This is supposed to be the Future. You know, the Future the Jetsons showed us. The one of an easy life made easier by gadgets, computers, robots and instant communication. Yes, George had to put up with a grumpy boss and spaceship traffic jams, and technology gone awry was a recurring plot, but Future life was essentially a ‘50s suburban existence made even more effortless by invention. We were reassured by this Future: it was a lot like the past.

So what happened? How did we end up instead as if in James Gleick’s Faster, where just the act of reading this book races the pulse with the familiar anxiety of being late for a crucial appointment, of impending deadlines, of opening e-mail to find 21 new messages before lunch (and none of them Spam)?

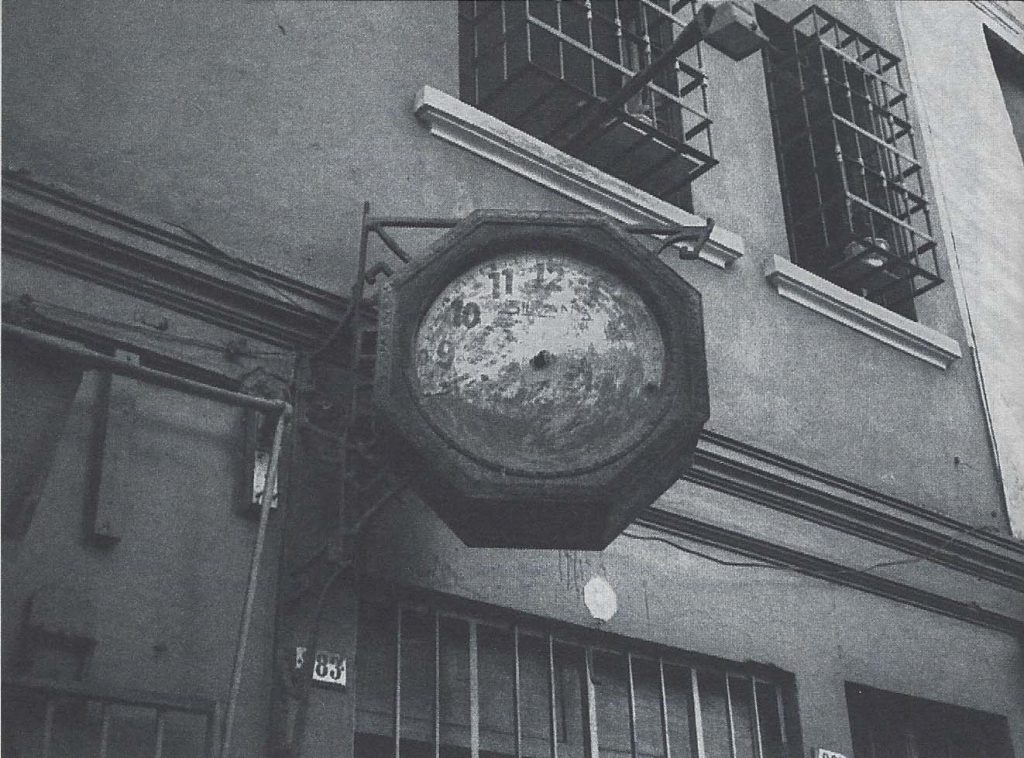

Much has been made of the observation that where we used to measure our lives in days, then hours, we now measure them in seconds-even nanoseconds. Megahertz and bytes are becoming the new standard of time. Analog clocks are no longer precise enough, the digital clock on my computer screen reminds me.

There is no denying the general craving for speed: the speed of transportation, communication and production but also the speed of wish fulfillment. We want the physical world to keep up with the world of our fantasies. We can envision a work of architecture instantaneously realized, but concrete still takes 28 days to cure. Our bodies demand food and sleep, our old-fashioned hearts require recreation and human contact, and despite ever-faster chips and cable connections, computer processors still take time.

These days we put technology to work to compensate for the drag society places on us. We make phone calls from the car. We grab fast-food breakfasts, have lunch at our desks and zap something in the microwave while checking our messages late in the day. We use melatonin to slam us to sleep and coffee to jolt us up. We compensate for social contact through hyper-connectedness-making ourselves available electronically to everyone, all of the time.

