The very qualities that make the best Modern buildings and landscapes worth preserving are also those that make the process challenging and the outcome sometimes less than satisfactory. Tremendous transparency, a minimalist approach to detailing, experimental technologies, and program- driven design define some of the best modern architecture, but these concepts are often the ones most affected by changing use, concerns about security and access, new technologies, code requirements, and social patterns. While the Modern period includes a very diverse body of work by those practicing in many regions and over a long span of time, an understanding of these identifiable themes must be integrated into the restoration, rehabilitation, or adaptive reuse of almost any Modern building. A closer look at the fate of two significant and innovative buildings from the mid-1950s highlights these specific challenges and illustrates varying approaches by architects and owners in dealing with the legacy of important Modern buildings.

Blurring the boundaries between inside and outside through transparency, the use of extensive glazing, and carrying similar materials and details from the inside to the outside were seen by architects such as Mies van der Rohe and Paul Rudolph as ways to design for a modern lifestyle that embraced informality, a greater connection to the outdoors, and a more democratic approach to institutional buildings. Solid and imposing masonry edifices no longer conveyed the appropriate message for civic buildings, which instead were designed to be open and transparent. Maintaining this transparency and openness in a society obsessed with security and worried about energy costs is not easily solved without a real commitment to a preservation ethic and an appreciation for the design intent.

Crown Hall

Mies van der Rohe’s Crown Hall in Chicago, completed in 1956 to serve as the IIT School of Architecture, is one of the iconic buildings of the Modern Movement. A large, long-span, glazed pavilion hovering over the ground plane, its structural elements are its main defining features. Over the years, its appearance and condition have suffered due to poor maintenance, as well as Mies’s use of many experimental technologies—he pushed the envelope of tolerances in order to achieve the greatest effect from the fewest, smallest, and thinnest members.

When IIT, with preservation architects Gunny Harboe and architects Krueck and Sexton, undertook a comprehensive restoration of the building in 2005, the rehabilitation of many architectural elements, which in any other building would not seem so important, required intense and careful scrutiny. Mies had used 1/4″ glass for the building’s enormous windows, many of which had broken over the years, and the remaining panes moved in the wind. Current codes require much thicker panes, but the thicker the glass, the greener the color becomes. The lower panes were originally designed by Mies to be sandblasted annealed glass, but safety glass is now required, and it’s not typically possible to sandblast tempered glass; and laminated or etched glass has a different appearance in sunlight. Neverthless, by working closely with glass manufacturers, the architects obtained sufficiently non-green clear glass and sandblasted tempered glass to maintain Mies’s original vision. Had the owner desired a less expensive and more rapid solution, the effect of using a different type of glazing would have severely altered the feeling inside the building and compromised its appearance from the outside.

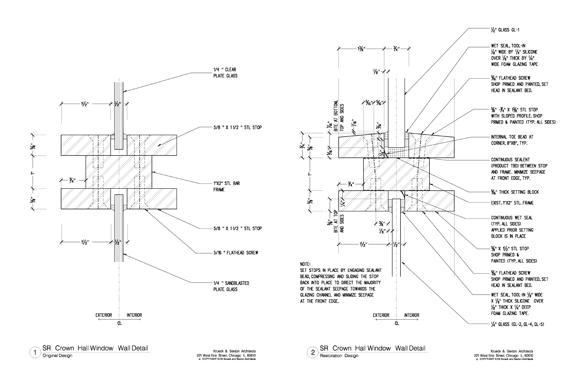

Minimalist detailing, characteristic of much Modern architecture, is taken to the extreme in Mies’s design of Crown Hall. Even a small change can have a big impact when the details are so spare, crisp, and controlled, and the sense of proportion so important. Architects designing a rehabilitation or adaptive reuse of a Modern building need to evaluate and understand the original intent of each detail, so they don’t inadvertently make changes that can completely alter a composition. One of the impacts of modifying the type of glass at Crown Hall was that the original stop design was no longer adequate to hold the thicker and heavier panes. So, while a thicker stop was accepted as inevitable, off-the-shelf components have an angled top, which was seen as incongruous in Mies’s right-angled composition. In the end, an expensive custom stop was designed that closely resembled Mies’s original and could support the new, thicker glass.

