The school day for most students revolves around the rituals of reporting to class, studying, taking tests, playing sports, and interacting in a variety of campus settings. In southern California, the majority of schools have traditionally been located immediately in or near residential subdivisions, taking advantage of the availability of open space for sports fields, close access to students’ homes, and isolation from perceived dangers posed by the city. Although schools do exist in a number of California urban settings, seclusion from the city rather than assimilation into it has often characterized the approach to school location.

In contrast to this tendency, two of this year’s AIACC Design Awards winners, along with their clients, undertook efforts to design new schools located in relatively dense commercial areas. One of the two projects, Santa Ana’s Mendez Fundamental Intermediate School (designed by LPA, Inc./Francis + Anderson), is located immediately adjacent to a large retail complex and incorporates a mixed use—a parking lot below its main building mass—to serve adjacent stores. The other school, Santa Monica’s Wildwood School (designed by SPF Architects), is located on busy Olympic Boulevard in a light industrial/office district, in a renovated brick industrial building. While the two serve distinct constituencies, they respond to multiple—and sometimes contradictory—pressures presented by their urban situations.

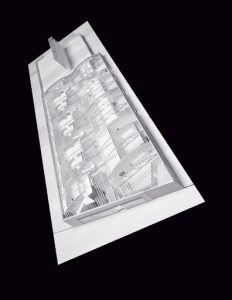

The first of these two projects, the Gonzalo & Felicitas Mendez Fundamental Intermediate School, reflects modernism’s fascination with nautical imagery in the design of a new facility for 1300 students. Spatially, the project’s elevated plazas and promenades offer vistas that are high and dramatic, subtly recalling the experience of standing upon the deck of a grand ocean liner. The material disposition favors crisp edges and clean surfaces rendered in white plaster and concrete, architectonic devices such as billboard-like translucent screens and shading canopies, and an elongated main building mass. Students experience much of school life upon this raised structure, which threads itself along the surprisingly narrow site. The composition of terraced building forms and densely arranged site plan creates an ordered hierarchy and extensive, although mostly hardscaped, outdoor spaces.

The nautical metaphor was natural for a design team that admired modernity’s grand vessels, although this understates how aptly that metaphor is matched to the school’s site constraints. Perhaps the design team’s most astute choice was raising—and isolating—the main levels of the school from the ground. While this might be an unexpected strategy in a conventional setting, the school’s location next to a series of “big-box” retail stores made it a necessity. The choice of this location was predicated on the use of funding from a special program for “space-saver” schools, which requires integration of mixed uses; the retail parking on the building’s lowest level fulfills the mixed use requirement. This program allowed acquisition of a smaller site than would normally be approved, while providing funding equivalent to that of a full-sized school. Considering the unusual context—a narrow site and the necessity to isolate such outside parking uses from student activity—the school’s elevation from the ground plane appears to be a perfect solution. Like other majestic liners, the school floats elegantly over the sea, although in this case it is a sea of cars.

Reflecting careful planning, the school grounds remain surprisingly secure from the adjacent retail area. Access is limited to a single entry court, contained by the walled edge of a residential neighborhood, utilizing the main building mass as a buffer. The playfield acreage is smaller than normal for a school of its population, but it is still ample and offers close and secure access to the main buildings. The flexible layout of clustered classrooms is comfortably linked to a common room. Meanwhile, the well-appointed library affords the visual play of a punctured “light wall” as the backdrop to individual study or group gatherings. Such destinations and the thought devoted to their layout help to create an educational environment that is both pleasant and appropriate to its mission.

Like the Mendez Fundamental School, the private Wildwood School is the product of space and economic limitations, as well as its specific urban context. As an adaptive reuse project, the school shares its Santa Monica block with a surprisingly active group of businesses, including a home furnishings store (with its loading dock), a mid-rise office building, a restaurant, and a gas station. The school has previously offered only classes below the high school level; the present project creates an additional campus capable of absorbing graduates from its existing facility. The school welcomed the opportunity to inhabit an urban location in support of its mission to involve students with their community.

The project’s material choices and spatial organization within a former industrial building convey a remarkable sense of exuberance and freshness, especially when one grasps the limits imposed by the project schedule and budget. The designers, SPF Architects, began their involvement with the project a mere five months before the scheduled first day of classes. The conversion of the 40,000 square foot existing space to a 420 student, 55,000 square foot school required the imposition of a radically accelerated schedule; in response, the team shrewdly organized the project in three phases to coincide with the arrival of each successive matriculating class. The project pushed the firm to “stretch its limits,” partners Jeffrey Stenfors, AIA, and Zoltan Pali, AIA, explain. “It showed us what you are capable of doing in a very short time, if the ideas are sound. We went through a lot of quick gyrations.” While the strategy required students and teachers to live with some dust, it seems worth the inconvenience. The completed design uses an attractive palette of low cost materials and expresses a vision well suited to the Wildwood School’s alternative education model.