That kind of pace is seductive to a culture in which it is universally accepted that fastness equals efficiency, and that inefficiency equals lack of intelligence, laziness or both. But what does this obsession with speed do to the architect, the practice of architecture and the buildings produced? With the current economy and boom in the demand for architectural services exists the vague fear that the prosperity could disappear at any moment. So, making hay while the sun shines, architects take on almost every project that comes in the door while nervously watching the horizon for clouds. The result is a mountain of projects, not enough staff, growing concern over liability and, at the center of it all, never enough time.

I Can Be Reached At ……

It’s hard to know exactly how the invention of the telephone affected architectural practice; that’s ancient history. But most architects working today vividly remember the introduction of fax machines. Suddenly there was a way to convey drawings as easily as telephones conveyed words. It seemed like magic. And it saved a lot of the time that had been spent physically transporting drawings from office to job site, from consultant to consultant. But the instant nature of the fax meant that clients and consultants wanted instant responses. We were expected to keep up.

Coincidentally, answering machines became an office fixture. Now people could call in off-hours to leave the first messages retrieved the following day. In rapid succession came pagers, call waiting, e-mail and cell phones, each granting the “convenience” of always being reachable. No longer could we be out of touch, unavailable, simply busy with something or someone else.

Better Practice Through Technology

Architectural practice has always been eager to fold in technological advances that help with production and with the coordination of information. Diazo and Xerox machines were rapidly adopted. Though they are now ubiquitous for production (still not for design in many offices), computers were slower to gain acceptance.

Certain kinds of software represent an amazing advance in the practice of architecture. In the construction document phase, they allow for and keep track of changes and immediately re-dimension everything on adjustment. This is particularly useful for small offices and sole practitioners who perform every role. Almost impossible architectural forms, most notably Bilbao, have been built using computer-interface technology that directs material fabrication.

Hurry Up

Clients, with interest amassing daily, apply pressure for everything to go quickly. When the architect is able to comply, there is the assumption that lower fees should result. Nothing is further from the truth. Fast-track projects do not equal more efficiency or less cost for the architect; rather, the reverse occurs. Multiple sets of drawings are required at various points in the stream of production in order to meet the permit submittal schedules. They are also required during construction. Even with the help of clever computers, coordination of these drawings, which is one of the keys to high-quality delivery of a project, can easily be compromised.

As if this were not enough, the requisite meetings come fast and furiously. The recent introduction of Web-based project coordination, a supposed panacea for the glitches in fast-track projects, does not necessarily reduce the time spent passing information back and forth. What’s more, the website calls for constant monitoring, even further increasing the mandate of instant response.

Who’s Left Holding the Ball?

All this dashing about and juggling projects ups the chances that something will go wrong. We know it, our clients probably know it as well. Yet we are expected to assume future liability for delays and their resultant costs. Remembering the slow times, we accept these conditions. Ever nervous, we resort to obsessive documentation, another drain on our time.

While the current AIA standard form contracts already load on the liability by making us the owner’s agent, they carry no provisions for the added exposure that comes from fast-tracking. It is vastly unfair that architects should bear the burden of such increased danger without exponentially increased compensation or sharing of liability.

What About the Architecture?

Hyper-connected, fast-tracked, paranoically documented: when is there the time and energy for the thoughtful contemplation and making of the work itself? When we do have some moments at the end of the day, we are exhausted and in a verbal rather than visual mode of thinking. A glance at the project schedule and budget tells us there are no billable hours left in the “design” column. Yet it is exactly the love of designing buildings that brought us to this profession in the first place.

As everyone zooms around, super cool because they have the tiniest cell phone or slickest modem device connecting them to the office, we have to wonder what the real Future is. How much more can we take on? How much more plugged in can we be? How much (more?) will the quality of work suffer as a result of the push for faster?

Author Lisa Findley, AIA, is a contributor to Architecture and Architectural Record and teaches in the School of Architecture at the California College of Arts and Crafts.

Photos by Luis Delgado.

Originally published in early 2000, in arcCA 00.1, “Zoning Time.”