From Glitter Stucco and Dumpster Diving: Reflections on Building Production in the Vernacular City (NY: Verso, 2000).

The requirements of professional empire building apart, the demand that all buildings should become works of architecture (or the reverse) is strictly offensive to common sense. —Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter, Collage City

Nearly all items in the human landscapes reflect culture in some way. There are almost no exceptions. Furthermore, most items in the human landscape are no more and no less important than other items—in terms of their role as clues to culture. —Pierce Lewis, “Axioms for Reading the Landscape”

How do those of us inculcated in architectural culture coexist with the world around us, which largely ignores the values and rules of high-art architecture? What is the relationship most of us have to the actual built environment around us? How do the buildings that we see from the freeway, the developer housing, the blank-faced speculative office buildings and the shopping malls get designed? How do they [a]ffect the quality of our lives? Those are primary questions at the turn of the century.

Building production is a term for the sum total of the built response to human needs. A building-production typology is the roll call of categories of buildings, land uses and activity types that answer the needs of a community. It is the complete listing of additions to the man-made physical world, understood not only in terms of appearance, but in terms of purpose: why individual buildings came into being and the role each plays as part of a consumerist society.

Not all buildings address the full range of architectural concerns. Some buildings may be about revealing the means of their construction, and others about the masterly handling of light and space. Still others may be concerned with beautiful ornamentation or with ingenious methods of prefabrication. Architecture, in its broadest sense, allows for both the highart building as well as for more populist work with a wider audience. In the system of building production one is not judged as being better than the other; both are subject to judgment according to their own ground rules. The ability to communicate to the public, to symbolize, embody and create emotions and experiences, has largely fallen to consumerist architecture—most populist architecture could be judged as consumerist architecture, architecture that must perform, must contribute to the experience of patronizing the building, in order to function economically.

The notion of type is primary to the study of the built environment. Building type can be defined as a set of programmatic and morphological attributes that are shared by a set of buildings. In order to constitute a type, a group of buildings must share enough programmatic determinants of form that each one effectively calls up and represents all the others. The notion of type, in a sense, depends on a program with such specific needs that it puts its stamp on each building of its kind. Building types such as grain elevators and water towers are products of their storage functions. Theaters (even movie theaters, before the advent of the multiplex cinema) are marked by the tower of their proscenium and by their projecting marquees.

Architectural culture tends to overvalue the importance of the individual architect in determining the nature and design of buildings and to underplay all other factors. The notion of type has the virtue of emphasizing the forces of creation that buildings have in common, of finding links across time and space. In addition, the notion of type allows buildings to be seen as a hybrid of style, program, economics and construction practices. It takes into consideration the economic incentives for the building’s construction, the method of its construction and use for which it is intended. Only then is the role of the architect considered.

As Pierce F. Lewis wrote: “The fact that all items are equally important emphatically does not mean that they are equally easy to study and understand … Sometimes the commonest things are the hardest to study…”

