Two major changes are set to alter the workplace as we know it and challenge organizations and designers in the process. First, our population is aging, and people will be staying in the workforce until much later in life. Second, new styles of work foster different modes of exchange between different generations.

Jeremy Myerson, Director of the Helen Hamlyn Research Centre (HHRC) at the Royal College of Art in London, describes how the contemporary workplace is increasingly the setting for new styles of work. He reports seeing a shifting emphasis from knowledge gathering toward knowledge management.

Furthermore, “knowledge capital” is an asset increasingly carried by the individual, not the institution. The exchanges between workers that contribute to the organization’s sense of intellectual capital will be characterized by greater sharing across generations. The challenge for organizations that seek to attract and retain workers in the competitive twenty-first century job market will be to re-think the kinds of work experiences that effectively foster knowledge sharing among an increasingly multi-generational workforce. In order to support the intellectual exchange among different generations, workplaces will need to be responsive to a much wider spectrum of values, needs, and abilities and to be inclusive for workers of all ages.

Skill shortfall

The dramatic aging of our population will impact our economy, as businesses will be forced to operate below capacity if they do not act strategically. Some industries—including healthcare, engineering, public services, and government—will be particularly affected, as they tend to have a large proportion of workers aged 50 and over.

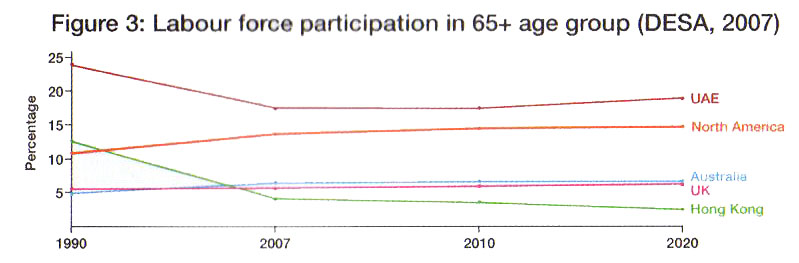

So what are some solutions to ease the pressure of a labor shortage? A 2006 article published in The Economist, titled “How To Manage an Aging Workforce,” suggests solutions such as moving production offshore, utilizing cheap labor from other countries, relaxing immigration laws, and using technology to increase productivity. An alternative is to utilize the abundance of older workers.

Despite approaching retirement, research suggests that the majority of older workers would rather remain in the workforce. Boomers are set to re-invent retirement and are likely to cycle between periods of work and leisure well beyond the age of 65. Older workers are now realizing that they won’t get the comfortable retirement lifestyle they planned for. Higher life expectancy is increasing the potential length of retirement, and if retirees want to spend their golden years in the way they planned, financial imperatives will push them back to work. Financial pressures aside, many employees want to stay in the workforce longer for the mental stimulation it offers, as well as to stay active and productive in society.

So, if employers need more skilled workers and older workers want to stay in the workforce, what’s the problem? A number of issues stand in the way of older workers being hired and/or retained.

Attitudes at work

Labor markets generally don’t work well for older workers; attitudes toward older employees can be negative, and recent age discrimination laws (particularly in Europe and the US), while making it harder for employers to dismiss older workers, can also make it harder for them to be hired in the first place. In addition, governments need to revise pension schemes and raise the age that people can receive entitlements to encourage them to retire later.

Employer attitudes will have to change if they want to retain workers—and knowledge capital. Perceptions that older workers are less productive, adaptable, creative, and more costly to manage are largely false. In fact, evidence suggests that older employees are better knowledge workers, give longer and more reliable service, offer a greater depth of skills and experience, and are less likely to take time off work due to illness, accidents, or injuries than their younger counterparts.

What older workers want

In 2005, an Australian Bureau of Statistics survey of workers aged 45–54 found that 90% thought that part-time and flexible work conditions would encourage them to stay in the workforce. One hundred per cent of people surveyed would like to work 2–3 days per week or work by assignment, such as three months full-time followed by a break. Their reasons for wanting flexibility in work hours include less stress, more time for personal activities (including caring for grandchildren and travel), and the opportunity to work on tasks or projects that best utilize their skills and knowledge.