Many modern architects used innovative and experimental technologies in order to realize their design intent and to give the appearance of lightness and thinness. Innovative mechanical solutions were often incorporated into the building systems, including sophisticated methods of natural ventilation. Often the understanding of how these systems operate is lost over time, and they are not maintained. Mies incorporated operable vents into the top and bottom of the window system to allow cool air to flow in and hot air to flow out. Clogged by rust from the unmaintained steel structural system and by ivy growing on the outside, the vents had not worked for many years, leading many to believe that Mies had designed a completely sealed box requiring constant air conditioning. The restoration has allowed these vents to once again operate in their original manner. Understanding how and why the architect used certain technologies is critical to being able to rehabilitate such features.

Riverview High School

Completed in 1958, shortly after Crown Hall, Paul Rudolph’s Riverview High School in Sarasota, Florida, was also designed to open up to the landscape. In Rudolph’s composition, two-story classroom blocks and separate gymnasium, auditorium, and administrative buildings are gathered around an open courtyard. The buildings’ steel and glass skeletons allow for extensive views to the surrounding pine forests, and the pavilion-like quality of the campus provides ample opportunities to enjoy the outdoors. Carefully located floating concrete sunshades dominate the façade and exterior walkways, in order to protect glazed surfaces from direct sun, and were designed in conjunction with a complex natural ventilation system. Blaming concerns about security and the poor physical and environmental condition of the buildings, the School Board has recently decided that they will demolish and replace this outstanding work of architecture.

Rudolph’s’ desire for a campus of buildings that are open and connected to the outdoors is at odds with the school’s desire to control security and access. The natural ventilation system was never well understood and was replaced with a poorly functioning air conditioning system. When many of the concrete sunshades exhibited deterioration due to the thin and experimental quality of the concrete, the school decided to remove them, thereby overtaxing the building’s mechanical systems and obliterating Rudolph’s concept for climate and solar control. Finally, Rudolph’s’ very specific design for each of the program elements does not allow for easy adaptation without a great deal of creative thinking.

Unfortunately, the School Board has chosen to reject the Rudolph design and has not even attempted to solve these problems, many of which are of their own making. A more creative and sensitive approach would be to search for creative solutions to address each of the technical and program issues and figure out a way to rehabilitate the school and also restore the elements, which worked well in its original configuration, while designing new elements to solve the current programmatic problems.

The Challenge of the Integrated Whole

One of the most difficult aspects of rehabilitating a Modern building is that often the architect’s original concept is a highly detailed composition that serves a very specific purpose. Each element contributes to the aesthetic whole and functions together. But as building programs and technologies change, adapting parts of this total unity can greatly affect the character of the design. Either the new program needs to compromise in order to accept the over-arching significance of the original design concept, or some change that may obscure or modify the original design intent is inevitable. Being respectful of the innovative and experimental quality of the original design will typically lead to the best and most creative solution.

The restoration of Crown Hall and the decision to demolish the Riverview School are opposite approaches to addressing the technical difficulties of preserving significant Modern buildings. At Crown Hall, IIT took an almost museum-like approach to the restoration, understanding that each individual element contributed to the complete design, and that no item was too small to warrant careful study and understanding of Mies’s original thinking. At the Riverview School, the School Board decided that it would be easier to start from scratch with what will likely be a conventional and unmemorable replacement building than to try creatively to address the programmatic and technical challenges of rehabilitating a significant Modern building and updating it for today’s needs.

Author Andrew Wolfram, AIA, is an architect and senior associate at SMWM in San Francisco and was the Project Architect of the renovation of the landmark San Francisco Ferry Building, He is the president of the Northern California chapter of DOCOMOMO US, a national organization dedicated to raising awareness of significant works of modern architecture and design.

Originally published 3rd quarter 2006 in arcCA 06.3, “Preserving Modernism.”