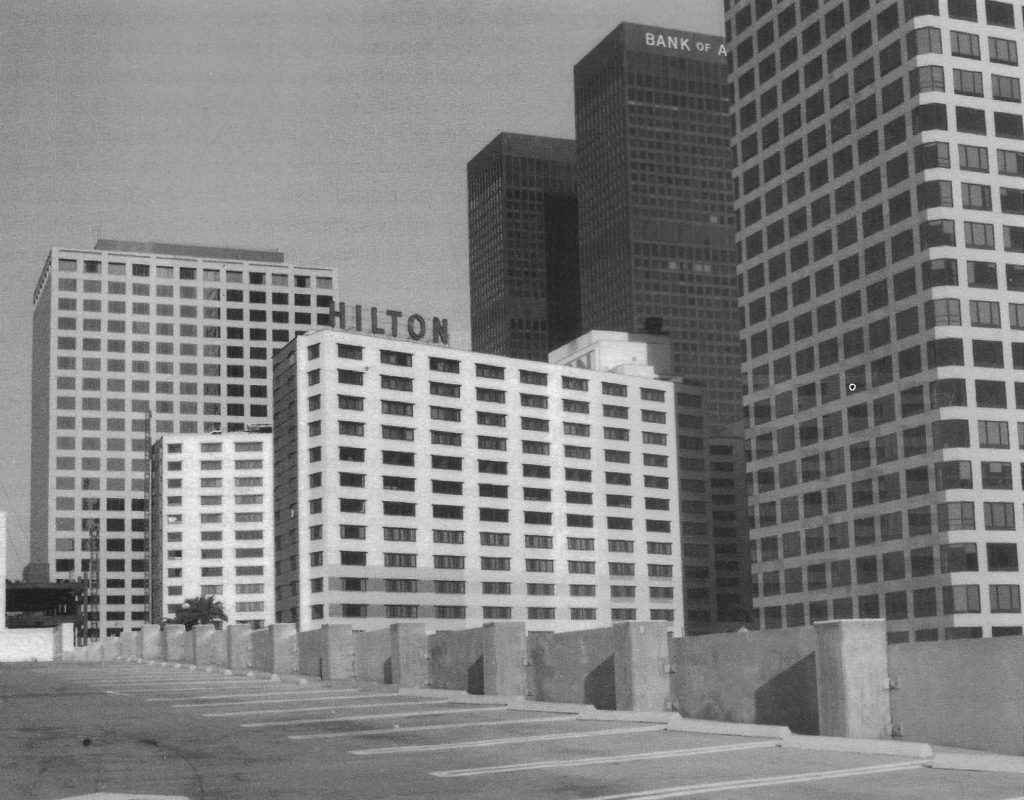

The most common elements of what Lewis calls the cultural landscape and what I call building production—motels, tilt-slab warehouses, shopping malls, parking structures and parking lots, ice vending machines and concrete-block warehouses—are the most difficult to see because they present the problem of never having been encountered for the first time, and certainly never in a reified, honorific or even especially focused way. They are so ubiquitous that they present a conflict between the role every designer has as an inhabitant of the world, using and accepting that world as he or she finds it, and the role of the designer as changer of the world, imposing upon it some degree of new order.

A typology of building production elaborates the roster of types, listing what representatively houses the activities found in American towns in the present. It describes and analyzes these building types, types that often remain outside architectural culture, from car washes to tract housing; from hybrid hotel/casino/entertainment attraction complexes to self-storage facilities, mobile home parks and speculative office parks. It also includes structures that exist without official permission, such as shelters built by the homeless and buildings that have been modified without benefit of permit, such as garages converted into extra dwelling units. Some land uses may not be represented by a building type, such as the temporary special event nightclub or the garment workshop.

It is important to categorize the sum total of recent building-production types. Because most architectural history and criticism is devoted to high-art architectural production, the backdrop of overall building production within which this architectural production is set, the larger physical environment, does not receive attention sufficient to its predominance. When this broader built environment does receive attention, it is often in a trivializing or patronizing fashion that indicates a lack of interest in attempting to understand the factors that bring the non-high-art sectors of building production into being.

It is simply impossible to avoid having a relationship to the world around you. In the United States, at the turn of the millennium that world includes shopping malls, fast food, auto-dominated environments and segments of architectural production that involve popularly understood iconography.

As Ian Chambers explained in Popular Culture: The Metropolitan Experience, “The previous authority of culture, once respectfully designated with a capital C, no longer has an exclusive hold on meaning. ‘High culture’ becomes just one more subculture, one more option, in our midst.” He continues, “Today, the metaphysical separation between idea and material, between original and derivative, production and reproduction, taste and commerce, culture and industry has collapsed. The struggle over ‘Culture’ may still be staged, at least in the universities, learned journals, art galleries, official cultural agencies, ‘serious’ literature, cinema, journalism and television, between these assumed oppositions. But popular culture has bypassed the question. It is popular culture—its tastes, practices and aesthetics—that today dominates the urban scene, offering sense where traditional culture can usually only see nonsense.”

Architects and designers need to know about the context in which they build, and about the companion structures outside of conventional high-art architectural practice, including those not generated by the rules of, or for the typical clients of, high-art architecture. Planners and urban designers also need to understand the actual fabric that makes up the built environment in the United States. Historic preservationists need to have a sense of the overall character of building production if they are to assign significance to individual buildings as exemplary of a formerly common building type that is now becoming rare through the rapid pace of commercial obsolescence.

In contemporary American society, cultural meaning is largely created through consumerism, through the means of consumption and production. High-art architecture tends to be honorific and possesses a hierarchical value system that honors places and situations associated with money, power, prestige, fame and conventional architectural culture. This latter culture ranks architects by aesthetic creativity, commodifying those at the top of the profession. The issues on the table are the architect’s ability to master space, structure, light, programmatic organization and the making of objects. This architecture requires a great deal of effort, a scale of effort that most people either simply can’t afford or don’t want to pay for even if they could.

