the Courtland Avenue streetcar line that used to carry workers from downtown Oakland or the San Francisco ferry to their homes in East Oakland. That line was abandoned about thirty years ago, and over time the right-of-way acquired its own character as a place to repair cars, hang out, secretly dump garbage or even grow a vegetable garden. Some sections of the right-of-way pro- vide access to modest homes, but in other areas Courtland Creek, running parallel to the right-of-way, reveals an untamed urban wilderness of exotic and native plants within its deeply incised channel.

When the idea of transforming the right-of- way into a park started to be discussed in 1990, many people—neighbors, designers, city officials and others—envisioned primarily a visual improvement to the neighborhood. The park, however, does more than replace dirt with grass. It claims a piece of the public domain as a community resource that expresses its locality and begins to address some of the unmet environmental, recreational and social needs of the local residents. The park enhances the life of the community, both through the social inter- action essential to its creation—the seven-year process of design and implementation brought together neighbors, city officials and activists—and through the physical provision of space.

The project was not without impediments. An existing recreational facility across High Street, even though it is difficult to reach on account of traffic, could have discouraged city officials and neighbors from creating a new park on the vacant land. Logistical factors such as sections in private ownership and access requirements might have impeded the project as well. Furthermore, community conditions did not assure its success even if built. The neighborhood was caught up in many of the problems that low-income communities face. Advocates had to address their own concerns that, by creating a park to enhance positive uses, they might also facilitate existing negative uses like drug sales and loitering.

Opportunities arose, though, that made the venture successful. The presence of a creek along the corridor captured the attention of a non-profit advocacy group, which then received grant funding to restore sections of the creek. In turn, this group secured the imagination and resources of Walter Hood, now chair of landscape architecture at the University of California, Berkeley. Through a com- munity design studio, he and his students collected historical information, conducted interviews, held workshops, led exploratory walks and developed a master plan for the site. His firm, Hood Design, then developed a specific site design based on the master plan. A core group of neighbors tenaciously stuck by the project for the seven years it took to make the park a reality. This group represented a larger neighborhood context and included uphill neighbors who had professional and activist experience in “working the city.” Throughout the slow process from idea to implementation, the collaboration of community members, city agencies, non- profit organizations, university affiliates and Hood Design provided the requisite energy to see the project through to completion.

While the participatory design process was a strong basis for enhancing community, perhaps more crucial was how this process led to a particular physical manifestation of street and park. Long after the ribbon-cutting ceremony, a park has to perform its role as a community space. What follows is an analysis of the physical features of the park: contextual considerations, program elements reflecting community use and details that reinforce community expression.

Designing within Context: Topography and Street

Before the area was developed, Courtland Creek would have been the low point between two hills on its course to San Francisco Bay. With urbanization, the imposition of the street grid required manipulating the topography into a series of slopes and flattened spaces. Courtland Avenue cuts across a hill that once sloped down to the creek. Spanning from linear street to an undercut creek, Courtland Creek Park has to address two very different contextual conditions. Along the five-block length of park, the south side of the street is lined with modest homes slightly elevated from the street. On the north side, new curbs and gutters create a clean edge where gravel once merged street and right-of-way. Topographic slack is taken up in the old right-of-way, producing some interesting conditions that the park’s design exploits for maxi- mum effect. Where the park is level with the street, it expands the street’s visual plane, especially where the creek opens up views of vegetation on the far bank. Steps down to the creek invite a whole new experience of a riparian corridor visually removed from the street. At other level sections of the park, where the creek has been culverted and the right-of-way pro- vides access to homes, the site is paved to support neighborhood functions such as parking and children’s play. In another section, a change in grade requires that one part of the park be separated from the street by a ten-foot retaining wall. Here, a long- time resident continues to plant his vegetable garden, and his collard greens and corn, always beautiful, are now legitimized as a public amenity.

A Program Reflecting Community

Even before the park was built, the right-of-way had a life of its own that reflected community use patterns. It was important that the proposed design not remove existing uses but enhance them. To do so required that Hood Design reinterpret activities ranging from the illegal to the simply inappropriate—drug dealing to car repair—into acceptable forms. For example, rather than ignore the fact that youth hang out in the park, several spaces were created that identify the site as a suitable place to meet. One prominent corner is marked by a folly that not only provides interpretation of the site’s history via maps incised on its columns, but also celebrates the corner as a social space.

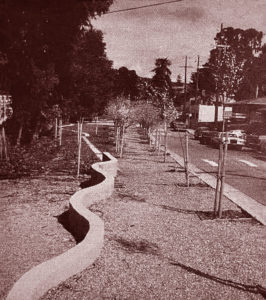

The linearity of the park and its function as a corridor for circulation inspired the creation of a promenade along the street edge. Instead of a typical sidewalk, an allée of purple-leaf plums on a decomposed granite path forms the boundary. From this spine, various park functions are organized into bands. Children’s activities are interspersed along the corridor, which includes hard-paved surfaces for ball games, a peewee basketball court and a sand yard. In three areas where the park extends to the creek, lawns provide space for field games, dog play and neighborhood parties. At the east, where Courtland Avenue dead-ends to make room for a wider creek corridor and the right-of-way, the park becomes a piece of urban wilderness, a bit scary but wonder- fully adventuresome. Though restoration purists would like to do away with all the non-native species, wholesale removal has been avoided in order to retain the wild sense of the space.

Advocacy Detailing

Given a modest budget, the designer’s challenge was for each intervention to have maximum effect. With a palette of concrete (for walls and seats), plants and donated decomposed granite, the design uses juxtaposition, allusion and multifunctional elements to reinforce site and program. The resulting design illuminates anew the landscape and reveals its environ- mental and social history. For example, the allée of purple-leaf plum trees, a circle of redwoods and other formal geometries in the planting plan contrast with the creek’s vegetation and the eclecticism of neighbors’ yards. This juxtaposition is reinforced by a one-foot concrete path marking the edge between the riparian corridor and lawn. The promenade expresses the park’s presence through its dense planting (fifteen feet on center rather than the standard of thirty to fifty feet) and by plant selection that changes with the seasons from bare trees to pale pink clouds of blossoms to red-leaf massing. Hybrid site objects— retaining walls that allow for garden terraces, seat walls that allude to the creek’s meander, planting edges that serve as narrow paths—support activities while also providing design cohesion. Bollards placed to discourage dumping and parking in some of the areas also act as seats, conveniently located on corners where people are accustomed to meet. The history of the site as a creek and streetcar corridor is marked by curving bench walls and hard edges that separate the maintained and wild planting areas.

Courtland Creek Park—whose success will be measured by its continued adaptability and use— decisively illustrates how an underutilized public space can become a community resource. It also demonstrates that the medium of landscape can illuminate environmental and social context. Through the design process the park has greatly expanded its potential: responding to existing environmental and social conditions, the design expresses the unique characteristics of the community.

Author Laura Lawson is an assistant professor in the School of Landscape Architecture at Louisiana State University. She received her PhD in Environmental Planning from the University of California at Berkeley. Her research explores how the landscape can be a resource for community empowerment through process and design.

Photos by the author.

Originally published late 2000, in arcCA 00.2, “Common Ground.”