Because the contemporary West still owes a profound intellectual debt to the ancient Greeks, it is all too easy to misinterpret our understanding of things and terms as identical to theirs. The Greek idea of freedom, for example, was very different from the consumer-culture definition of it as, more or less, being in a position to gratify all possible appetites. Instead, almost exactly to the contrary, it was understood to be the condition of having risen above need, to be as much as possible beyond the grasp of anyone’s or anything’s force, including your own body’s desires and demands. Freedom, beyond Necessity, was necessary in order to be able to make dispassionate judgments and thereby to appear, act, and argue justly within the polis.

Such an ideal produces attitudes that carry beyond ethics and politics. Hence the ancient Greek parable of the games or the theater, attributed to Pythagoras, which defined three classes of people who attend the events. There are those who come to sell their wares (presumably things like Hermes statuettes or the Greek equivalent of hot dogs); these people are doubly unfree, because they are subject both to the constraint of the materials within which they work and to the judgment of the potential customer. Similarly twice unfree are those in the second group, the actors or athletes, bound as they are to a script or engaged with an opponent, and beholden also to the spectators for approval. The third group, highest because most free, is the audience, those who come to the spectacle simply to look on.

Legitimate knowledge was thus defined, at least for the post-Archaic Greeks, as fundamentally spectator knowledge; things known to the eye, things that can be made to appear in public, as it were, were given privilege over the knowledge that could be produced by other sorts of engagement with the world.

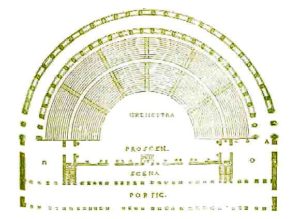

Here is where the Greeks found difficulty dealing with buildings. The first big problem is this: when you go inside a building you quite literally cannot be theoretical, because you cannot “spectate” it, cannot view it from outside. Greek theaters were open-air, not just out of convenience but out of theoretical necessity. When inside any other sort of building, no matter how you turn, the enclosure you wish to see insists on keeping half itself back behind your skull. Being inside a building is like being an athlete-competitor enveloped in the grasp of a very large, unbeatable wrestler, subject to his will, subject to Necessity. You are forced out of the condition of being an observing eye and put back into existence as a human body, a body of a certain limited size, engaging the flux of the world. It is no wonder that the Greeks also habitually conducted their politics in the open air, and that processions were brought up short of entry to temples. The fact that buildings enclose was profoundly disturbing.

The second difficulty with buildings, and particularly with a house and its land, is their stubborn will to endure in a place. This is really a multifold problem. To begin, the obligation that a citizen possess a house, be head of its household, is a logical embarrassment, for it is paradoxically the necessity required to rise above Necessity. Furthermore, the material obduracy of a building, its resistance to reacting to human presence or action, is a kind of insult, since assent to conversation as equals is what every citizen grants another. To the extent that architecture is solid and endures, the building’s indifference treats the viewer as a mere body, invisible as a slave, which can own no house but only be contained by one. Third and perhaps most basically, architecture also exists in a place, which endures absolutely.

The Greeks paid a great deal of attention to place-ness. Aristotle, for one, devoted four chapters of his Physics to discussion of it and concluded that place is in its essence non-generalizable. As the vessel of particularity, it is the ultimate anti-Idea. To the extent that language is about, and made up of, ideas, it cannot meaningfully discuss place.

Major consequences ensued from what modern (i.e. Post-Renaissance) culture has done with its Greek patrimony—for, of course, the eye-knowledge of the theater was given privilege, and the house became invisible. Bruno Latour, a historian and sociologist of science, has proposed that the uniqueness of modern, Western, technological culture lies in the distinct ways that writing and imaging have been used in knowledge-definition and the production of power. He contends that its distinct character arises from increasingly sophisticated employment of what he calls “immutable mobiles,” by which he means all the ways of writing down and making pictures of observations made in one place, so that their documentation can be transported intact for use in another place. There, they are considered, compared, used in arguments, which then suggest a new round of observations, which in turn result in new batches of immutable mobiles and arguments from them.2

The effects are very different from that of a bit of knowledge kept in one place, to demonstrate which Latour uses two maps as an example. The French explorer La Pérouse asks a Pacific islander to draw a map of his island. The man complies, drawing in the sand with all the scale and details needed, while La Pérouse copies on paper. The first map is lost to the tide; the second, an immutable mobile, is taken back to Versailles and used in an argument that leads to trade and eventually to subjugation of the island.

This sort of knowledge-production began to be habitual in the West more or less at the onset of the Renaissance. It encouraged and in turn was aided by a series of inventions beginning with the printing press and perspective drawing. A cascading effect occurred and accelerated, cycle upon cycle.

If the only significant aspect of reality is that which can be gotten down on paper and used, then the characteristics of architecture that participate in what I have been shorthandedly calling house-knowledge are clearly in big trouble; obduracy and enclosure are simply untranscribable. The value, for providing knowledge and power, of the aspects of architecture that the theater tries to avoid and the house exaggerates is thereby now made doubly suspect. Within such a cultural situation, the evidence of the individual senses will tend to be valued in direct proportion to its being transformable into a mobile document. To the aggregation of the senses— that is, the experience of being a body in a particular, unique, immovable place—the culture’s participants will be increasingly blind. Enclosure must therefore be removed and obduracy regarded as an impediment. Buildings, in self-defense, acquire document-envy.

The history of architecture since the Renaissance is at bottom the sequence of accommodations to the increasingly pervasive domination of documents in the culture. Latour lists five desirable properties of immutable-mobile inscriptions which, by extension, become similarly desirable aspects of objects within the culture: things must be made to be not only mobile and immutable, but presentable (that is, visible together), readable, and combinable. (Perhaps a time-qualifying corollary to immutable should be added: disposable, since once an object or document has been read and has helped initiate a new cycle of the system, it becomes superfluous.)