The lack of outdoor recreational space available on the site—students are currently transported to nearby facilities for sports activity—highlighted the need for appealing internal spaces. The most important of these is a boulevard-like passage that runs the full length of the building and serves as the primary link between four ‘learning pods,’ or multidisciplinary classrooms, and the main performance stage and music room. The pavilion-like ‘pods’ are independent of the main roof and help set the tone of a playful academic village. The open volume above highlights the many exposed ceiling elements. Existing bowstring trusses, structurally reinforced with glu-lam beams and steel connectors, electrical conduits, and sundry mechanical innards are carefully organized. The addition of acrylic lids on the lower ‘pods’ ingeniously exploits ambient natural light from newly-installed skylights, bringing a pleasant sense of street-ness to the main floor. The designers’ willingness to expose the existing brick, concrete, and wood and the new clear-coated plywood surfaces—a familiar but still-compelling strategy of loft renovators—highlight the building’s own history and lend a vibrant, studio-like quality to the space.

As playful as all this seems, SPF’s partners emphasize that rationality and clarity of purpose guided the design process. The dimension between the trusses, for instance, was thoughtfully matched to the ideal classroom size, and the light tones of wood, metalwork, and paint all help boost available illumination. The performance spaces are carefully positioned to allow control by a public reception desk and permit isolation from the classroom pods. The care in addressing these pragmatic issues preserves the design’s playfully liberating, freeform ambiance; it also reminds one that education is ultimately about discovery and stimulation.

The success of these two award-winning designs serves to highlight the complexities of creating safe, pleasant, and effective schools in busy, nonresidential locations. The projects also emphasize the fact that urban schools—and the conditions that create them—are challenging school design conventions. One of the most visible challenges is a questioning of the notion that schools are timeless institutions whose materials will last for the long haul. The budgets associated with both of these projects seem to dictate the use of lower cost materials, perhaps indicating changing administrative attitudes or funding circumstance. The Mendez School, for instance, is built of plaster rather than more traditional materials such as brick or stone; no doubt this choice was made out of budgetary necessity. Even more dramatic is the Wildwood School’s decision to create its studio-like loft through tenant improvements to a former industrial building. One could imagine that, as time goes on, this second approach would allow for easy, cost efficient modification. Both of the institutions tacitly acknowledge that impermanence is a necessary, if involuntary, reality for modern school projects. Nevertheless, both design teams succeeded in creating dramatic and stimulating environments despite limited resources.

A second challenge is posed by the reduced open space available for playfields in urban settings. Not surprisingly, both schools have developed specific strategies to deal with this dilemma. Of the two projects, the Mendez School’s playfields offer the most generous outdoor space. Yet the school’s most successful design feature—the building’s elevation onto its own plinth—also increases the difficulty of adding landscaping to its promenades. Still, those promenades contribute to an airy sense of openness, which is desirable as an escape from the rigors of the classroom. In contrast, the Wildwood School pragmatically transports its students to off-campus recreational facilities (although it is also currently studying the addition of limited landscaping to the roof of its own parking garage). Its ultimate architectural solution relies on the creation of an attractive indoor street. As different as these strategies are, both respond to their site particularities and offer creative, effective solutions.

A final challenge is the need to rethink security strategies as schools move away from more isolated and protected suburban sites. The defining question is how schools can strike a balance between hopes for community/student interaction and realistic controls on public access. In the Mendez School, a community room is available to the public, but it is only accessible near the school’s secured main entry. Similarly, the Wildwood School’s performance spaces are accessible via the controlled reception area near the front entry. The Mendez School is the more restrictive of the two, limiting access to a single entry point, which provides a reminder of the special security needs of an intermediate school. With one-quarter the student population, the Wildwood School utilizes two controlled entries, although the school also provides security staff at the main entry.

The result of these thoughtful design strategies is that both schools enjoy the embrace of their urban surroundings. While some of the Mendez School’s retail neighbors have departed due to a slowing economy, its community room remains available for use by local residents. Likewise, the Wildwood School plans to engage its neighbors fully, providing accessible performances and encouraging students to undertake projects in the community. While the latter approach is more appropriate for high school than intermediate level students, both school designs underscore the rich possibilities inherent in rejecting a policy of academic segregation from everyday urban life. In this regard, both projects can serve as a bellwether for the next generation of urban schools.

Project Credits

Gonzalo & Felicitas Mendez Fundamental Intermediate School

Irvine, CA

LPA, Inc. (Design Architect); Jim Kisel, AIA, Project Principal; Glenn Carels, AIA, Principal in Charge of Design; Steve Flanagan, AIA, Project Designer

Francis + Anderson (Architect of Record); Chris Francis and Andy Anderson, Principals

Wildwood Secondary School

Santa Monica, CA

SPF Architects: Jeffrey Stenfors, AIA, & Zoltan Pali, AIA, Principals-in-Charge; Judith Fekete, Assoc. AIA, Principal; Dan Benjamin, AIA, Project Manager; Siddhartha Majumdar, Job Captain; Gregory Fischer, Frank Lopez, Damon Surfas, Shaheen Seth

Author David Thurman is a Senior Associate at Barton Myers Associates.

Originally published 4th quarter 2002, in arcCA 02.4, “New Material.”