Be it a decorated altar, grove of trees, or cozy corner of the couch, most of us need a sacred space to turn to for tranquility or connection to a higher power. For the residents of Black Rock City— the bustling yet ephemeral home to the annual weeklong Burning Man festival in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert—that sacred space comes in the form of a wooden temple.

Rising from the flat, powdery earth, or playa, the temple serves as a spiritual refuge from the wild happenings elsewhere, a gathering space to meditate, mourn, or simply seek shelter from the sweltering sun. While most temples are meant to stand in perpetuity, the Temple of Flux, as it was called in 2010, was incinerated in a carefully composed performance at the end of the event—a fiery reminder that everything changes and eventually disappears.

An Organic Counterpoint

Whereas previous Burning Man temples were typically elaborate, multistoried structures that called to the imagination shrines of foreign lands, the Temple of Flux took a radically different approach. Inspired by natural landforms, it appeared as a series of five graceful peaks that were broad and heavy at the base and ascended to a porcupine-like edge angling toward the sky. The walls were laid out in linear overlapping layers of plywood, from large rectangles to long, thin strips, and framed a central chamber that signaled to visitors they had wandered inside. Each dome contained at least one cave-like hollow. Light and shadow, both on the walls and in the chamber, gradually shifted throughout the day to reflect the pathway of the sun.

Led by Rebecca Anders, Jessica Hobbs, and Peter Kimelman, the design explored the continuously shifting relationship between humankind and the physical environment.

“We were prompted to ask where we came from,” said Anders, a Bay Area sculptor and metal fabricator, during an onsite tour at Burning Man. “Humans originally sought shelter in the land, in caves and canyons. Then we tried to alter these formations, then build our own structures.”

As an organic, sensuous art piece, the temple stood in unexpected contrast to this year’s festival theme of metropolis, in which one might anticipate seeing a more rectilinear form. In fact, the team consciously opted to create the first temple that was not a traditional building.

“We were interested in these shapes for their special abilities to enclose, to limit exposure to the outside,” said Kimelman, a Bay Area architect. “Visitors were forced inward, with only the earth and sky to focus on.”

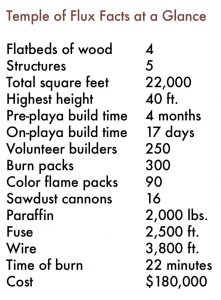

While the Burning Man organization has historically selected its temple designers by proposal, it invited these artists directly. Once they settled on the idea of the urban canyon, they generated sketches and models while simultaneously beginning the intense process of cutting, painting, and piecing together plywood at American Steel in West Oakland, an enormous workspace run by established Burning Man artists. Several teams were developed, including structural engineering, construction, burn logistics, and fundraising. The smallest structure, which served as the test case, was rebuilt several times to perfect the design and prepare the team for the overwhelming task ahead—building all five structures in the desert’s extreme, unpredictable environment of high winds, blinding dust, and blistering heat. Over the next four months, more than 250 volunteers lent a hand, from seasoned builders to people who had never picked up a power tool.

“Burning Man, as a culture, is built on collaboration,” said Kimelman. “Teaching volunteers how to cut wood, what shapes to use, or how to use a nail gun is part of the goal of making large-scale art.”

A Place to Reflect

Some of the world’s most poignant memorials, such as the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem or the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., invite visitors to interact with them in some way, to make an offering. That opportunity, in fact, drives many people to attend Burning Man. With busy lives that often lack a strong spiritual outlet, visiting the temple may be their only chance to reflect, to grieve, or to let go—of a person, belief, or bad habit. By the end of the week, the temple, which starts off as a nude wood form, is embellished with photos, letters, affirmations, objects, and other contributions that run the gamut from humorous to hurt, celebratory to sad.

Caroline Grier of Oakland, a long-time Burning Man participant, visits the temple several times each year, but nothing prepared her for this year’s experience. She was having a bad day, a bum knee, broken bike, and other aggravations triggering deep frustration she was experiencing at home. She climbed to the top of the man, the iconic 50-foot-plus effigy set atop an elaborate platform, and suddenly felt a powerful urge to jump.

“I felt the momentum of it, the possibility of it,” she said. “I was done with the pain.” But she found her way to the temple instead and began reading notes to the departed, including people who had committed suicide. In fragment after fragment, Grier witnessed pure grief and love.

“It occurred to me that some of my camp- mates would feel that way about me, and something shifted,” she said. “The temple saved my life.”

Since then, Grier has made a promise to let people know they are loved and appreciated. It’s these kinds of altering experiences for which the temple is revered.

Majesty of Flames

The festival’s culminating events are the burning of the man and the burning of the temple. After so much work involving so many people, why would these intricate pieces be demolished? Logic aside—lugging thousands of pounds of wood back to the Bay Area is impractical—the act speaks to two cornerstones of the Burning Man community, that the process surpasses the product, and that nothing lasts forever. The entire city is dismantled and the playa returned to its pristine state within days of the festival’s end.

Quayle Hodek of Boulder, Colorado, has attended nine times. “The temple holds an amazing lesson of impermanence,” he said.

“So much goes into something that’s only around for a short time. Then it’s set free in a majesty of flames and heat.”

The burning of the man is a raucous affair, as if Halloween, New Year’s Eve, and Carnival are rolled into one. But the burning of the temple is quiet, solemn, imbued with a tangible feeling of reverence as onlookers set their intentions on letting go. The moment’s poignancy is not only in the individual things that are being released, whether that’s a broken heart, substance use, or the loss of a parent, but also in the silent, collective witnessing of transformation.

Hodek had placed a note and photo in the temple on behalf of a friend whose young sister had died mysteriously just weeks before Burning Man. When the fire started, he was captivated by its immense heat and speed as whirling masses of air and flame engulfed the structures. “It was a powerful experience,” he said, “a way to hold space for a friend who needed it, to memorialize a life in the midst of others who were enjoying theirs.”

And that, for many, is what Burning Man is all about. Honor your life now, because it could change in a flash.

Author Amy Cranch has worked as a writer/editor in the nonprofit world for 18 years—first in social services, then at museums, and now with UC Berkeley. She is also a lifelong yoga practitioner, dancer, and theater artist, performing today under Anna Halprin and Nina Wise.

Originally published 4th quarter 2010, in arcCA 10.4, “Faith & Loss.”