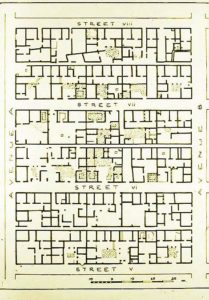

The architectural cognates are evident. Mobility being difficult, flowing universal space must be invented as a substitute. Immutability can be approximated by universality, the idea that one architectural vocabulary could suit any culture or situation. Presentability induces the mania for clarity and openness both inside and around buildings; goodbye to the bearing wall and the hidden corners of the traditional city. Readability was to be attained by rigorous visibility and clarity of structural system. Finally, combinability’s architectural translation would have to be the tendency to dissolve the recognizable distinctions among building types. (Bentham’s Panopticon is simply a device for turning houses into a theater.) The Modern Movement, for all its many variant versions, now looks not like a new beginning but instead the logical culmination of immutable-mobile envy.

The last quarter century’s buildings and theories were not only attempts to deal with the perceived shortcomings of the Modern, but also recognitions of the culture’s pervasive, document-based, immutable mobile system for defining legitimate knowledge. Postmodernism wrote postcards reminding us of obduracy and interiority, mostly without suggesting we could really go back and live with them. Deconstruction scribbled the charge that architecture’s attempt at simulation of documents had failed; not only that, but the attempt had been halfhearted from the outset. The thing to do was to abandon all vestigial interest in material obduracy and spatial interiority, and operate on the principle that your design was first and foremost a document, because the document was better understood and more highly valued, in contemporary culture, than the building. Thus the characteristic operations of Deconstructivist design were, strikingly, those pertinent to manipulating paper: collage and erasure, cut and paste, photocopy and crumple, fold, spindle, and mutilate.

The ideal Postmodern building type is the museum, and the last quarter of the 20th century not accidentally witnessed the greatest museum-building binge in history. The very concept of the museum depends on the idea of objects being treated like immutable mobile documents. Problems occur when suspicions arise that an object really can’t be understood without knowing about its original context. The paradoxical impulse when such suspicions take hold is of course to establish a museum of contexts trucked in to supplement the museum of immutable mobiles, and the source of much of the museum-building impulse in the period in question is exactly there. Not only did art museums proliferate—every place was determined to assert its place, and first-rate art museum buildings showed up in secondary cities like Fort Worth and Mönchengladbach—but there was also a revealing multiplication of institutions devoted to examining “material culture” on both the folk and the technological ends of the spectrum. Oddest of all, odder even than the idea of the transportable tragedy implicit in, say the Holocaust Museum in Washington, is the architecture museum; the very conception of such a thing is impossible when obduracy and interiority are considered fundamental attributes of architecture.

Subsequent to Postmodernism, there emerged no single building type particularly attractive to Post-structuralist impulses—”type” itself is suspect, of course—but one notes a constellation of projects that center on announcing the importance of evanescent human movement: parks, highway installations, performing (rather than visual) art centers. Post-structuralism’s self-chosen fate, its vigilant editorial grimness the necessary inverse of Postmodern attempts at wit, is to quiz the language-sphinx which it already knows will never answer, and therefore always to understand the world around as desert.

Well. Where do we go from here? What do we take from the last quarter-century into the millennium? I have two suggestions for consideration and action, one general, one specifically addressed to those of us who play a role as architectural educators.

As educators, teaching the people who, we hope, will be rebuilding—and unbuilding, where appropriate—the earth, I think we can be of service by calling up obduracy and interiority for consideration and questioning. The design studio is, after all, a participant par excellence in the economy of immutable mobiles: documents dominate, and by definition obduracy and interiority cannot be present. Perhaps it is possible to at least bring them in by implication by returning periodically to the very un-simple matter of the size (not scale) of the things being designed. To do so is not necessarily anthropocentric; quite the contrary, it is to gain a sense of the reciprocal formation of our selves and the world.

The second suggestion is to consider again the relation of architectural obduracy and interiority to language. If architecture does have aspects unconditioned by language, what are the consequences? Here is another speculation. Language use does not appear in children until after their appreciation of the difference between themselves and the world, between themselves and their two parents. Could our difficulty with obduracy and interiority be because the experience of them is a reenactment of the initial, pre-speech, human desire to overcome the indifferent obduracy of the father and gain recognition as connected, and at the same time overcome the overwhelming interiority of the mother and gain recognition as separated? The wish implicit in all would-be-enduring monuments is to lose individual human fragility in collective, obdurate, material commemoration, to go back into the house of our ancestors and descendants. The wish implicit in the universal space, neither sacred nor profane, through which immutable mobiles travel, is to emerge from the interior of the body to stand free, an eye in the theater of the world. We are fated, or evolved (which term does not matter) to hold both wishes. Deeper and older than language, they may be the origins of architecture.

1 Hannah Arendt, The Life of the Mind (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1971), p.93.

2 Bruno Latour, “Drawing Things Together,” in Michael Lynch and Steve Woolgar, eds., Representation in Scientific Practice (Cambridge, Mass.: Mit Press, 1990). See also Latour’s “Clothing the Naked Truth,” in Hilary Lawson and Lisa Appignanesi, eds., Dismantling Truth: Reality in the Postmodern World (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 1989).

Author Patrick L. Pinnell, AIA, is an architect and town planner in Haddam, Connecticut. This article was originally written in 1992. After a decade, its insightful assessment of architectural thinking in the last quarter of the 20th c. is undiminished. We reprint it here by permission of the author.

Originally published 1st quarter 2003, in arcCA 03.1, “Common Knowledge.”