Architects and designers are products of the cultures of architecture and design. Their values, beliefs and preferences tend to direct their awareness quite naturally to the sector of building production that most validates these cultures. As a result, most architects are trained to focus on certain building types, such as the museum, the private “custom” home and the government office, as being more important than other building types, such as concrete-block automotive repair shops or corner minimalls. Consequently the built environment is selectively understood in terms of the ability of architectural culture to meet its own aesthetic standards, rather than in terms of the different roles that individual building types play, or what makes up the actual fabric of American communities.

This book focuses on building types that often remain outside architectural culture because of cultural viewpoint and or financial limitations. Building types such as the freestanding doughnut shop or the roadside convenience store are part of people’s everyday lives. Land uses such as the homeless occupation of public space and street vending are expressive parts of the city. Structures such as the residential subdivision and speculative office buildings form the fabric of contemporary America. None of these have received sufficient critical attention from the point of view of typological study, nor have the economic factors that bring them into existence been sufficiently studied. Users of the as-built environment, such as warehouse-supermarket consumers, laundromat users, the employees at tiltslab warehouses and the residents and caretakers of single-story post-World War II nursing homes should have the building types that they use on a daily basis considered a legitimate part of the built landscape, not because of aesthetic merit, but because these building types are integral parts of daily life and American culture.

For example, why not consider residential building types—such as traditional, center-hall tenements; mobile homes; garden apartments; courtyard apartments; high-rise apartments; row houses; town houses; detached single-family houses, duplexes and triplexes—and classify them according to factors such as provision of parking; site-plan building form and footprint; unit floor plan; relationship to the outdoors; morphology; economic strata and level of amenity; relationship to the automobile; lack of parking; surface parking; exposed, tuck-under, ground-level building parking; semi-subterranean, subterranean or multilevel subterranean. In many cases, style is the final element of the typological classification—as in the popular ranch house or the Tiki-garden apartment house.

An example of this kind of analysis is Richard Longstreth’s study of department stores and retail centers in City Center to Regional Mall. Similarly, the department store can be considered as a set of types according to its location in a conventional downtown, a strip center, an unenclosed shopping center, an enclosed shopping center or an urban entertainment district; its floor plan, number of stories and amount and placement of window and display areas; and its relationship to the automobile. For a movie theater, the same issues of relationship to site, such as location in a mall or on a conventional street, and relationship to the automobile would also apply, along with other factors such as the building’s original identity as a single-screen house or multiplex, the scale of the mythic overlay attempted, the presence or lack of a symbolic tower, the expression of the backstage and the incorporation of other uses (such as stores) into the theater building or the incorporation of the theater into another building (such as an office).

Ultimately, studying this typology illuminates the changing character of the American landscape and creates a better understanding of its constituent parts. The goal of a typology is to clarify the relationship that exists between individual citizens and the culture of American consumerism.

There is still much to be discovered about the role building types and land uses play in the contemporary American community. For example, the recently published “Preserving the Recent Past” conference proceedings edited by Deborah Slaton and Rebecca Shiffer points toward an unfilled need for clearly established criteria for judging, observing and classifying the architecture of the recent past. Other applications include planning, especially in rethinking categories of land-use zoning; architectural history, particularly vernacular history; and the teaching of design in architectural schools, as an aid in understanding actual urban context.

I have already posited various categories of building production, with their relationship to consumerism as the ordering principle. The next step is to develop a system of classification for building production that encompasses the full range of contemporary building types by their function and economic purpose as well.

The creation of a fully fleshed–out typology of building production must be based on field observation and the use of primary sources. It is better to sort through the as-found built environment to find sites, and then research them, than to proceed from sites of previously determined historical or architectural interest and then to research them on a site-by-site basis.

In the long run, a typology of building production is intended to illuminate the contemporary urban landscape in a way that is redemptive, one that allows for creative reinterpretation on the part of individual designers, architects and citizens, so that we can react to consumer culture and appropriate it rather than just being passive consumers of it—or being overpowered by it.

At the time of his death in 2010, author John Leighton Chase was Urban Designer for the City of West Hollywood and a member of the editorial board of arcCA (Architecture California), the print predecessor of arcCA DIGEST. His books include Glitter Stucco and Dumpster Diving: Reflections on Building Production in the Vernacular City, from which this essay is reproduced by permission of his estate; Everyday Urbanism, co-edited with Margaret Crawford and John Kaliski; The Sidewalk Guide to Santa Cruz Architecture; L.A. 2000+: New Architecture in Los Angeles; and Exterior Decoration: Hollywood’s Inside-Out Houses.

From arcCA DIGEST Season 09, “Typology.”