In 2006, recruitment company Hudson published a research paper, “The Evolving Workplace: The Seven Key Drivers Of Middle-Aged Workers,” which identifies the workplace motivations and aspirations affecting older workers’ participation in Australia and New Zealand. The survey of 1135 workers aged 40–70 years found that if offered more flexible and attractive work conditions only around 1% would choose to retire. Forty-seven per cent would be prepared to work full-time, 21% would work part-time and a further 20% would choose to stay employed on a contract or consulting basis. The key drivers affecting this choice include commuting time to work per day, pay conditions, a friendly work environment, feeling challenged at work, recognition, flexible working hours, and the ability to work from home.

Designing the multi-generational workplace

With the combined forces of an aging population, changes in retirement trends, and a push to retain knowledge and expertise, there is no doubt that older workers will stay in the workplace longer, increasing the age difference of people working in the same environment to as much as 60 years. The problem with contemporary workplaces is they too often cater to the tastes and needs of Generation X and Y and are ill equipped to meet the needs of a multigenerational workforce. As Jeremy Myerson describes in Woods Bagot’s publication Public #4: 21st Century Guide to Life (2008), “All that glass and steel, all those hard surfaces and glaring overhead lighting grids and precarious office stools … The modern workplace adds up to an acoustic, visual, and physical nightmare for an aging workforce.”

So, how will designers respond to the needs of an aging workforce? Researchers at the Helen Hamlyn Research Centre (HHRC) have been investigating ways to design inclusive workplaces, appealing to the widest range of ages and abilities. Under the guidance of Myerson, a research program of industry-funded studies into design for older workers, entitled “OfficeAge,” explores the ergonomic, psychological, and physiological needs of aging knowledge workers, as well as their motivations and ambitions for life beyond work, and considers the needs and hopes of older workers within the context of current trends in work technologies and workplace structures.

The World Health Organization’s “Study of Aging and Working Capacity” (1993) found that changes in motor and visual systems associated with aging will affect working needs. For example, older workers appear to be more sensitive to heat, cold, noise, and light changes. The studies undertaken by the HHRC have begun to identify ways in which the workplace can respond to these changes. Through these and other findings, mature-aged workers are calling for lighting and acoustics that are more comfortable, furniture and equipment that is adjustable and has better ergonomic features, and technology that is “softer” or more intuitive. Older workers are concerned with health and want access to organic and tactile environments, green spaces and natural light, as well as environments that actively monitor heath and encourage healthier work habits. They want greater control over where and how they work, with access to comfortable and varied settings for both private and collaborative work.

If designers can respond to these needs, workplaces will not only be easier and more enjoyable to use for older workers, but for people of all ages. Everyone will benefit from increased levels of comfort, flexibility, and usability.

Concluding thoughts

There is no doubt that the workplace is graying. Just as environmental sustainability is at the forefront of workplace design today, socially responsible workplaces that consider the needs and abilities of a multi-generational workforce will lead the way in the workplace designs of tomorrow.

While research into how the physicality of workplaces will need to respond to an aging workforce is still in its infancy, designers need to make this issue part of their dialogue and start to consider how the future workplace might look, as well as what tools they might need to help them design for a multi-generational workplace.

If workplaces can be designed that cater to a wide range of needs, abilities, and values, work environments will not only be more comfortable and enjoyable for everyone to use, but will encourage our most experienced and knowledgeable workers to stay and “play” a little longer.

Andrew Lian leads workplace sector projects at Woods Bagot Perth Studio and has a strong interest in research of future workplace trends. He has been recipient to both academic and professional awards. Andrew is a registered architect with over 18 years project experience across Australia and South-East Asia. Carolyn Karnovsky is the Marketing Coordinator for Woods Bagot Perth Studio. In 2005, she received her BA in Product and Furniture Design and has worked both as a research assistant and sessional lecturer for Curtin University’s Faculty of Interior Architecture. Lauren Zmood is a member of the Workplace Consulting team at Woods Bagot. She recently completed her Masters in Architecture with first class honors. During her studies and work, Lauren’s interest in research and theory led her design projects to explore current and future social, contextual and sustainable elements.

This article is adapted with permission from a longer white paper of the same title prepared by the authors at Woods Bagot, which is developing a suite of tools to evaluate workplace design and flexibility for older workers and to assess how well the physical environment supports and inspires a multi-generational cross section of workers.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2009, in arcCA 09.2, “Design for Aging.”